The Belgian poet and experimental filmmaker Marcel Broodthaers’s turn toward visual art at age 40 was less a pivot than a deepening of his existing impulses. Symbolist poetry and its slippery, associative approach to language (Broodthaers’s forte) would become fertile soil for the study of images, resignified constantly in his late-career film practice. Broodthaers, the great “assemblagist,” tended toward fixed images paired with intertitles, sometimes recreating the sensation of flipping through a book about art. In his Ceci Ne Serait Pas Une Pipe (1970) and A Voyage on the North Sea (1974), images of paintings are repeated with accompanying numbers—an index of existing artworks recoded into a “moving image.”

Shot between the two general elections in the United Kingdom in 1974, Broodthaers’s 16-minute film Figures of Wax leans (auto)biographical, depicting the director in conversation with the preserved skeleton and wax head of the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham. The film opens with scenes of London: hordes of double-decker buses, newspaper stands, a corner shop on the brink of closure, and, pointedly, just before cutting to Bentham’s waxy visage, a row of mannequins wearing exaggerated makeup. Cordoned off by a vitrine in University College London, the famed founder of utilitarianism sits clothed in a chair, while voice-over details his life’s work.

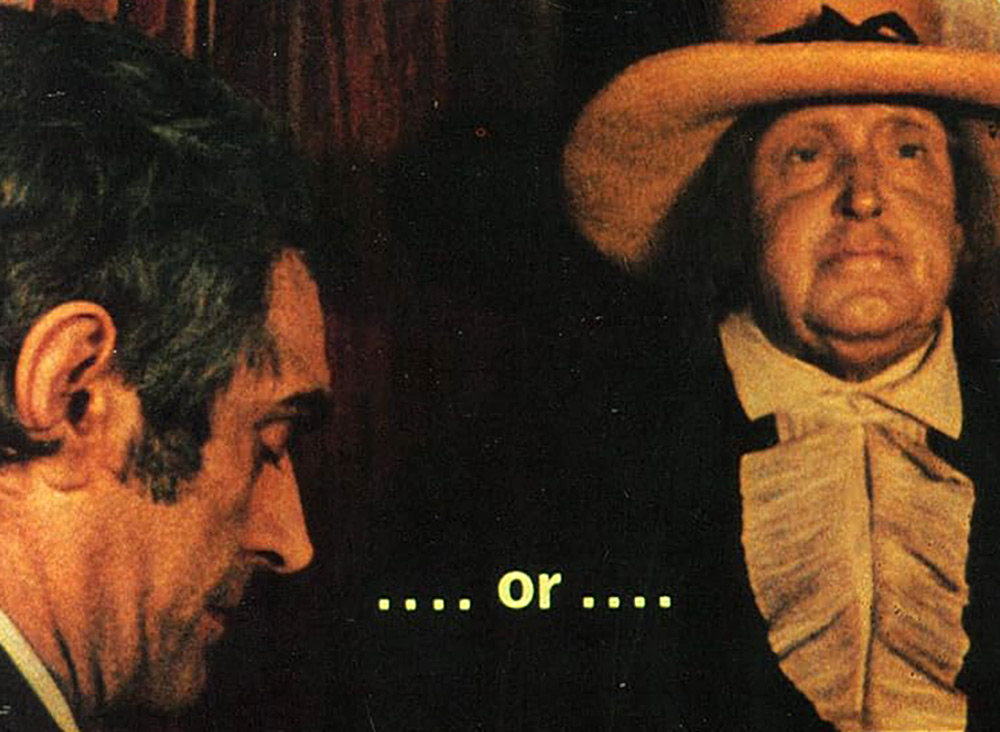

The narrator invokes Bentham’s pamphlet Auto-Icon, or, Farther Uses of the Dead to the Living, in which he advocates for the mummified display of such “auto-icons” as himself, created for the dual purpose of desensitizing death and eliminating the need for fine art. In Bentham’s view, where paintings and statues only aspire to human likeness, the auto-icon necessitates it. (“Is not identity preferable to similitude?” he writes.) Running underneath this narration, like a tremor, are subtitles which communicate Broodthaers’s mouthed monologue as he sits outside of the glass, begging for engagement: “If you have a secret / tell me / or a special message / give an indication. / If you wish to protest. / I promise to keep it / … Or … / you prefer to dream?”

More confounding than the man who had himself taxidermied is the man who attempts to withdraw the cobbled corpse’s spirit years later. Even the rich canon of wax-horror cinema—House of Wax (1953/2005), Waxwork (1988), Nightmare in Wax (1969), Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933)—could not conceive such a necromantic plot. Fittingly, Broodthaers had previously moderated an imaginary interview with René Magritte in 1967.

Broodthaers uses safeguarded images (humanoid objects behind glass) to enact a critique of commodity fetishism at a moment of economic collapse in the U.K. If his previous films felt like reading a book or placard, Figures of Wax emulates both window shopping and an operating theater. A dissection takes place at the level of editing: close-ups on skin folds, wrinkles in clothing, gloves, shoes. Pulled apart by the camera, Bentham is an incomplete subject, stunted by the film’s form which, through simple cuts to everyday objects, flattens his likeness. As art historian Steven Jacobs puts it in his 2024 book on Broodthaers, Bentham “became his own image—a fact that must have appealed to Broodthaers as Bentham became an imprint or a cast of himself, like a mussel and a mold… and foremost an index.”

CONTOURS is a column by Saffron Maeve (and guests) examining films that thematize the world of visual art: painting, sculpture, illustration, and performance. Maeve also programs a screening series of the same name and premise at Paradise Theatre in Toronto.

Figures of Wax screens this evening, July 11, at Anthology Film Archives on 16mm as part of “Marcel Broodthaers: Rendez-Vous Mit Jacques Offenbach & Other Films.”