Each fall Screen Slate is pleased to offer writers' candid takes on many of the noteworthy films in the New York Film Festival line-up – no "must see films," no hype.

Although we intend to focus our coverage on the Main Slate, we'll also chime in on the Spotlight on Documentary and Projections line-ups as availability allows and will incorporate Revivals and Retrospectives into our usual stream of daily featured screenings.

This article will be updated throughout the festival, to be noted on our daily email and social media. And if you have difficulty sorting through ticket prices, online queues, rushes, sellouts, and standby lines, you can consult the Film Society's website for ticket information and an updated list of availability. Of course, many of the films have distribution (as noted below), so if you miss out on anything, there's a good chance it's coming to a theater near you.

ASAKO I & II

Dir. Ryusuke Hamaguchi. 119 min.

U.S. Premire. A Grasshopper Films release.

Director Ryusuke Hamaguchi has followed his intimate, five-hour Happy Hour with this film of small miracles. It is hard, at first, to parse Asako I & II. Characters date, part, act, reconnect, throw successful or unsuccessful dinner parties, advance at work, move house. Viewers mulling over the title may await, as in Vertigo or The Double Life of Veronique, the calm-faced Asako's (Erika Karata) second self to emerge and disturb a narrative as surface-smooth as new ice. Underscoring this bait and switch is her visit, in the film's first minutes, to an Osaka exhibit of Shigeo Gochō photos. One snares her special attention: an image of twin girls in matching frocks. Does Asako know this double, or does she see herself in the doubling?

Matters are muddled further when, while there, she encounters Baku (Masahiro Higashide), a shuffling, mop-haired twentysomething who is her opposite—so of course they fall in love. The pair's first kiss, staged in syrupy slow-motion as crouched children spark fireworks around them, is one of Asako I & II's frequent, winking gestures to the fantastical. Others abound. A motorcycle crash appears fatal until the riders roll away unscathed. An earthquake that downs a chandelier and plunges a theater into darkness becomes the backdrop for a chance meeting. A coiffed man dressed in white enters wordlessly and rests his open palm on a table. Of his trip to the Northern Lights, he murmurs that the sky and the sea seemed one, a potential metaphor for this film's intertwining of the real and the surreal.

Hamaguchi buries the miraculous under the banal, and vice versa, tracking his characters through cafés and conference rooms, cramped apartments and ordinary streets, with the wide-eyed sincerity of melodrama. When Asako chances across "Baku" again, as Ryohei (also Masahiro Higashide), a straitlaced salesman for a sake company, she is doing nothing more than retrieving a coffee urn for her shop next door. Fate can feel banal to the people it most entangles. Or is it happenstance? Hamaguchi blurs the mundane and the mysterious to suggest there is no difference between the two. For Asako, there is only a single choice. (Courtney Duckworth)

ASH IS PUREST WHITE

Dir. Jia Zhang-ke. 141 min.

U.S. Premiere. A Cohen Media Group release.

Jia's latest traces a circular, broken path around China at the peak of its rapid development, following Qiao, gutsy girlfriend of mid-level gangster Bin, as she tries to catch up in a world that left her far behind. She starts secure amid insecurity in 2001, commuting from her dying coal town to Bin's successful gambling den, known and mostly respected but unable to get her father out of public housing, despite Bin's boss working a crooked construction operation. It's the first hint of Bin's real feelings towards her - actions speak louder than words and for all Bin's bluster about being part of the jianghu (a brotherhood of outsiders with skills instead of rank), it's Qiao who acts and adapts. She's even the one to toast with their crew's "Five Lakes and Four Oceans" jungle juice, also the name of a jianghu handshake symbolizing equality among men throughout the vast domain of China.

Bin's boss is suddenly taken out, making Bin the focus of rival gang attention. The Killer is a touchstone; once when the entire gang watches it slack-jawed on TV, and again as stylistic reference for the film's hinge point - a tense two-shot action scene where a whim of distant dumplings (anything is possible in this grand age) turns into a crisis point. Qiao takes action and later, the blame, spending five years in prison. Around her everything is moving at a pace so breakneck negative repercussions lag like a sonic boom, and even incarcerated she's not immune - finally tearing down her old, outdated prison also means she's relocated to a remote location, definitively precluding visitors, including Bin, that never came.

Five years later she's out and determined to talk to Bin in person. She glides through the Three Gorges as a guide notes which sections will soon be underwater. Scammed on the tour boat out of what little she had, Qiao begins the tempering hinted at in the title - that which burns hottest becomes purest. Rolling with the situation she begins scamming others herself, doing whatever it takes to confront Bin directly.

