Part of our cultural revolution must be to protect the reality of Malcolm's life, because that is the only way we will protect the reality of our own, and the actual historical gravity and meaning of our struggle. This is the reason we ourselves must take our struggle into the schools, into the movie studios, the theaters, the concert halls and nightclubs. It is why we must build cultural and educational and arts institutions to provide an alternative to the poisonous fruits of the American superstructure, even though we must not abandon our struggle for influence and control over those sectors of the superstructure where such relationship is possible.

This is why we are in contention about Malcolm's life and image

and history. This is why imperialism and white supremacy and their little running dogs are too.

—Amiri Baraka

In his 1972 essay “Take Me to the Water,” James Baldwin described how a frustrated effort to stage a theatrical adaption of The Autobiography of Malcolm X turned out to be the prelude to his half-hearted agreement to try again with a cinematic translation for Columbia Pictures in 1968. He was caught between the conviction that Hollywood “doing a truthful job on Malcolm could not but seem preposterous” and a sense of obligation given that Malcolm X “had trusted me in life and I believed he trusted me in death.” Ultimately, Baldwin explains that he did not follow through on the project out of a refusal “to be a party to a second assassination.”

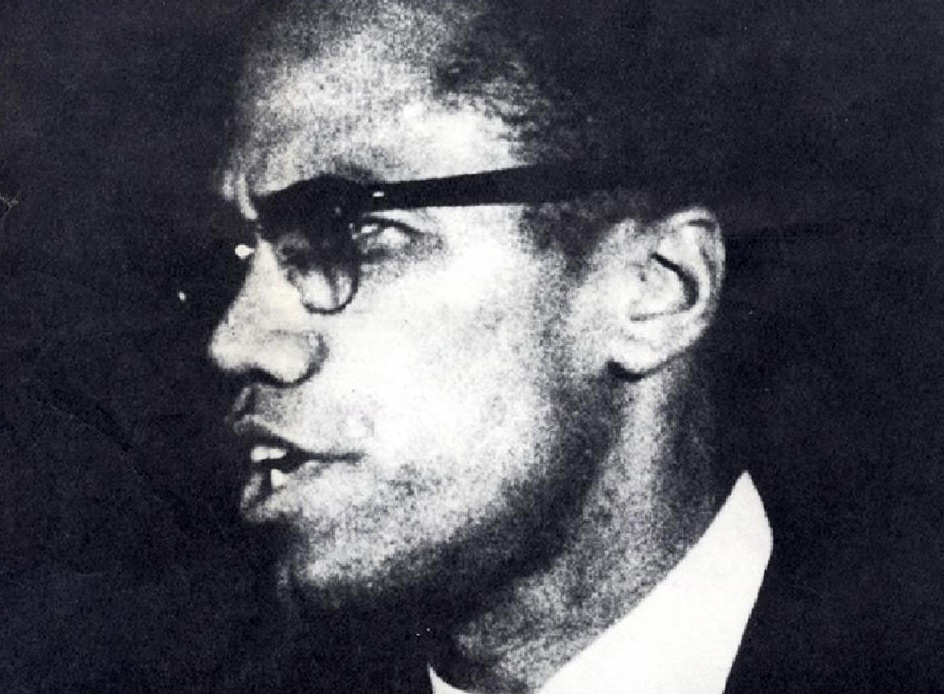

When the martyr of Black Liberation was shot on February 21, 1965, he had been known as Malcolm Little, Malcolm X and el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz. Endlessly photographed, filmed, written about and spoken of in life, his visibility only rose in death. As the subject of books and manifestos, paintings and murals, poems and lyrics, he has been continually studied and fictionalized, replicated over and over as a material and virtual palimpsest of representations.

In 1959, the television-watching American public first met Malcolm X as part of The Nation of Islam in The Hate that Hate Produced. The documentary skirted anything like a good faith critical chronicle in favor of leveraging the perverse fabrication of “Black racism” to serve a delegitimizing caricature of Black Nationalism writ large. Baldwin may well have had exactly such chicanery in mind in declining to participate in what he prophesied as a reputational assassination, on similar politically and culturally consequential terms. Regrettably, the collusions of capital and white supremacy channeled through Hollywood, dominant media, and conventional education have since made countless attempts to nail down a manipulated and distorted memory of Malcolm X.

