New York City lost a living legend on Christmas Day, 2025, when the underground filmmaker Amos Poe departed this plane after a multi-year battle with colon cancer. Long before the obituaries, Poe was routinely cited as a “groundbreaking” or “pioneering” filmmaker from a movement called “No Wave Cinema,” associated with the contemporaneous music scene that solidified in Tribeca and the Lower East Side in the mid-1970s. In both music and film, No Wave was a rejection of norms. The surviving artworks testify to that moment’s energy: scuzzy, mischievous, nihilistic and postmodern on a low-to-no-budget. Poe’s biggest claims to fame were the 1976 rock anti-documentary The Blank Generation (co-directed with Patti Smith Group bassist Ivan Král) and, that same year, a remake/remodel of Breathless called Unmade Beds starring downtown fixture Duncan Hannah as “Rico,” a dashing yet abrasive American takeoff on Jean-Paul Belmondo whose original character in Breathless, of course, had been constructed by Godard as a crude xerox of Humphrey Bogart.

All January, Metrograph is hosting a series that situates Poe’s early work alongside more readily available titles like Bette Gordon’s Variety (1983), Susan Seidelman’s Smithereens (1982), and Edo Bertoglio’s Downtown ‘81 (1981/2000). The program includes my personal favorite of Poe’s movies, 1978’s The Foreigner, a deadpan spoof of the tropes of 1950s and ‘60s spy/detective television starring the French expatriate Eric Mitchell as a bleached-blonde secret agent called “Max Menace.” Little is known about Max, other than that he’s on an assignment from somewhere, waiting to be contacted by someone. Until that happens, he’s adrift in the alienating macropolis of Koch-era NYC, and Poe blends stunning locations (the newly-minted World Trade Center towers, Battery Park in its “hipster landfill” era) with queasy-making scenes of downtrodden bohemians screaming at each other in dingy, claustrophobic tenements.

Already posited as a genre exercise in negative space, The Foreigner loses narrative urgency and crumbles into the void while you’re watching it, like a tape that wears out taking its final spin. Upon its premiere at the Whitney Museum as part of the “New American Filmmakers” series, The New York Times critic Tom Buckley wrote:

No one in the cast, which includes a couple of comely young women, has the least idea of how to act, the story is infantile and the photography, sound and editing are primitive in a way that stopped being amusing 10 years ago…. It seems Incredible [sic] that a museum that is exhibiting Saul Steinberg on the third floor should be showing the cinematic equivalent of kindergarten scribbles on the second.

This is especially funny given that Poe would write, in an Instagram post about his very first short film: “Screened at the Millennium Film Workshop, another structuralist filmmaker mumbled it’s like a dysfunctional dyslexic 5 year old’s version of a Tarkovsky dream. I took it as a compliment.” This is the rub with No Wave: for all the in-hindsight romanticism ceded to the years of CBGB, Danceteria, and the Mudd Club, the easy affordability of art supplies and loft apartments (to say nothing of drugs) in the “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD” era, most of these artworks have retained their hardcore formal belligerence. As a document of Television, Richard Hell and the Voidoids, Blondie, Talking Heads and many others, The Blank Generation would probably be more famous if not for its gnashing, obstinate mismatching of image and sound, allegedly edited by Poe and Král in a strung-out, 24-hour blitz.