This being the sole Jia I've seen, I can't speak to how this film treads back over his own mapped territory - others have said it better elsewhere. He did say living in China the last decade is a surreal experience, change on a scale so far beyond human it must have superhuman origin. So when Qiao finds herself in the hinterlands in the middle of the night, leaving behind an opportunity to align her identity with yet another mediocre man, should we be surprised she sees a UFO? At her furthest, in a place where modernity's barely touched, futurism is already there waiting. She circles back, but the future catches up with her even as she re-mires herself in her past. Security cameras bring modern tech to the old gambling den, a monitor in her apartment letting her see everything except Bin leaving on New Year's Day 2018, the present finally catching up. It's like The Giving Tree of gangster films: Qiao keeps sacrificing out of duty and Bin keeps taking without thinking; but even at the end of that horrible book the man sat on the stump - here, the moment Bin recovers he walks away, leaving Qiao as she always was - sure but uncertain. (Danielle Burgos at TIFF)

AT ETERNITY'S GATE

Dir. Julian Schnabel. 111 min.

North American Premiere. A CBS Films release.

The newest entry in Julian Schnabel's ongoing series of films about artists better than Julian Schnabel is set during more or less the same period as Maurice Pialat's superior Van Gogh. Which is helpful for the purposes of comparison, if not for my blood pressure. Whereas Pialat's patient, devastating end-of-life biography focuses on the life surrounding Van Gogh's dying art—his paintings functioning almost like ecstatic doodles in the margins of a Zola novel about the never-ending hassles in a disturbed life—Schnabel, pajama-clad Ahab that he is, dives bravely into the Artist's Mind by employing Rubber Band Man handheld photography and having more than one character ask Vincent, "Why do you paint?"

The handheld work is energetic and attractive but, as a work of visual psychology, it's a little bogus: Terry Gilliam by way of a hummingbird. On top of that, many sequences are shot through a split diopter, making the bottom third of the screen a smudge. It's an neat technique if you don't think about it for more than a few seconds. (Did Van Gogh need bifocals? Was this the source of his torment?) The experience of watching the film—lots of cuts to black, disorienting dialogue loops, one POV shot after another, a sentimental piano score that sounds like it was ripped from one of those "Intense Studying" playlists on Spotify—suggests a film school thesis on techniques in fragmentation. Which isn't a sin in itself, but the fragments don't really accumulate. The arty stops and starts just lead to monotony. The film's disorganized, and not in a good way.

Dafoe, ever the indelible presence, looks the part, even if he's a quarter-century older than Van Gogh was when he died. His sunken cheeks and split eyeballs are used heavily and well—he looks like a Van Gogh painting of Van Gogh. But his performance is off. Schnabel dedicates much screen time to scenes of Vincent wandering the countryside—the olive trees! the sunflowers!—and digging the nature vibes like a touched fool. The portrayal is open, generous, at times almost beatific. (One short interlude has Vincent swaying in grain, hands turned up, a giant smile on his face. The idea falls somewhere between Malick and Woodstock, and it's very silly.)

Dafoe's Van Gogh, when he isn't having one of his tortured episodes, is unaccountably legible. He's an open-book kind of guy, with smiles aplenty, placidly thoughtful, dangerous only when he roughs up a school kid or cuts off an ear. (This very famous episode is dealt with during a lengthy post-mortem psychiatric consultation, maybe because Schnabel feels more comfortable figuring the artist out through the puzzled questions of a psychiatrist or priest. Not coincidentally, the psychiatrist and priest scenes the strongest in the film.) Insanity comes on in isolated sequences, then disappears as soon as, say, Vincent's loving brother Theo steps in the room. Schnabel, content to have his characters bloviate on Van Gogh's eternal reach, fails utterly to capture the porousness of despair. (John Magary)

THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS

Dir. Joel & Ethan Cohen. 128 min.

North American Premiere. A Netflix release.

Being what amounts to a two hour regurgitation of dull Western stereotypes, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs offers little to recommend it. Framed as six "chapters" of unrelated set-pieces, we get Tim Blake Nelson as a singing, fourth-wall-breaking cowboy, and a cardboard James Franco playing a pitiable outlaw. Tom Waits, Bill Heck, and Zoe Kazan make the best of flimsy parts, while Liam Neeson and Harry Melling make the worst of theirs. Eventually it all ends with five people stuffed in a stage coach with a dead body on the roof—a skit which none of the actors seem to understand. Brendan Gleeson breaks in with a melancholy rendition of The Unfortunate Rake, but can only do his best to mourn the bad material.

Dismissing Scruggs as a failed experiment would be letting it off too easy. Its arbitrary tracking shots, careless use of depth and perspective, and CGI wildlife are aggravating enough. But it also peddles a backward kind of parody that doesn't seem to notice that all the Indians do is holler, scalp people and get shot; that all the Irish actors do is sing acapella versions of morbid barroom ballads; and that the few women involved are either whores, "pretty," or in distress.

