When director Abel Gance decided to bring the story of Napoleon to the screen, he planned to tell it in a series of six films. He only got through the first before running out of money. But he still managed to edit together over nine hours of footage, which follow the titular character from his childhood in Brienne-le-Château through the French Revolution to his marriage to Joséphine de Beauharnais and his subsequent invasion of Italy.

The first shot of the 1927 masterpiece is of Napoleon’s iconic bicorne, bobbing up and down behind a wall of snow. It could be a scene from his icy and ill-fated invasion of Russia, until we see the hat is being pelleted by snowballs and boy Napoleon at last fills the frame. Gance often collapses time, playing with his audience’s familiarity with the historical person. Some scenes later, during a lesson about islands, the teacher lectures about the boy’s birthplace, Corsica, and what would be his place of exile, Sainte Héléne.

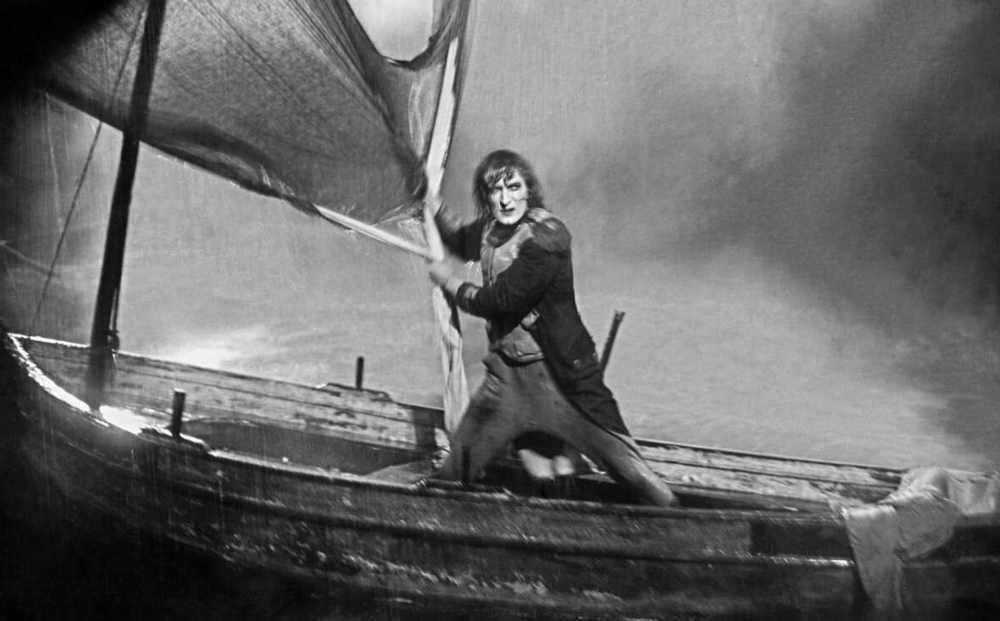

At times, a mythological Napoleon seems to overwhelm the film, as Gance sometimes equates his character with the French nation. For example, a heavy-handed scene has Napoleon, on a boat whose sail is the tricolor, pulled by wind and waves while spliced with scenes of Robespierre and company conspiring against him. Still more, in a scene where Napoleon is called to defend Paris from a Royalist rebellion, he takes command, announcing himself the embodiment of the Revolution, while his shadow darkens a copy of “The Declaration of the Rights of Men.” Here Gance betrays his challenge to depict Napoleon’s cultural paradoxes. And yet, he stills crafts a human portrait of Napoleon by also attending to his character’s psyche—shooting incisive close-ups of his lead, Jean Dieudonné, that prefigure Dreyer’s Joan of Arc; super-imposing images to evoke Napoleon’s state of mind, as in the case of Josephine Bonaparte over an active battlefield. A romantic with a near-obsession for D.W. Griffith, Gance held equal reverence for both his subject and his medium. His film, as a result, was both way ahead of its time and yet politically messy, regressive, and even fascistic in its marriage of individual and nation.

A screening of Napoleon is a momentous occasion. The obsession cinephiles have for it is not unlike Gance’s of its subject. Screenings are infrequent—the last one in New York City took place at Radio City Music Hall in 1981—and most have used truncated cuts and remixed collages of the original, both because of bad distribution deals and Gance’s obsessive post-release tinkering. Kevin Brownlow, who first discovered the film in 1954 and has since been collecting and restoring as many old reels as he can find, has recomposed what is now a five-and-a-half-hour approximation of its first unadulterated screenings. A film preservationist of the first order, Brownlow, like Gance, has had a lifelong commitment to Napoleon and is largely responsible for the film’s contemporary reevaluation. While a seven-hour version recently screened in Paris, Brownlow’s project of realizing his Napoleon may be just as ill-fated as Gance’s before him, notwithstanding their significant contributions to their fields.

Napoleon screens this afternoon, November 2, at Film Forum as part of the series “Kevin Brownlow.”