Since the last time I visited Toronto, in 2019, the view from my friends’ Parkdale apartment has changed completely. The city is in the midst of a massive development wave, coinciding with a massive housing crisis. Brand-new luxury towers loom over tent encampments whose inhabitants must soon brace for winter. “A change is proposed for this site” signage abounds, denoting planned demolitions. Even the Scotiabank Theatre, where I spent much of my time while in town, is on the chopping block, never mind the architectural significance of its turn-of-the-century Rubik’s cube cornice. Appropriately or otherwise, the brand identity for the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival is all colorful skyscrapers, the distinctive shadow of the CN Tower falling atop one of them.

As I sat down for the first film I would see, I received news of Queen Elizabeth II’s death. I usually have no reason to think or feel anything about the House of Windsor, but I had just seen its matriarch on the crisp polymer $20 bills coming out of the ATM as I changed currency. I had forgotten I was in the Commonwealth. Within days, her face was everywhere: on TTC subway screens, on CP24’s delightfully bizarre split-screen news broadcasts, even on a t-shirt for sale at a discount store on Spadina Avenue, the main artery of Toronto’s Chinatown. When Jean-Luc Godard ended his life five days later, I and many others experienced some approximation of that grief evinced by those for whom the Queen’s work had meant so much.

That first film was Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica (all films 2022), one of two projects in the festival to have emerged from the loose affiliation of resources and affinities that is Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab. Likening the pneumatic messaging systems and graffitied back hallways of French hospitals to their patients’ lower intestines and prostates, the documentary conducts a stunning visual and aural study of the ailing human body and its caretakers, by turns Sisyphus and Dionysus. Like any good medical film, this one revels in transforming abstraction to actuality; the surreal landscape of viscera is often broken by the appearance of a hard-edged implement, sharp and terrible, which intrudes upon the scene in order to provide some mysterious (but always material) remedy. Through the thrum of a patient’s heartbeat, the arguments, instructions, and idle chatter of the attendants can be clearly heard.

Joana Pimenta and Adirley Quéiros’s Dry Ground Burning is also affiliated with the Sensory Ethnography Lab. In the fictional passages of the hybrid documentary, a small band of women have bought a piece of land on top of an oil pipeline in Brasília’s Sol Nascente favela. They are illicitly extracting some of its contents and refining that oil into gasoline, which they sell to motorbike delivery workers. One of them is running for district deputy against the Bolsonsaro-backed police superintendent on a platform of ending the nightly curfew and investing in infrastructure, schools, and hospitals to accompany the prison around which much of the area’s economic and social life revolve. The plot unravels slowly and non-linearly, partly in song: hymns, ballads, rap, and political sloganeering are adjoined by quiet conversations and reminiscences. The film insists, seemingly for the sake of strained metaphor, on having its characters light up a cigarette in every scene, to the point of tedium. Still, it becomes easier to forgive some clumsy artifice when the existential stakes for its performers are made clear in the final minutes.