As an homage to the worst Western clichés, Scruggs succeeds in creating a typology of what should readily be abandoned by a 21st-Century Western. Sadly, it'slikely to be lionized as good old-fashioned filmmaking—further burying a genre that, at its best, has been one of the few popular outlets for Americans to make art about two of their greatest obsessions: public vs. private morality and the vastness of the American landscape. (Jon Auman)

BORDER

Dir. Ali Abbasi. 110 min.

U.S. Premiere. A NEON release.

Ugliness takes on many forms, and one was audible audience discomfort with the physical appearance and sexuality of the main characters in Ali Abbasi's tale of cultural and personal repression. The film doesn't sugarcoat their neanderthal appearance or downplay any potential revulsion, but it's their patent difference that's the butt of the joke (when it's a joke); Abbasi never mocks them.

Border guard Tina is preternaturally great at her job, able to pick out smugglers and illicit goods that elude her fellow agents. Heavyset with thick facial features, she literally sniffs out emotions, particularly fear and guilt. She's reconciled herself to dull routine - sensing the occasional drugs, visiting her father, coming home to a neutered relationship with her dog-breeding obsessed boyfriend; her few pleasures communing with animals and natural tactility. Until one day, a traveller named Vore strangely resembling Tina walks through, eager to be examined. Tina can't get a read on him. Still unsettled and intrigued, she sniffs out child pornography on a clean-cut businessman's phone.

The two encounters change Tina's life, altering her perception of humanity and herself completely. Allegory for the trauma suffered by indigenous people stripped of identity, Tina's rage realizing the scope of what was taken from her and confrontation with horrors from her adopted culture are balanced by her growing relationship with Vore. The film's otherworldly elements never feel too fantastical, grounded by Eva Melander giving genuine heft to Tina's emotional journey as she grapples with a newfound identity outside the world she tried conforming to. (Danielle Burgos at TIFF)

BURNING

Dir. Lee Chang-dong. 148 min.

A Well Go USA release.

Shin Haemi (Jong-seo Jeon), in one of Burning's early scenes, shares her skill for pantomime with the dopy, slack-jawed Lee Jongsu (Yoo Ah-in), an alleged Paju acquaintance who she meets in Seoul as she prances in a miniskirt to promote a raffle. Haemi lures him with the rigged prize of a sports watch, but glimpsing her face, he draws a blank; "plastic surgery," she explains. That evening, in a golden-hued bar, she pinches her fingers together to simulate sucking on a tangerine. Haemi reveals that to pull off a pantomime she need not convince onlookers that the tangerine is real but to make them forget that it is not. Voids furnish their own meanings. Burning, as in pantomime, draws on viewers' hunger for substance, our willingness to infer a false reality in the face of intolerable gaps. Adapted from a Haruki Murakami story that itself echoes Faulkner's same-titled "Barn Burning," Lee Chang-dong's first film in eight years teases with denials and disappearances, murky characters and opaque subjectivities.

Haemi, her identity as dubious as her face, insinuates herself in Jongsu's life with prattling charm. The two fuck in her shoebox apartment beneath the glimmering spire of Seoul Tower, which Jongsu later eroticizes, and she thrusts on him the role of cat sitter when she skips off to Africa for a spiritual pilgrimage. She returns with the uncannily blithe Ben (Steven Yeun), a Porsche-driving idler with untraceable wealth who makes Jongsu, the wannabe-novelist son of a poor farmer imprisoned for his recurrent temper, feel ever the beta male. Now captivated by Haemi, the jilted Jongsu suspects Ben to be a Gangnam Gatsby: crafty, careless, violent. And the film, as if to affirm Jongsu's instincts and ours, accrues sinister signs: a yawn, a cosmetic case, a trinket drawer, a tale of a girl lost in a well, Haemi's cat that Jongsu never sees. Everything oversignifies. Could he—could we—be guilty of a misreading? Burning coaxes such convincing flames out of thin air that we can ignore how little we know of this ménage à trois. Fitzgerald's Gatsby is the one who wound up dead, after all, floating in cool water. (Courtney Duckworth)

DIAMANTINO

Dir. Gabriel Abrantes, Daniel Schmidt. 97 min.

U.S. Premiere. A Kino Lorber release.

Slapping together hot-button topics into a sub-Lubischian plot, this self-consciously zany movie squeaks by on charm. Diamantino is Portugal's star footballer, his professional edge his complete naivete – the film's finest moments show his point of view on the field, opposing players replaced by long-haired puppies romping in candy-pink fluff. While sunning on his yacht one weekend he encounters raft-bound refugees whose plight pops his innocent bubble, causing him to lose the World Cup and become an international laughingstock. From there it's a melange of lesbian government operatives, evil twin sisters, genetic modification and nationalism, as Diamanto's unwittingly embroiled in a scheme to Make Portugal Great Again through sports deification. Carlotto Cota's sweetly vapid performance sells a lot but can't quite make up for a paper-thin romance, and some of the CGI towards the end seems more mistake than stylistic choice. Still, despite including nearly every politicized issue of the day, the film never pretends a depth it doesn't have, making this ostentatiously oddball comedy enjoyable as a desktop folder full of puppy pictures. (Danielle Burgos at TIFF)

DIVIDE AND CONQUER: THE STORY OF ROGER AILES

Dir. Alexis Bloom. 107 min.

