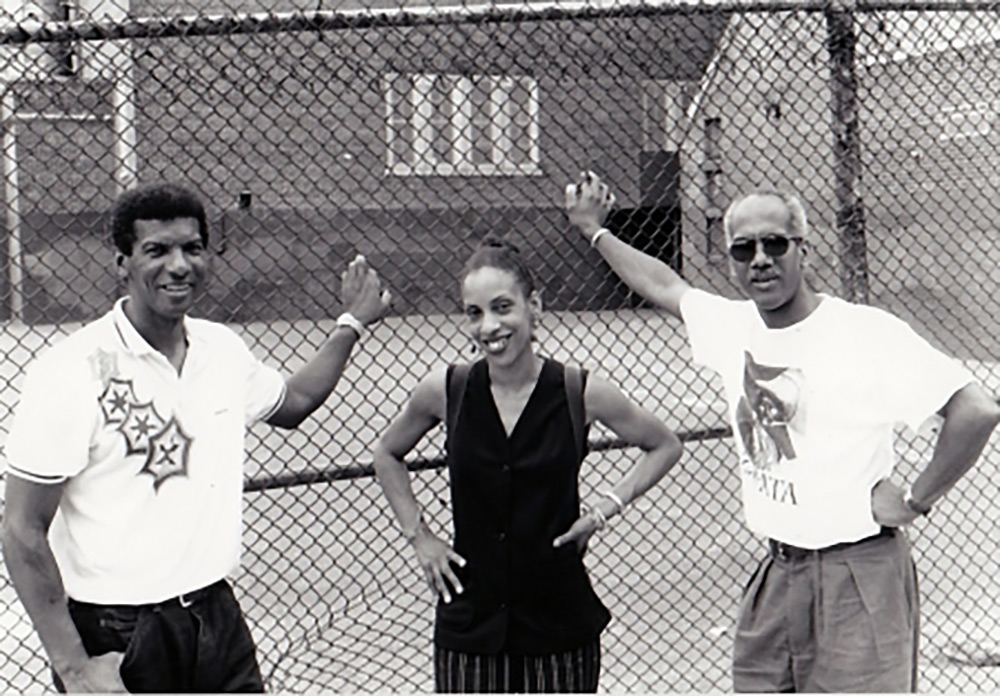

The lives and culture of Afro-Latinos, especially Black Cubans, are rarely depicted on film. It’s for this reason that Cuban Roots/Bronx Stories: An Afro-Cuban Coming of Age Story (2000) has remained an important gem in the Afro-Latino film canon for 25 years. The documentary chronicles the story of the Fosters, an Afro-Cuban family of Jamaican ancestry that immigrated to the South Bronx from Cuba in 1960. In 57 minutes, director Pam Sporn offers a detailed portrait of the Fosters’ rich family history told through the lens of three of the seven Foster siblings: Pablo (Pam’s husband), Diana-Elena, and Ruben.

It is not only the film’s representational politics that are unique, but its understanding of migration and its relationship to the Cuban Revolution, which contrasts greatly from the American status quo, cinematic or political. Very quickly in the film, audiences learn the Foster siblings were not escaping the Cuban Revolution, a common reason for Cuban migration to America, but were fearful about a potential U.S. invasion of their home island. After their neighborhood was bombed during the Bay of Pigs invasion, the Fosters’ mother thought it was best to leave the country, which ultimately brought them to the South Bronx. There, the family was subjected to a whole new political reality where they struggled to navigate their black and Cuban identity in a society that was incapable of accepting either.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Pam as Cuban Roots celebrates its 25th anniversary. In this conversation, she shares more details about the Fosters' vibrant family history and explores the production process of this documentary, which is a true feat of independent filmmaking.

Fabrice Nozier: You are, of course, intimately tied to this story, being that Pablo Foster is your husband. At what point did you realize that this story about Pablo and his family not only had to be told, but should be communicated on film?

Pam Sporn: I had always been interested in Cuba coming from a left-wing activist background. When Pablo and I got together, he would tell me stories about growing up in the Bronx in the ‘60s, and as I got to know his family more, I would hear all kinds of conversations about coming from Cuba. I told him that he should write a book about these experiences. That didn't happen. Back then, I was beginning to experiment with video documentaries and decided this would be something I could do.

I was also doing my masters in Spanish literature at City College, and I took this class called “Ethnolinguistic Bilingualism and Ethnolinguistics.” One of the class assignments was on code-switching, how people who speak two languages switch between those languages. We needed to conduct language samples from people. One of my interviewees was my sister-in-law, Geraldine [Cuty] Foster, who's not in the film, but I learned so much about her family and growing up on University Ave. in the Bronx. She came from Cuba when she was 16, and she’s Pablo’s oldest sibling. In this interview I did with her, I just started asking her about Cuba.

She told me about how she had participated in the literacy campaign, which was this massive effort by the Cuban government after the Revolution, in 1961, to alfabetizar, bring literacy to the whole Cuban population. She participated in the campaign as a teenager and she loved it. Her parents were afraid for her safety, and they didn't let her go up into the countryside. Instead, she participated in the campaign in Havana. After school, she would go and teach this older couple how to read and write. This was a story you hear about in history, and here she was telling me she had been a part of it and how important it was to her life. It was one of the reasons why she didn’t want to leave Cuba. My husband and his siblings were excited to leave because they were younger, but Pablo remembers her crying about the move. That story really stuck with me.

