Throughout his 60-year career, the prolific Bengali director Mrinal Sen captured the social and political struggles of his time on film. His life’s work, dedicated to representing daily life in post-Partition India, defied mainstream cinema, creatively circumventing state-censorship and playing with the possibilities of the medium. His political satire, Bhuvan Shome (1969), adapted from Balai Chand Mukhopadhyay’s tongue-and-cheek novel Banaphool, played a major role in ushering forth the period of artistic experimentation that characterized the foundational years of India’s New Cinema Movement. Screening as part of Asia Society’s new series, “Parallel Days/Bollywood Nights,” the film delivers a layered, flippant portrayal of Bhuvan Shome (Utpal Dutt), a strict and newly-widowed railway officer who takes up bird-hunting in 1940s India.

The film opens in the ballast of the train tracks, facing down as a train passes at feverishly high speed. Nervous improvisational drums and cymbals crash, juxtaposed with classical Indian raga music. This train carries the uptight bureaucrat Bhuvan Shome. We first hear about him through his employees’ gossip, who are anticipating the arrival of their boss. “Let's see what scene he creates.” This teasing endures throughout. Beyond the walls of his office, Shome is subject to all kinds of characters and situations in the Indian countryside that uproot his behavior. Sen plots Shome’s journey to the state of Gujarat in unrest, punishing the bureaucrat from the start. He places him in the back of a speeding oxen cart, subject to tremors that recall those of the trains he supervises; the audio-visual motif, in turn, doubles as a representation of the differences between pre- and post-partition India.

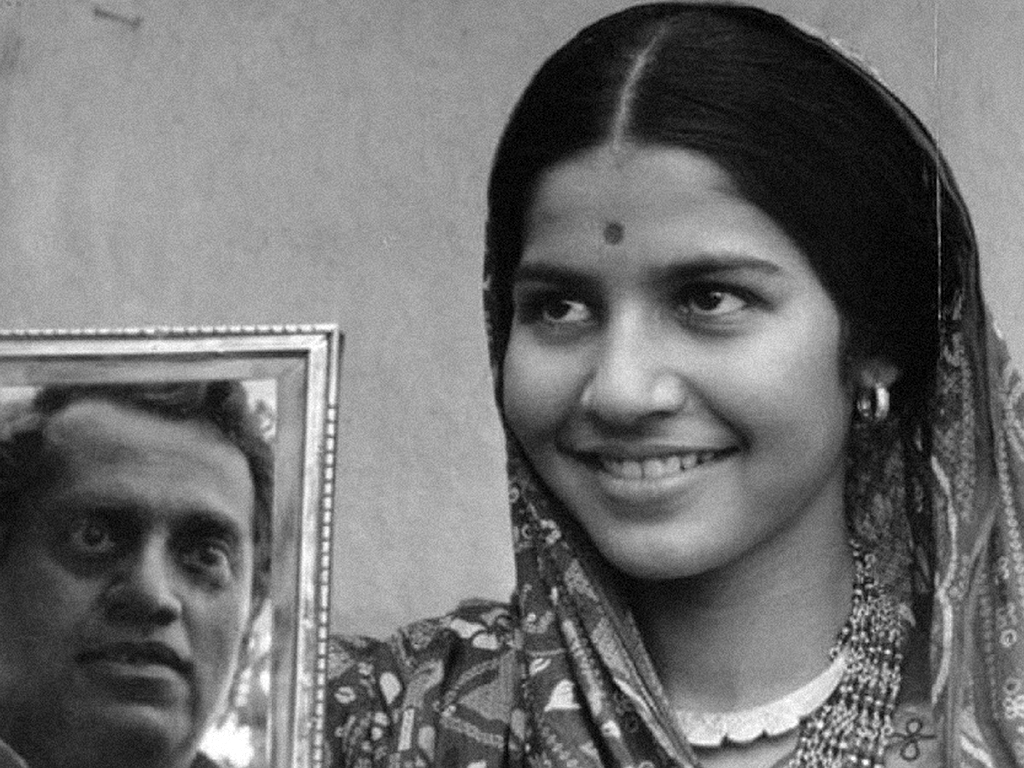

But the spectacular charm of Bhuvan Shome lies in Suhasini Mulay’s brilliant performance as Gauri, who appears about 30 minutes into the film. The film is animated by her charisma. She provides an enchanting force that interrupts Shome’s aimless and chaotic journey. Their relationship, in which his bourgeois naïveté and clumsiness juxtapose with her graceful and nimble movements, is charming, like that of a playful, unspoken crush between classmates. Under the pretense that she is guiding him in his hunt, Guari begins to develop a relationship with Shome through a series of intimate acts: she prepares a meal for him and her father; they tend to an injured bird; they repeatedly gaze at murmuring birds. Gauri brings Shome further into his interior, confronting him with the fact that his true desires are not within his reach. When the pair encounter flying birds, Sen keeps the two off-screen and instead focuses his camera on the flocks. These scenes are arrestingly beautiful, as if mirroring the transcendence of their brief and poignant relationship.

Sen uses his camera to play subtle ruses; although seemingly straightforward, Bhuvan Shome is as complex as the subject matter it takes on. Embedded in the film is the possibility of self-discovery and a new social order, however fleeting it might be. This becomes clear in Sen’s use of footage from Calcutta's Naxalite uprisings, which anchors the film in class tensions and post-independence national pride. (Sen is also known for militant experimental films, such as 1973’s The Guerilla Fighter.) As a filmmaker, Sen resists dealing in narratives of major progression, instead emphasizing the tension in stories that focus on matters of becoming. In the end, Shome is left alone in his office. This time, he is reclining across his desk, tossing documents in the air as though they were confetti. Swirling about his office and transforming it into a site of play, Shome confronts his own transformation finding a temporary escape from the confines of his bureaucratic lifestyle.

Bhuvan Shome screens this afternoon, July 12, at Asia Society as part of the series “Parallel Days/Bollywood Nights.” It will be introduced by Mrinal Sen’s son, Kunal.