An A&E IndieFilms release.

Divide and Conquer: The Story of Roger Ailes does its best to be two things at once. It bills itself as a multi-faceted portrait of its subject—the disgraced Fox News executive, one time tap dancing enthusiast, and "Ernest Hemingway of campaign advisors." But what it wants to be is an unsparing exposé on Ailes's institutionalization of sexual abuse at Fox News.

Using the now ubiquitous (and mind numbing) format of talking heads, drone flyovers, and awkward reenactment footage, the film's first half walks us through the various stages of Ailes: the Eisenhower stumping, everybody-wants-to-be-me schoolboy; the pseudo-Machiavellian Mike Douglas Show producer; the man who made Richard Nixon palatable to television; and "Big Rog" the GOP's media fixer. The man we're shown doesn't quite add up to what one interviewee calls "a genius." But the bare facts of Ailes' path to becoming one of the most influential behind-the-scenes men in American politics are compelling enough to let us momentarily ignore how awkwardly they're presented.

The movie begins to find its feet in its second half, devoting the majority of screen time to the testimony of women whose lives were derailed by Ailes—ex. a woman recalls Ailes telling her, "If you want to play with the big boys, you've got to lay with the big boys," before he sabotaged her career for declining the offer. Their stories mingle with examples—Fox News broadcasts, more talking heads and stock footage—of Ailes' intentional manipulation of the American public ("We called it 'stirring up the crazies,'" says one former Fox employee). And then the credits roll.

The abrupt ending leaves us clutching at two aspects of Ailes: on the one hand, the hyper-paranoid true believer in "family values" and war between good and evil; on the other, the vengeful misogynist who spent his working life depriving women of their rights and careers. If and how those aspects are connected seems like the question the film should be trying to answer. Instead it settles for the image of Ailes as another fallen heavyweight from the white collar cesspool of American TV-politics. (Jon Auman)

A FAITHFUL MAN

Dir. Louis Garrel. 75 min.

U.S. Premiere.

Garrel's latest trifle is harmless enough, a near-sexless story of desire set in Paris that serves well as cautionary tale on idealizing crushes. Live-in boyfriend Abel (Garrel himself) is hit with a double-shock in the film's first minutes; girlfriend Marianne (a cool, earthy Laetitia Casta) is pregnant… with his best friend's child. Taking the news with nonchalance, Abel bows out and focuses on his career. Years later the friend suddenly dies, and at his funeral, at the graveside, Abel realizes he's still obsessed with Marianne. He finagles his way back into her life, once again becoming her live-in pet, but this time contends with her creepy, cop-friendly son who thinks nothing of recording his mother's sex life (we're supposed to find this cute). None of this sits well with now not-so-little sister Eva (Lily-Rose Depp), who also spent her brother's funeral musing on her crush Abel. She declares her intentions and Marianne decides if you love something, set it free. Abel manages to complicate what should be the world's simplest hookup, and the movie's remainder is everyone realizing what they actually want but being too passive to get it. The film is bizarrely edited, with unnecessary zooms interrupted as often as music cues suddenly cut out. From Why Not Productions, A Faithful Man begs the question, why care about characters so absorbed in their own immediate desires? (Danielle Burgos at TIFF)

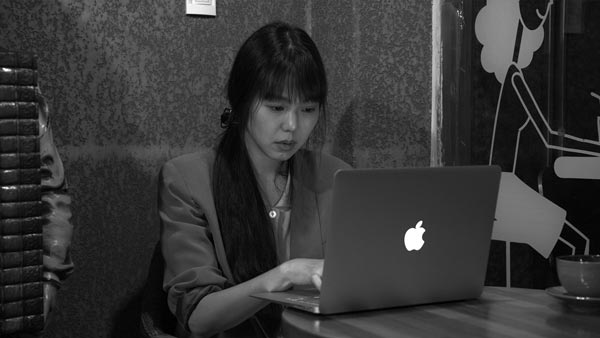

GRASS

Dir. Hong Sangoo. 66 min.

U.S. Premiere. A Cinema Guild release.

It turns out, Hong Sangsoo needs dramatic convention, or at least a little. Grass, his new barely-feature-length film, one of two in the Main Slate of this year's New York Film Festival, is an interesting enough workout of ideas but ultimately it's overcome by a weird emotional inertia. The "characters," as they are, can't quite figure out how to communicate with one another, and Hong can't quite figure out how to communicate with us. His most ardent fans, and there are many—his marital scandals are mulled over by some festival dorks with Tiger Beat fervor—will enjoy this as a kind of b-side curtain-reveal of a writer's process, but it's hard to get past the thinness. That this is the second year in a row the New York Film Festival has programmed two Hongs in the Main Slate says more about the festival's narrow if touching loyalty than it does about the quality of the work in particular.