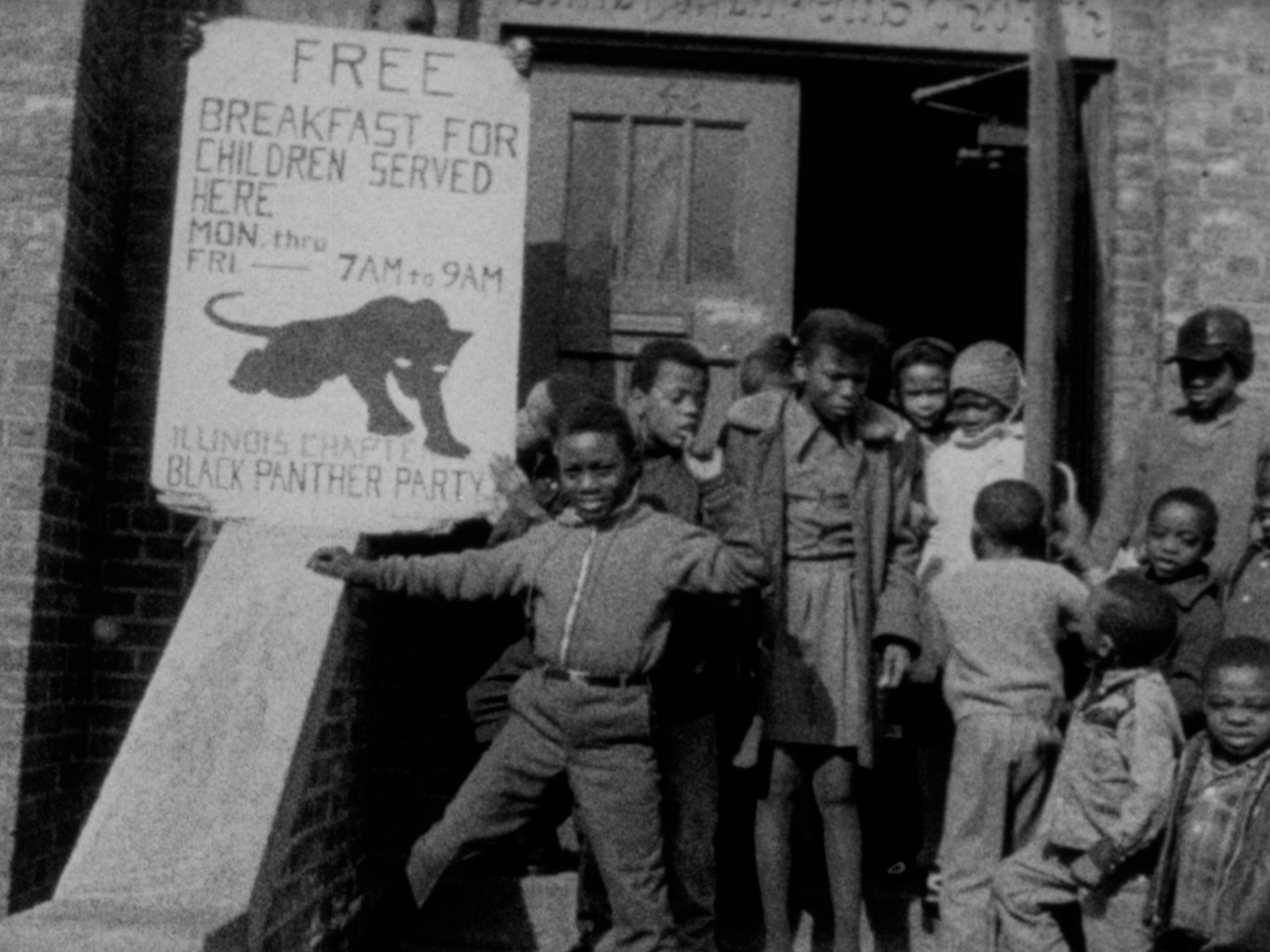

Yet even as he was taken down by bullets, Malcolm X has continued to be a fugitive target. Neither diluted nor demonized portrayals have ever stuck enough to impede the transformative force of his legacy. In every way a moving image, his representational mobility traverses mediums and forms in the same way he was always on the move, not only traveling widely but shifting and expanding his ideas throughout his life. Malcolm X keenly understood how the game of popular perception was rigged and evolved to be a media maestro, carefully choreographing his public performance toward the political ends of global liberation. He had a formative influence on the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, whose sartorial signature was one of many ways they too strategically wielded their image and media as revolutionary tools. Malcolm X has not only shapeshifted across a transnational visual vernacular, he has contributed to a critical understanding of its function. Always a dedicated teacher and student, tracing the cultural narrative of his remembrance is itself pedagogy in practice.

As much as anything, his passage through a genealogy of audiovisual memory resists any singularity. As Baldwin wrote, there is “a Malcolm, virtually, for every persuasion.” Even the autobiography, which has been the central text of adaptations of all kinds, broke with the foundational convention of the genre. A haunted text, it was posthumously co-authored with the journalist Alex Haley, making it a mirror and a mask, a first-person narrative written by a second person—arguably all the more malleable to cinematic translation. The cultural critic and musician Greg Tate declared “the brother had style, […] never took a bad photograph in his life” and also “had a multiple-identity crisis going on.” Malcolm X was a self-authored and externally written myth who is only recognizable as many-sided. Tate is amongst the many Black writers, artists, critics, scholars, and cultural workers who have participated in the collective work of memorializing him while simultaneously dissecting and interpreting the terms of