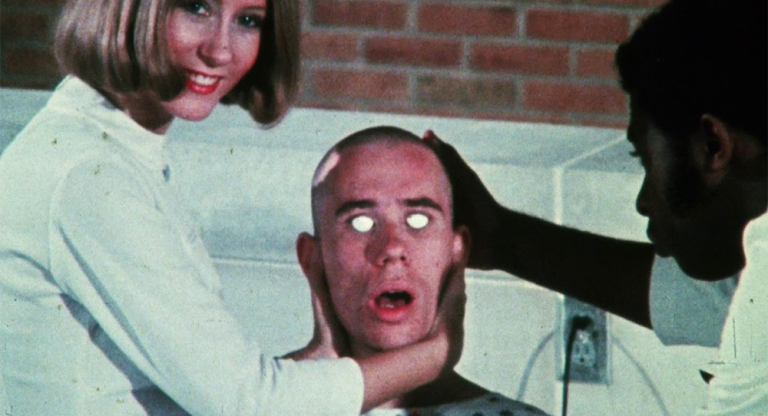

The Wrong Man (1956) is a strange outlier from the most celebrated period of one of the most celebrated filmographies of all time, sandwiched between The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) and Vertigo (1958) within Alfred Hitchcock's body of work. It’s also his sole collaboration with Henry Fonda, here playing Manny Balestrero, a real-life Stork Club musician who was erroneously identified as the culprit in a series of insurance-company robberies in New York in 1953 before the actual perpetrator was found. Much has been made of Hitchcock’s fidelity to the record, involving NYPD detectives as technical advisors and shooting as many scenes as possible in real-life locations around the city, including Balestrero’s home turf of Jackson Heights (and an elaborate courtroom coda shot in Ridgewood.) The film’s publicity campaign stressed its ripped-from-the-headlines urgency and Hitchcock does the same thing in its opening moments, substituting his usual embedded cameo for an anterior declaration of intent that anticipates his droll approach to introducing broadcast episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

All this historical context makes it difficult to enter The Wrong Man without a certain amount of awareness. Manny’s exoneration is a foregone conclusion borne out by the movie’s existence, so I found myself asking… What’s in it for the Master of Suspense? When Manny enters the company office in pursuit of a loan to pay for his wife’s dental work, Hitchcock clocks the apprehensive looks of the women working at the cash register, especially when Manny reaches into his pocket to produce documentation of his insurance policy. His innocence has been established up front, so what really seems to interest the filmmaker is the way detectives accumulate evidence that corroborates their suspicions, spurred on by testimony from witnesses (namely the aforementioned women, still traumatized from being robbed at gunpoint) who bring their own baggage to the process. The lack of plot twists is the plot twist. What follows is a linear procedural depiction of the system grinding Manny to a fine dust as he seeks to prove his innocence, and a rare detour for Hitchcock into the realm of Dostoevsky, Kafka or Sartre.

Fonda, the eternal do-gooder, is not exactly cast against type as a clear-eyed victim of an unfair system, but suspense grows as he protests what’s happening to him with growing desperation. The straightforwardness of Hitchcock’s approach means there’s a lot of time spent waiting for the other shoe to drop: What if Manny lied to his wife and kids about his whereabouts? What if Hitchcock hasn’t shown us everything? As a meditation on the human biases that prevent the United States’ vaunted justice system from doing its job, The Wrong Man complements 12 Angry Men but avoids Fonda’s liberal speechifying—to say nothing of Sidney Lumet’s tendentious close-up of the doe-eyed, wrongfully accused teenage John Savoca, which offsets the deliberations that follow. In conversation with The New Yorker’s Lillian Ross, François Truffaut eagerly aligned The Wrong Man with Robert Bresson’s contemporaneous A Man Escapes (1956), and logistical concerns become existential through the Catholic lens shared by Hitchcock and Bresson. Even if your papers are in order and your record clean, it’s impossible to be totally sure you’ve built a secure life for yourself and your family. Or, per the film’s nervewracking tagline: “An Innocent Man Has Nothing to Fear!”

The Wrong Man screens tonight, December 16, and tomorrow, December 17, at Film Forum on 35mm as part of the series “Hitchcock and Herrmann.”