Not to grouse too much. The foundation of Grass is what Hong does best—context-neutral conversations, falling somewhere between evasive and fraught, spiked with curious outbursts—so the film isn't totally unappealing. The hook here, if one can call it that, is that the coffee shop conversations are being eavesdropped on by a writer, played by Hong's muse, Kim Min-hee, with her trademark half-underwater delivery. Another filmmaker might exploit the private-public friction of this scenario—the eavesdropper set-up calls to mind a plot thread from '90s Woody Allen—but Hong more or less runs away from any hint of emotional/narrative/dramatic development. The conversations—touching on suicide, blame, romantic risk—intertwine and then evaporate. Incomplete narratives can sometimes carry a thrill for the audience, but Grass feels more like witnessing an already faint, colorless memory. If that sounds like your cup of tea, then let's be real, you're probably already a Hong-head. So enjoy it. (John Magary)

HAPPY AS LAZZARO

Dir. Alice Rohrwacher. 128 min.

North American premiere. A Netflix release.

Italian director Alice Rohrwacher's Happy as Lazzaro, shot in Super 16mm, is a magical-realist fable about the cloistered village of Inviolata, where the outlandish Marchesa Alfonsina de Luna (Nicoletta Braschi) presides over sharecroppers working her tobacco farm. Adriano Tardiolo, as the teenage Lazzaro, gives the finest film debut in recent memory. Stripped of guile, he beams with the same divine vacancy that suffuses the hypnotic performances of Pasolini and Bresson's nonprofessionals. Stiff-legged, clothed in a threadbare shirt and billowing pants, he takes up the tasks others find too demeaning or disagreeable with a holy acceptance: bearing "grandma" up and down the hill, passing the night in a stone-walled cage to watch for wolves, lugging the lion's share of tobacco leaves. His fellow peasants call his name in a ceaseless refrain, sometimes naggingly, but often with an eerie, omnipresent whisper. They tease him, too, with laughing affection. While the Marchesa exploits all of Inviolata's workers, Lazzaro is the laborer's laborer, tireless and obedient. Or is he? The late filmmaker Juraj Herz once cited the Czech quality of Švejkování : "subversion by being overly compliant." When Lazzaro's boss blusters that he should be in the field, the peasant remarks, with ingenuous calm, that he was ordered otherwise.

Inviolata's equilibrium slips with the arrival of Tancredi (Luca Chikovani), the Marchesa's petulant son, whose shock of bleach-blond hair, flip phone, miniature dog, and Walkman gesture to a world outside. He resents rural life, and the peasants spurn his authority with pointed insouciance. But Tancredi is charmed by Lazzaro's goodness ("Maybe he doesn't take advantage of anyone") and recruits him as a co-conspirator in his self-kidnapping, a paper-thin plot to swindle mama Marchesa out of a million-lire ransom. For a time, the odd couple dawdles in Lazzaro's hillside retreat, but when Lazzaro suffers from a saintlike fever, Tancredi's scheme, and all of Inviolata, unspools. Cosmetic changes, a leap in space and time reveals, have done little to reshape oppression. Our Lazarus regenerates; he is free—but is he happy? (Courtney Duckworth)

IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK

Dir. Barry Jenkins. 117 min.

U.S. Premiere. An Annapurna Pictures release.

With his third feature Jenkins creates the best and warmest of all possible nests for the two young lovers at the heart of the story. 19-year old Tish realizes she's in love with childhood friend Fonny; Fonny's always known he loved Tish and discovers a clarity and joy in sculpture. They've both managed to avoid the disease plaguing their generation, a feeling of worthlessness reinforced by looking around at the world. Tish becomes pregnant, and just as they begin to secure their life together, Fonny is arrested for a rape he didn't commit. Determined to have him released before their baby is born, Tish and her family push against infuriating odds as Fonny struggles with the unfairness of his situation.

Tish and Fonny have (mostly) understanding and supportive family, neighbors willing to step up to injustice, and friends able and willing to be emotionally open and honest. Exhausting struggle just to exist is the norm – finally securing a loft apartment after weeks of blatant racism and disappointment, Fonny has to ask the young landlord – why? He bashfully says he must be his mother's son; he's a sucker for romance. Yet gestures of kindness are fragile protection in a brutally antagonistic world; we spend the entire film terrified for them, the stakes all the higher because the love present is so strong. Jenkins performs a miracle avoiding bathos while baring raw emotion, presenting the cruelty of the world and its bitter fruit without dulling the love that makes living worthwhile. And all the while giving each character genuine depth, refusing to flatten even Fonny's holy-roller mother into caricature. To call it a romance would do disservice to the honesty Jenkins brings to bear on all their lives. (Danielle Burgos at TIFF)

THE IMAGE BOOK

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard. 90 min.

