It’s inapt to call Something’s Gotta Give Nancy Meyers’s masterpiece, because she is—miraculously, improbably—beginning production on a new film, slated for release in December 2027. And, as Sinatra’s tombstone used to read, the best is yet to come. Meyers’s first solo directing credit, The Parent Trap (1998), is a different masterpiece, one that could only have come into existence fraught with the expectations and caveats that accompany any Walt Disney Company product, let alone an audacious reimagining of a first-blush classic like the 1961 original. Meyers fully understood the assignment, and her Parent Trap represented a new beginning because it had originated as a collaboration with her now ex-husband, the late Charles Sheyer. What Women Want (2000) came next, a mega-hit that consecrated Meyers as the most profitable female director of all time (shattering Mimi Leder’s record with Deep Impact, 1998). And yet that project had its own tortured history, initially picked up and plopped into turnaround as a spec script for Tim Allen titled Head Games. Watching the finished thing, the oppressive influence of its lead, Mel Gibson, feels inextricable from the whole. So approaching Something’s Gotta Give means entering Meyers’s world for the first time: no copilot or co-writer, no star-as-auteur, no intellectual property or looming precedent. Yet, as it turns out, looming precedent is the whole problem.

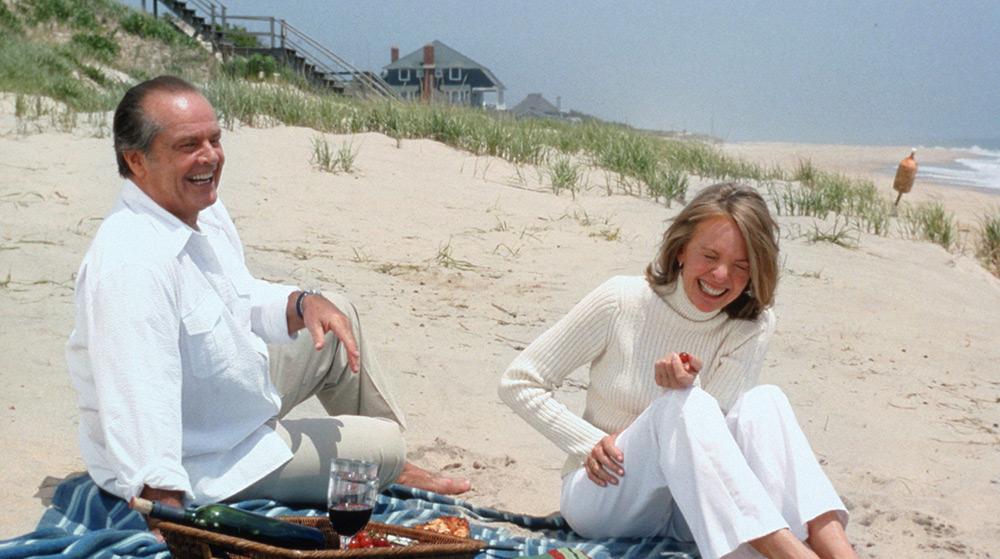

Jack Nicholson stars as a music executive named Harry (founder of “Drive-By Records”) whose heretofore experience of women is what you might expect for a 20th century titan of industry: all work, much play, and never any strings attached. Harry retreats to the Hamptons for a summer getaway with his significantly younger girlfriend Marin (Amanda Peet), with whom he has not yet consummated his relationship and we learn that Marin failed to tell her mother, a celebrated playwright named Erica (Diane Keaton), about her plans to use the vacation home that weekend; Erica was planning on doing the same in order to break her latest bout of writer’s block. Harry suffers a heart attack before he and Marin can get anywhere near flagrante delicto, obliging him to shelter in place; Erica, her sister Zoe (Frances McDormand), and Marin form a coven around him which, to Erica’s consternation, distracts from her original plan. Things are further complicated by Harry’s dreamboat cardiologist Julian (Keanu Reeves), who, it turns out, has read or seen every one of Erica’s plays.

This setup might as well have come from the Restoration comedies of the 17th century, but it’s also a wholly modern reflection on Meyers’s long career in showbiz. She constructed Something’s Gotta Give as a deliberate vehicle for Keaton and Nicholson, an exercise in challenging and complicating their established iconic personae; Meyers described the movie to Charlie Rose (a different irredeemable codger) as being about “finding out that you don’t have to be the person you’re convinced that you are,” elaborating that “you write yourself off, in a way: This is who I am.” No surprise Erica and Harry can’t stand each other upon first meeting. Much is made of Erica’s painstaking, anal-retentive, “flinty” and “impervious” personality, while his “ultimate bachelor” reputation disguises a soulfulness that Erica eventually becomes obsessed with. Her plays are exclusively directed by her ex-husband and unabashedly cut from the cloth of her most recent life experiences, which gives Meyers’s comedy a dark undercurrent of cynicism about just how limited an artist’s options are to truly escape (or exorcise) real-life disappointments with their work.

Something’s Gotta Give establishes givens up-front before dissecting the expectations of all parties with scalpel-like precision, including the audience’s. Harry’s redemption narrative is rooted in a depiction of haute-elite male lecherousness that looks positively quaint in an era of Epsteins and Combses. The love triangle between Harry, Erica and Julian becomes a pretty obvious fait accompli, not unlike the one between Meryl Streep, Alec Baldwin, and Steve Martin in It’s Complicated (2009), or Anne Hathaway, her husband (Anders Holm), and her girlboss CEO job in The Intern (2015). Keaton’s signature gee-whiz awkwardness gives way to a deeper meditation on existential anomie: when Erica does find inspiration, it comes from a deep-seated fear of having become fully unlovable in her middle age. (In one of the most celebrated sequences in Meyers’s career, Erica’s cathartic, weeks-long writing marathon is fueled by hysterical tears that make spots on her Macbook keyboard.) Like much else in this story of rich boomers exposing themselves to one another in unflattering light, it’s opulent and ludicrous, and breathtakingly out-of-sync with the workaday concerns of real people. But maybe the gilded unreality is the point. Something’s Gotta Give is not just about falling in love, but about discovering freedom even when you thought you had already reached the summit of life—startled to learn there’s still time to change, whipsawed by the jarring realization your life is not yet over.

Something’s Gotta Give screens tonight, February 14, and on February 19, at Film at Lincoln Center as part of the series “Looking for Mrs. Keaton.”