that process. Preeminent amongst them, the author of Malcolm X: The Great Photographs (1993) and librettist for the opera “X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X” (1985), Thulani Davis cautions against mistaking surface and icon for substance and ideas, describing how “X, the ultimate reduction of all Malcolm’s words and ideas, has become a symbol, a badge of belonging and a sign of cash sales.”

The symbolic currency of Malcolm X has indeed made him a profitable object of commodification, the political and spiritual breadth of his legacy narrowed into a defanging machinery of consumption. Filmmakers and video artists have taken these mercenary procedures to task. In the slyly titled Perfect Film (1984), Ken Jacobs unmasks the norms of TV media and use of visual evidence via what he calls the “the out-takes of history.” Two exemplary works emerged in the 1990s, No Sell Out… or i wnt 2 b th ultimate commodity/ machine (Malcolm X Pt. 2) (1995) and X – The Baby Cinema (1992), by the multiform quartet X-PRZ and skilled artisan of celluloid Robert Banks, respectively. While the first makes efficient use of desktop video technology, archival materials, musical samples and a stylistic pantomime of MTV to critique to the appropriation and misuse of Malcolm X’s image for profit-driven commercial culture, the latter is a 16mm analytical collage, toying with reappropriation to expose the mechanics of power at play in his visual memory.

Spike Lee’s 1992 biopic, which certainly had a significant hand in a resurged and augmented public awareness of Malcolm X, perfectly captures what Baldwin had turned away from. Hollywood fare through and through, the limiting U.S.-centric narrative leans on the salacious and the spectacular in a sweeping erasure of a life arc of profound intellectual, ideological, political, and spiritual depth. Many more Black filmmakers have been the source of image-making to the measure of remembering the fullness of Malcolm X, mobilizing the intertwinement of aesthetics and politics to re-author a common understanding of the collective liberatory history within which he was and continues to be embedded.