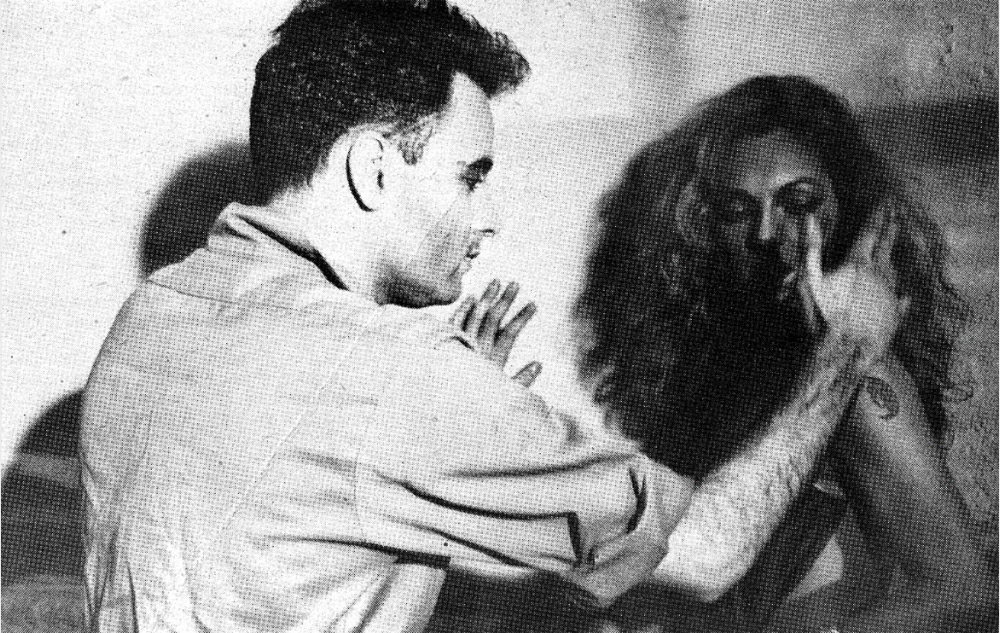

The Metrograph series also includes Subway Riders (1981, pictured at top, in a still with Poe and Cookie Mueller), Poe’s first film in color, starring John Lurie as a saxophonist-cum-serial killer; at least, that was the plan before Lurie—in whom Poe saw a kinship with Peter Lorre’s child-murderer in M (1931)—dropped out and Poe decided to cast himself as the lead to salvage the production, a decision he later characterized in a BOMB interview with Joel Rose as “against my better judgment.” The whole discussion is worth reading; Poe concedes that “The Foreigner remains a mystery to me” and goes on to say, “After shooting a film, everyone goes into a coma or a deep depression or both. There’s almost nothing as satisfying as the production period—it’s crazy and it’s when I feel most alive.”

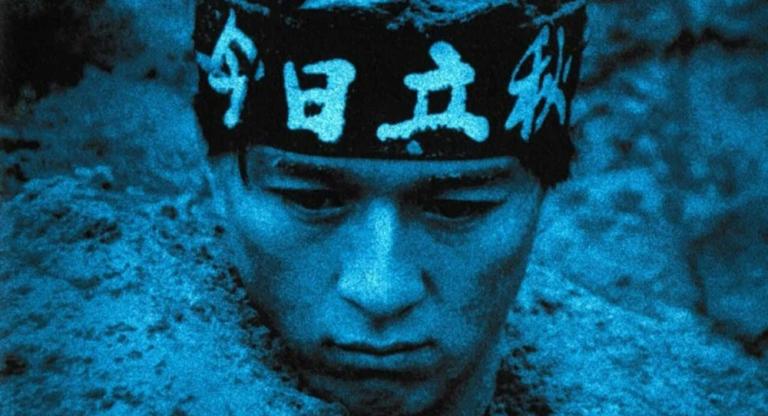

Like David Salle, Robert Longo, or Cindy Sherman, Poe executed a not-fully-successful pivot from the New York art world to Hollywood. His 1984 neo-noir thriller Alphabet City is stunningly slick compared to his earlier works, described by the filmmaker at a 2021 Nitehawk Q+A as an earnest attempt to remake The Battle of Algiers with “junkies and NYPD instead of freedom fighters and French paratroopers.” Featuring a drug bust sequence rendered entirely with blinding lights against Nile Rodgers’ score, the film manages to be all surface while utterly harrowing. Poe wrote (and doctored) many spec scripts. Only one got made: Rocket Gibraltar (1988), starring Burt Lancaster as a blacklisted screenwriter and Macauley Culkin as his grandson. (Poe took ownership of the fact that he was fired as director two weeks into production.) La Pacifica, an epic noir western script co-written with Joel Rose that caught the attention of Bruce Willis, blew up on the tarmac after a regime change at Warner Brothers, but lives on as a searing three-part graphic novel illustrated by the great Tayyar Ozkan.

Improbably, Metrograph’s series is Poe’s first-ever retrospective in New York City (if not the world), albeit an incomplete one. Rather than glistening digital restorations (à la Smithereens, Variety, or Downtown ‘81), Poe’s No Wave films are screening off of digibeta copies from his personal storage/archives. This is happening because Poe was legally forbidden for many years from showing, distributing, or profiting off of his films after Ivan Král (successfully) sued him on charges of withholding proceeds from The Blank Generation, on which he had co-director credit. The judge awarded Král ownership rights to several of Poe’s solo-credited films for $10 apiece. The story broke in an extensive New York Times feature published just a few months after Král’s death in 2020. The way Poe described this situation—which, for example, prohibited his films from being included in the Museum of Modern Art’s 2017 “Club 57” exhibition—to me was, “Ivan Král threatened to sue Iggy Pop, Patti Smith and myself. Iggy and Patti lawyered up and figured it out; I called ‘bullshit’ and paid the price.”

Poe went up against a breathtaking variety of setbacks and adversities, but he never stopped creating. The Metrograph series includes Empire II (2007), his brain-breaking, three-hour reworking of Warhol’s structuralist classic, focused entirely on and around the Empire State Building as viewed from Poe’s window in MiniDV. This film was also long-unavailable after the judge awarded its ownership to Král, despite the fact that Poe made it some 30+ years after their last collaboration. It seems possible that the bad publicity in 2020 played a role in Král’s estate easing up on Poe, who was able to attend a handful of Metrograph and Roxy screenings before his cancer diagnosis. He leaves behind an utterly unique, righteously challenging body of work younger generations can (now) begin to appreciate. That his signature works can be seen on the big screen is a miracle, albeit one that has arrived just a moment too late—but, this feels like yet another cruel irony Amos Poe would have appreciated.

Empire II and The Foreigner screen tonight, January 10, at Metrograph as part of the series “Amos Poe and No Wave Cinema,” which runs until January 24. Author Vera Dika will introduce the former.