U.S. Premiere. A Kino Lorber release.

Jean-Luc Godard is 87 years old, and he's still working it out. He's bothering. He's Pizarro, he's Cortés. He bushwhacks with his eyes down. He doesn't care who follows his lead, and he's well past relying on the reality of an El Dorado. It's the ever changing ground beneath that mesmerizes him. He moves forward, because if he didn't, nothing would change.

Godard remains the most innovative film editor on the planet. If his "influence" as an editor remains narrow, it's because being influenced by Godard is to affirm the very premise of the Godard Editing Experiment. The constant cuts to black, the hard audio outs instead of fades, the Brechtian flouting of continuity. Editing is how cinema lies, always has been, but, as Godard proves again and again, the cuts need not hide away to retain their power.

His new film, The Image Book, whichcontains little in the way of new footage, isn't directed, exactly. It's pure montage, a wholesale recontextualization of scraps—from old movies, from Godard's movies, from symphonies, from the news, from reels to reels. The images, often tweaked—the resolution's crunched, or the color saturation's been turned up—come between pieces of text—presented, as always, in plain white, no serif—and stretches of black. Sentences are rarely completed. Occasionally, Godard himself narrates. His voice, at this point, is a tremendous croak. We're being talked to not so much from beyond a grave as from inside one.

"War is a condition of life," the film seems to say, yet at times this feels like Godard's warmest film in years. An orchestral motif calls to mind Georges Delerue's harrowingly gorgeous theme from Contempt. The soundscape is spacious—mixed in surround—and can only be fully appreciated in a good movie theater. Like the best Godard, The Image Book is shockingly new and heartbreakingly old-fashioned all at once. (John Magary)

IN MY ROOM

Dir. Ulrich Köhler. 119 min.

U.S. Premiere. A Grasshopper Film release.

For 2018's news-averse, Armin (Hans Löw) is the ideal TV cameraman. In My Room opens with his shaky handheld footage, craning to capture politicians' speeches about a German election. An inadvertent blessing: Armin turns the camera off when he intends to switch it on and, as a result, all the viewer glimpses is a frantic fumbling that excises the "important action." Director Ulrich Kohler, with this brief sequence, explains his film's remaining structure. In My Room is interested in elision, in the careful extraction of plot to make room for his fractured characters drifting through the uncanny landscape.

Kohler's camera, contrary to the opening shots, is calm and impassive, with a flat brightness. Armin's bosses scold him, of course, and the film tracks him as he bobs between failures—money troubles, aborted hookups, familial tension—like a neutered castoff from a slacker comedy. Still dutiful, he returns to his suburban home to sit vigil at his ailing grandmother's (Ruth Bickelhaupt) bedside. When she passes, the world ends. Or rather: Armin searches for his divorced mother and, seeing her busy with the similarly supernal matter of choir practice, swills beers under an overpass. Upon waking he can find no other humans on earth but himself.

Kohler skirts the expected explanations. (I overheard countless press members complain that no character ever asks, "What happened?") At first, the world is Armin's video game. He torches his family home and zips around in a police car. But in a moment of sudden grace, he cruises into a blackened tunnel and, hearing whinnies, releases trapped horses from a mangled transport truck; the echo of hooves in the dark conjures a moment of transcendence in the scoreless soundscape. Then Kohler cuts, and Armin is transformed, thriving in a light-filled house among livestock and rows of tended vegetables. These surprising images, as if a Kinfolk spread, feel too idyllic, almost aspirational. But as a new presence disrupts Armin's calm, Kohler again shifts his attention to more vital questions: What happens when humanity ends after capitalism? Who is Armin when his surrounding culture vanishes? Who is anyone? In My Room's best scenes are those in which our world is made eerily, terribly present. (Courtney Duckworth)

LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT

Dir. Bi Gan. 140 min.

U.S. Premiere. A Kino Lorber release.

Long Day's Journey Into Night has been declared a masterpiece before most audiences have had a chance to see it, but that does disservice to Bi Gan's risk-taking in what's only his second feature, where oblique dialogue is secondary to slowly unfolding set pieces reverberating and overlapping time and desire. Not all of his choices work, and at heart it's a mildly mawkish love story, but his boldness in telling is fascinating. The "masterpiece" label should be saved for whichever future work tempers tweeness and retains the audacity.

Returning to Kaili after 12 years for his father's funeral kicks off Luo Hongwu's Proustian, bisected tale of regret and longing as he searches for Wan Qiwen, the woman he's been unable to forget. The first half is ellipsed noir staged in supersaturated greens and reds. Relationships are stated but unclear. Is this their younger selves? A mother and son? Sprawling parallel possibilities? Longing is palpable but characters remain distant – in just one dense shot a snake strikes repeatedly at its glass cage as Luo stands near a window, a reflection reflected in a reflection of a train in the background that may not even be there.