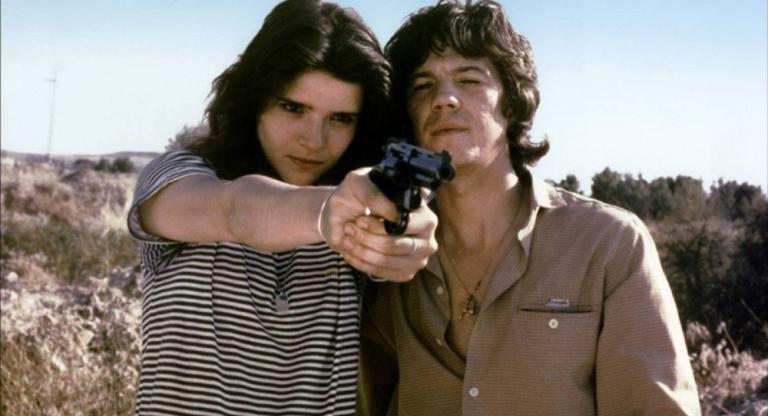

Another film deals with resistance to fossil capitalism in a very different way, with ideological sabotage in place of subsistence-level profiteering. How to Blow Up a Pipeline, directed by Daniel Goldhaber and co-written by star Ariela Barer and Duke University scholar Jordan Sjol,, is among the critical darlings to emerge from the festival. Some are falling over themselves to commend the thrilling simplicity and stridency of its bank-heist plot, transposed to a piece of energy infrastructure in west Texas. Others deride the film for the same reasons. It is based on Andreas Malm’s nonfiction book of the same name, an argument for expanding the sights of environmental activism beyond the polite and peaceful, justifying the righteousness of violence with the urgency of the climate crisis. All the same, the movie takes pains to emphasize that no one need be hurt in the making of this blown-up pipeline.

Consciously—but perhaps not carefully enough—this all-American agitprop assigns archetypal roles to its characters: the academic, the filmmaker, the libertarian, the loner, the sick one, the skeptic, the punks. In addition to their responsibilities to the bombing plot, they each serve to represent a certain tendency in the eco-activist milieu, the cooperation of which will be essential to success of any revolutionary project, the film suggests. These representations are uniformly flat, and for a film based on a manifesto you’d think the language might be more persuasive. Still, the potential for the dissemination of its ideas is far greater than would be the case for a more complex movie. The bluntness of its statement is certainly more Costa-Gavras than Godard, though its actual commitments can’t quite be discerned through the warm fuzzies of its happy ending. The film’s mid-fest acquisition by NEON ensures it will be relatively widely seen. Whether it can be an effective messenger for its radical provocation, and not just a feel-cool bias-confirmation flick, only time will tell.

The winner of the TIFF people’s choice award was Steven Spielberg’s The Fablemans, a rip-roaring film that plays like a celebrity memoir ghost-written by a real wit with a taste for the literal (in this case, Tony Kushner). Michelle Williams and Paul Dano are terrific as the heads of household presiding over a slow-motion trainwreck. Her going-to-pieces performance renders mania and despair as convincingly as one’s own mother might, carrying the character very far along from what she must have been on the page. Dano is sublimely ineffectual, his voice cracking at the edge of its range and fraying into that resonant hum which is his trademark—just enough, not too much. The scenes in which the young director, Sam (ably played by newcomer Gabe LaBelle), confronts the evidentiary quality of his medium are silly when they shouldn’t be, but Williams ennobles the discovery of her infidelity in a way that still moves me to think about now.

Later, Sam encounters believably cornball antisemitism in high school and conquers his bully by making him a hero, a beat that doesn’t go over nearly so well, since neither of the actors seem to understand what is happening in that scene. Nearby is Chloe East as an enchanting Jesus fanatic; the whole tone of the film must change to incorporate her huge performance (just as it accommodated Judd Hirsch, half an hour earlier), and good thing it does. In all, the film is the best thing it could possibly be: a big-hearted blockbuster with laughs, tears, and winking fan service for the whole family. It feels strange to be piling more praise onto the auto-hagiography of the world’s most successful living purveyor of moving images, but there it is.

And then there were the films suddenly pulled from the slate: Vera Drew’s The People’s Joker, which screened only once before being pulled by the filmmaker due to copyright concerns, and Ulrich Seidl’s Sparta, which never premiered after far more serious charges emerged of the endangerment of child actors (a subject covered in another selection, Lise Akoka and Romane Gueret’s The Worst Ones.)

Under separate cover, I wrote about Until Branches Bend, a wit’s-end, dual-urgency narrative set in the peach orchards of British Columbia's Okanagan region. Meanwhile, the tireless Mark Asch reviewed Joanna Hogg’s The Eternal Daughter, Alice Diop’s Saint Omer, Sarah Polley’s Women Talking, Stéphane Lafleur’s Viking, and Sébastien Lifshitz’s Casa Susanna.

Stay tuned for our coverage of the New York Film Festival, running September 30–October 16 at Film at Lincoln Center, where some of these films—and many more—will play.