“A tidal wave is coming. Soon, I am sure, it will sweep us all away.” The destruction of Japan by the surging, scouring ocean: this is the unforgettable portent that opens Shinji Aoyama’s Eureka (2000). It is delivered by a young girl, Kozue (Aoi Miyazaki), one of three survivors of a bloody bus hijacking for which no motive is ever revealed. Her brother, Naoki (Masaru Miyazaki), and the bus driver, Makoto (Koji Yakusho), are the others.

Aoyama’s early films, including Eureka, take place across a backdrop of brutality because they are righteously angry at the world. Through his lens, Japan at the cusp of the new millennium was a land ruptured by stochastic violence, captured by cults, and damned by the delusions of the emperor system. Aoyama, also a brilliant film critic and theorist, believed that cinema could only avoid reproducing this dead-end present by rebuking the nation and its definitions of “politics” and “humanity.” This effacement of national pride and identity also meant rejecting the symbolic beauty of the landscape from which Japan derives its imperial authority. No cherry blossoms or serene temples in this film—much of its four-hour runtime takes place in an unglamorous town, by weed-choked rivers steaming with trash, barren fields, and hills scraped by excavator claws.

Aoyama owes these sensibilities to his foremost literary inspiration, the burakumin writer Kenji Nakagami. The burakumin are an ostracized underclass in Japan whose oppression stems from religious notions of uncleanliness associated with certain occupations and transmitted through bloodlines. Nakagami’s stories turned away from idealized landscapes to depict the cloistered buraku, or ghetto, and its residents’ attempts to escape family ties. The family unit is also fraying in Eureka. In the wake of the hijacking, Makoto, wracked with survivor’s guilt, leaves his wife to wander the earth for years. Kozue and Naoki’s mother vanishes, their father dies, and they stop speaking and attending school. Those abandoned by society or unable to conform to it—these are the people Aoyama thought cinema should put before us. As individuals who represent only themselves, they bring into existence a new way of living in their struggle against the world.

When Makoto suddenly returns to town, women are killed in a string of murders, and the police single him out as a suspect even though they have no evidence. Pressured out of town again, he lives on its outskirts with Kozue and Naoki in their lonely house. Stigmatized by rumours about what “really happened” to them on the bus, they have shut themselves in. The film is sparse on dialogue, manifesting a deep corruption of language in the face of loss and death. Language in Eureka is cast as what Paul Celan termed “murderous speech”—for Makoto and the siblings, to use language is to participate in judgemental discourses designed to segregate them and mark them as unfit for life. Instead, they perform nearly wordless acts of care for each other throughout the film, weighting minute gestures with tenderness amidst their bleak surroundings.

The children’s cousin, Akihiko (Yoichiro Saito), also arrives at the house, sent by relatives to check on the orphaned kids. He too bears a dark past that he is reluctant to reveal. Realizing that they must all move on from what they’ve gone through, Makoto brings them on an impromptu road trip, beginning from the site of the hijacking. Aoyama complicates this journey, often showing the characters moving in circles or ending where they started. Even the steering wheel and tires of the RV that Makoto buys for the trip, which return to the same orientation no matter how much they revolve, metaphorize this tug-of-war between repetition and change. In this way, Eureka is not just a story of “inner healing.” It aims outwards, implicating the vicious cycles of history and the complacency of everyday life: how can we possibly live in—and forgive—a society that allows people on its margins to suffer so terribly?

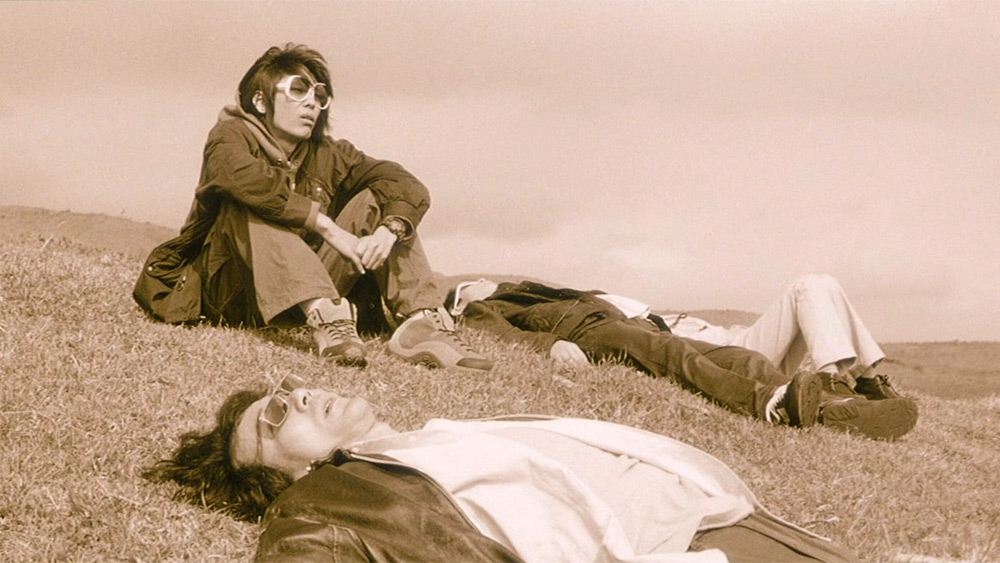

Eureka was shot on black-and-white film, but printed using experimental processing techniques as a color positive with an iconic sepia tint. Variations in darkroom conditions meant that no two prints struck of the film were alike. Even its cinematographer, Masaki Tamura, didn’t know what print should be considered the definitive one. This too was a reflection of Aoyama’s philosophy of film, a way of affirming the singularity of original lives in a medium ostensibly built upon reproduction. In a 1997 manifesto, Aoyama boldly claimed that “There was no Nouvelle Vague in Japan,” arguing that even films by the Japanese New Wave could not resist recuperation by the state as symbols of its power to re-present those it subordinated. A “liberated” cinema, on the other hand, had to occupy a space of political exception, pursuing dissensus and the opportunities created by chance, improvisation, and entropy. As Ryan Cook explains in NANG Magazine,

When Aoyama ventures a definition of politics, he cites [Nagisa] Oshima, the political filmmaker, but Oshima once quipped that politics is something one does ‘with other people’s money.’ Oshima’s politics was fundamentally social and pragmatic… Politics for Aoyama seems to mean something different in 1997, something more personal, related to self-realization and world-making… [it] is not as simple as convincing others to invest money in a cause; it is a more fundamental problem of the ability to understand and communicate with others.

Aoyama’s fans include directors as varied as Bong Joon-ho, Pedro Costa, Olivier Assayas, and Ryusuke Hamaguchi. Those who have seen Eureka (2000) often describe it as one of the greatest films ever made. That said, this praise and canonization is dangerous. Aoyama should not be placed on a pedestal. Not because he wasn’t great, but because his career was devoted to smashing such pedestals. In fact, the slowness and duration of Eureka makes it an outlier in his filmography, which consists largely of nimble, rascally genre experiments (which are truly radical in their own right, and unfairly overshadowed by Eureka’s stature). Eureka is not the summit, but the starting place. It is the work of a young filmmaker pushing every limit of his medium, and it shakes the foundations of cinema to arrive at an experience of profound ruination and revelation.

Eureka screens this evening, September 14, at Asia Society as part of the series “Dennis Lim Selects.”