Elegant silhouetted compositions give way to a single hour-long 3D shot; not gimmickry but a way to simultaneously put viewers in the film within the film while forcing an awareness that they're still watching one. Time stretches as characters move towards their desires, with several obvious plants – including spinning rooms and apples eaten whole – coming to bear, but ultimately, a moment of bliss holds its own brief eternity. (Danielle Burgos at TIFF)

MONROVIA, INDIANA

Dir. Frederick Wiseman. 143 min.

U.S. Premiere. A Zipporah Films release.

Frederick Wiseman's overlong survey of small-town Midwestern life opens with a montage of static views – fields, roads, houses, shops – as if flipping through a god-view cable package devoted solely to the title town. There's an intense sense of community, from a packed gymnasium of parents listening to an off-rhythm version of The Simpsons theme to a multigenerational montage of men getting (far too) high-and-tights at the barber shop. Throughout his career, Wiseman's genius has been presenting viewers with enough footage to draw their own conclusions, and giving subjects space enough to hang or reveal themselves. Here he's a little too generous, lingering on rituals and infrastructure that define lives without digging into any underlying beliefs. The first dip into the day-to-day, a high school history class where unmoved students hear a hagiography on the town's place of pride in basketball lore, suggests strong priorities that might not align with viewers'.

But in his attempt to neutrally present the dominating institutions of church, school, social clubs and sports, Wiseman overcompensates, only hinting at existing negatives. "Anti-PC" culture gets a brief sticker montage near the end, and racial relations are only inferrable by the few faces of color in the two-hour runtime. A tail-docking surgery at a veterinary office might be placeholder for casual slaughterhouse mutilation, scarcely suggested from the few herded cows and pigs shown. The finest moments are hearing actual opinions at a heated planning committee meeting. Still, anyone watching will feel like they've been to Monrovia, the best compliment for a documentary dodging judgements. (Danielle Burgos at TIFF)

PRIVATE LIFE

Dir. Tamara Jenkins. 123 min.

A Netflix release.

The exhaustions and degradations that come with making a baby in your poor forties is the subject of Private Life, Tamara Jenkins's third feature film in twenty years. (Her last, 2007's The Savages, was nominated for a couple Oscars.) At this rate, Jenkins is making one finely observed feature about every ten years, and the weariness in this one is as sharp as a hypodermic in the stomach.

Kathryn Hahn and Paul Giamatti play Rachel and Richard, East Village lifers many years into a loving-if-prickly marriage. They're smart company, funny, neurotic, age-aware, age-appropriate. They get on each other's nerves, get past it, then get on each other's nerves again. They share continental breakfasts in the nook of their airy two-bedroom apartment, a carefully painted, copiously bookshelved space that once, in a faraway time, was affordable to artists, which Rachel and Richard were. Rachel still writes fiction, but her career in the film is portrayed as marginal, almost painfully beside the point—the Yaddo artist colony is referenced multiple times, with deep, bittersweet nostalgia. Richard once thrived in the grant-fed experimental theater scene. Now he sells pickles. They live in that in-between and rarified realm of rent-controlled lower Manhattan, where money is scarce but dinner out is routine.

Rachel and Richard want a baby, but she's north of forty and he's shooting blanks. Time and again, they're assured that what they want, while complicated and draining and horrendously expensive, is not impossible. The film beautifully layers in one attempt after another to get a child: fertility treatments of every flavor, anguished discussions of adoption, surrogacy. "This is kind of kinky," Richard says, as he and Rachel, lying in bed, hunt through a database of attractive, young egg donors. Ultimately, the donor they agree on is Richard's brother's 25-year-old step-daughter, Sadie, a Bard dropout played by Kayli Carter with just the right amount of overbearing, appealing self-confidence. This shabby triangle forges ahead and—well, things don't get much easier.

Whether a movie like Private Life is successful or not for the viewer depends on the reach of its observations—the ins and outs of processes, cultural references, behaviors, authenticities. Rachel and Richard's expensive middle-aged struggle is by necessity specific and narrow, and so is this world. The shouted out include Karl Ove Knausgaard, Eileen Fisher, Wendy Wasserstein, and—perhaps most gratifying to Screen Slate readers—Anthology Film Archives. The fertility doctor likes prog rock. Familiarity with the world aids the pleasure.

If, in the end, the movie feels a little suffocating and overlong, it's partly by design. Jenkins's point is clear: the struggle to conceive is embarrassing, deflating, harrowing, and in the end, maybe—maybe—joyful. At the very least, Jenkins argues, having a child is clarifying. (John Magary)

RAY & LIZ

Dir. Richard Billingham. 107 min.