John Akomfrah’s quicksilver experimental film Seven Songs For Malcolm X (1993)—which features both Davis and Tate—models how such efforts have required breaking and remaking cinematic language. Made while he was member of the Black Audio Film Collective, it combines a jazz-informed sonic architecture with stylized tableaux and sculptural stillness to offer a supple and knotted study of memory-making. Never a singular image, the remembrance of Malcolm X also travels through a chorus, as the narration by Toni Cade Bambara threads a multi-voiced testimony. Betty Shabazz is a guiding presence in Seven Songs, as in many filmic tributes, in some cases onscreen and in others advising the production process. Her centrality points to the magnitude of women’s influences on Malcolm X, which included his sister, Ella Little Collins, Vicky Garvin, and Grace Lee Boggs. While generous with insights, Betty Shabazz also signals the necessity of camouflage around the Malcolm X that was only for his close kin to know, safeguarded from public consumption.

Within the current reigning order, a thickening miasma of worldwide fascisms and newly augmented Islamophobia, the Malcolm X called forth the most urgently is the one who became a crossroads for Black Liberation as part of an anti-colonial and anti-imperial Third Worldist struggle against global oppression and exploitation. He has a place next to Thomas Sankara, Patrice Lumumba, and Amílcar Cabral as much as Martin Luther King Jr.—who, despite the work to paint him and Malcolm X as two irreconcilable antipodes, was also assassinated when he had moved toward a similarly internationalist set of positions.

Malcolm X founded the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) in 1964, after his return from Mecca, calling for a political education and cultural revolution. He stood in solidarity with Palestinian Liberation, the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya, the Cuban Revolution, and the anti-colonial battles of the Vietnamese and Algerian peoples. The enduring importance of this lineage is evident in documentaries made soon after his assassination, as in the case of Malcolm X: Struggle For Freedom (1967) by Lebert “Sandy” Bethune—a Jamaican poet, educator, and documentary filmmaker who worked in an orbit of Black writers, artists, and thinkers linked to Négritude and revolutionary militancy—and Charles Hobson’s Malcolm X Speaks (1971), as well the more recent Malcolm X And The Sudanese (2020) by Sophie Schrago.

Another crucial node in the intertwinement of visual culture and the memory of Macolm X passes through the work of Black independent documentarians and television producers, perfectly encapsulated in the pioneering Madeline Anderson’s A Tribute To Malcolm X (1967). Her elegantly efficient and multifaceted portrait was made for Black Journal (1968-1977), the first nationally televised public affairs program to focus on Black people under the direction of Black media workers. As detailed by one of the original producers, the towering documentarian and organizer St. Clair Bourne, in his 1990 article “The African American Image In American Cinema,” Black Journal emerged in the wake of the insurgent unrest of the waning Civil Rights, as unchanging conditions of discrimination and dispossession met frustrations with the white mainstream media. A collaborative cohort under the leadership of William Greaves, Black Journal created an avenue to focus on Black communities that prioritized independence and self-determination, covering political, cultural, economic and social topics with international breadth. Inventing a television format that would later be copied by mainstream broadcast networks, it significantly influenced Black documentary practice. Black Planet Productions was a video collective founded in the 1990s by artists and filmmakers in New York working under the Gil Scott-Heron-inspired motto, “The Revolution, Televised.” Their experimental documentary X 1/2: The Legacy Of Malcolm X (1994) toggles between historical narrative and contemporary interviews to revisit a mercurial evolution of memory. Although working through a different structure of production, they might be seen as indirect inheritors to Black Journal in their cooperative approach to challenging moving image conventions to articulate a political and aesthetic vehicle for autonomous Black knowledge.

Numerous photographs show Malcolm X with a camera in hand. He was both an image and an image-maker, intervening directly in what could exist as a visual record. Throughout his travels, he collected records of the umma, as well as demonstrations and protests, that could offer a counter-archive to the violent documents of surveillance weaponized against him and many others. Mediatized and multidimensional, he too was a memory worker. Malcolm X is a media study, unfolding a narrative of cultural memory and the mechanisms of mythmaking encoded in the history of cinema and audiovisual media. He could never be contained in even the most rigorous documentary any more than he could be contained within the limits of his singular person, always a part of a still active internationalist commitment to recreating the terms of collective coexistence. There was never only one Malcolm X, he was for the many and he exists many times over.

Malcolm X: Multidimensional runs September 11-21 at Anthology Film Archives.