U.S. Premiere.

Misguided in a way that only artist-made features can be, Richard Billingham's Ray & Liz is a bland, joyless, poorly conceived, and haphazard dirge. The premise is thorny but fascinating: a narrative film linked to a long-running autobiographical portrait project by the Turner Prize-nominated photographer. To unpack that: in the 1990s, Billingham took a series of seemingly off-the-cuff pictures of his immediate family, including his parents Raymond and Elisabeth, a pair of chain-smoking alcoholics living in working-class squalor in a messy Stourbridge council flat. The provocative series, which has garnered comparison to Nan Goldin and Larry Clark, is willfully knotty and problematic; it's also heartfelt, funny, and shocking.

Twenty years on, it's unclear why Billingham has decided to create a narrative feature version of this project with (reen)actors. The artist himself said, "by sticking true to real life, lived experience and observation I want to recreate a world that can only have come about from my being a witness to it." Although lived experience and personal observation is surely a valid asset to a filmmaker, it alone isn't enough to make a fully realized film – there isn't much in the way of narrative construction, dramatic finesse, or cinematic craft here. Instead, we witness what strikes me as an underdeveloped conceptual exercise to restage documentary photographs, which results in a frankly banal cycle of provocative moments including excessive drinking, vomiting, and violence, without perspective or purpose. When it comes to still frames versus twenty-four-per-second, quantity doesn't necessarily mean quality. (Jon Dieringer)

ROMA

Dir. Alfonso Cuarón. 135 min.

Centerpiece selection. A Netflix release.

Shot in black and white and deeply autobiographical, Cuarón's latest could lazily be compared to Fellini's8 1/2. But instead of navel-gazing, Cuarón mines his memories to tell the story of two women of different means coping with abandonment under the same roof, while 1970 Mexico changes rapidly around them. At a TIFF Q&A, Cuarón explained all decisions, including working as his own cinematographer and shooting on 65mm, were made to convey childhood memories as if he were a ghost revisiting his own past at a distance. He often hovers just behind Cleo, live-in housekeeper and nanny of an upper-middle-class family. Stories like hers are often erased from history, and it is a painful joy to see them told with dignity and loving detail, capturing the difficult dynamics of straddling bifurcated roles of hired help and beloved family member. Sibling fights, hurled insults, earthquakes, riots: Cleo bears them with quiet fortitude, her control so great she alone is able to hold the miracle stance a hundred government-backed Halcones stumble trying in training. Playing Cleo is Yalitza Aparicio, a preschool teacher in Oaxaca with no previous acting experience who lets emotion break through Cleo's placidity like sun through clouds. She balances Sophie, woman of the house, whose raw nerves over her husband's jilting Cleo sees but can't break social boundaries to comfort. Herself pregnant and abandoned by her arrogant boyfriend, Cleo's stomach swells alongside the unrest sweeping through Mexico, as the two women face uncertain futures. (Danielle Burgos at TIFF)

TOO LATE TO DIE YOUNG

Dir. Dominga Sotomayor. 100 min.

U.S. Premiere. A KimStim Release.

Dominga Sotomayor's third full-length film, Too Late to Die Young, for which she won Best Director at this year's Locarno Festival, features two recordings—one English, one Spanish—of Mazzy Star's velvet-voiced ballad "Fade into You." It is the post-Pinochet Chile of the 1990s, and the teenage Sofía (Demian Hernández) is apt to brood. Her large eyes, planar cheekbones, and shorn brown hair lend her a gawky grace, fit for wandering her forest home in an oneiric malaise. Surrounding Sofía is a ragtag crew of bohemian families—painters and actors, musicians and craftspeople—who have made these rolling hills an insulated paradise that, at first, seems to dwell apart from outside concerns. Children traipse half-clothed through craggy streams; couples sleep with trusting supinity in open-plan houses, through whose wooden beams golden light filters hazily, thanks to Inti Briones's deft cinematography. As in the films of Lucrecia Martel, it is hard to pin down who belongs to who, but the muddled relationships only heighten the sense of a sprawling utopia.

Edens are often erected to be razed. Unexplained crimes—break-ins, redirected water pipes, wildfires with no set cause—disturb the saccharine surface. Debates rage over introducing electricity into their frangible world. A beloved dog goes missing and, when it resurfaces, seems a changeling. Crises are always, first with confidence and then with wavering, uncertain voices, attributed to "outsiders." Sofía, meanwhile, yearns to leave the rural landscape of her laconic father for her divorcée mother, a famous singer in the city; and she circles a crush on an older, feckless man as if unable or unwilling to escape his orbit. All these frayed strands find their endpoint in a dead-of-night New Year's fête: an occasion with enough flint to start the emotional and actual conflagrations that could, perhaps, inspire new growth. (Courtney Duckworth)