I was becoming part of this Cuban family that was not anti-Revolution. Pablo got involved in very left-wing politics as a high school student and continued on as he worked in Bellevue Hospital as a union organizer. The political stance of the family was so different from that of the stereotypical white upper-middle-class Cubans who, at the time, wanted to destroy the Cuban Revolution. This was such a unique position, and I felt it was important for this story to be told.

FN: You're really able to show a plural and more complex understanding of the Revolution, Cuba, and migration. In the film, the Fosters express how their mother wasn’t opposed to the Revolution, but was just worried about the family’s safety, which is why they left. Their neighborhood, as you show, was bombed in the early ‘60s by the U.S., and she was anxious about the prospect of a U.S. invasion, which was, of course, attempted during the Bay of Pigs.

PS: There were mixed opinions, as you see in the film. My father-in-law, Carlos Foster, was not pro-Revolution or pro-Castro.

The Fosters lived in Guamá, in the eastern province of Cuba, with their aunt during the period of the Revolution’s armed resistance. There were guerrillas in the nearby mountains, and Pablo remembers that one of his cousins by marriage, who was around 18 at the time, left in the night to join the Revolution. They hadn’t seen him until later, after the Revolution was won, and the family was all living in Havana. That moment remained in the fabric of the family history and formed that consciousness.

This question about why people leave their homelands still resonates so much. The film understands migration in a global way and how it’s connected, not just to individual choices, but why individual choices are related to the circumstances created by world powers and imperialism. This is how to understand the Fosters’ family movement and why the mother would want to leave Cuba with seven children. All of Veronica’s siblings actually left for New York, the Bronx, in the ‘50s, before the Revolution.

You can imagine here in New York, the attitude toward the Revolution by the mainstream was negative. There was a lot of pressure from her family in the Bronx, knowing that their sister was in Cuba. They wanted her to be safe. They’re the ones who actually facilitated the Fosters’ coming to America. The film gives you a more nuanced look at why people move. Why would a working-class, Black Cuban family want to leave where this tremendous change had happened, with all kinds of hopes for a more equal society? It’s not like they had riches they were losing because U.S. imperialism was ending in Cuba. When you look at migration in this way, you understand that U.S. policy separated the Fosters from their family.

FN: Something else I found unique and inspiring outside of the content of the film was how it was produced. I’m assuming it was an unintentional cameo, but when you’re visiting your husband’s childhood home, there’s a mirror shot of you holding a small camera and a shotgun mic. When I saw you in the mirror, I was surprised that was all you shot with. Was shooting that way always your plan, or were there financial constraints on production that limited the possibility of a larger production team?

PS: It was out of necessity. It’s a family story. I went to Cuba with my husband and my daughter, who was eight years old then. How could I possibly go with a crew?

FN: It’s so well shot, especially the scene where your husband was at the door of his childhood home. I love that scene. I replayed that one moment when the then-current resident opens the door and kisses your daughter on the cheek. With those handheld cameras, it's hard to prevent shakiness, especially if you’re not trained. But that scene is remarkably natural and stable while you’re walking and following your husband. Was it always your intention to be behind the camera?

PS: I probably benefited from not going to film school. I love big equipment. It’s nice to get the highest kind of production value, but that should never get in the way of story. I came to learn how to do video documentaries with my high school students, with a VHS camera, and we learned together. I was teaching History and creating a curriculum around the Vietnam War, civil wars in Central America, and the struggle against South African apartheid. I would use documentary films as a tool to teach the class. I was definitely influenced by the style of those films shot in Central America—small crews, close-ups.

I had what became the Educational Video Center [a New York City non-profit dedicated to teaching documentary filmmaking to young people] come into the class and do filmmaking workshops. Through that, we were able to get a camera in the school. One thing led to another and I developed a “through our eyes video and history project” where students made films about our local community. You’re able to watch these films on my website, under the “Student Archive” tab. This was my intro to filmmaking. From there, I began to take more workshops and train myself. There was a thriving alternative media community here in New York City back in the ‘90s. I benefited from workshops at Paper Tiger Television and Deep Dish TV.

This decision to be behind the camera was a combination of my resources at the time. This was an intimate family story, and I wanted to be unseen. I wanted the family to be able to have conversations without the camera being a focal point. I shot the film on Hi8, which is the camera I felt most comfortable with. It just felt part of my body.

FN: I’m very interested in the process of this film receiving a 4K restoration, mainly because we hardly see independent, smaller-budget films, let alone documentaries, receive this sort of preservation attention. Was a company interested in restoring this film, or did you take the initiative for its restoration?

PS: I decided to do a restoration when I was already in the process of getting the original footage at The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture’s Moving Image and Recorded Sound archive. The footage would just be disintegrated otherwise. I was thinking of preservation because it’s still an important film, and people today, I guess, expect something sharper.

Robbie Leppzer, a co-member of mine at New Day Films, had been experimenting and working with this software called Topaz, which is an add-on to Premiere. I shot the film on Hi8, and in 2000, everything was transferred to Betacam SP tapes. Those master tapes were re-digitized by Robbie. He would show me footage, and some of the still images looked a bit cartoonish, so it was a back-and-forth to find what looked natural. Some people don’t like 4K at all and think it’s a compromise to bring lower resolution films “up” to a more pristine look. I personally wanted to make the film more relevant. I think showing it in this new form helps with that… You didn’t ask me about the music! [Laughs]

FN: I was just about to! [Laughs] The music is amazing.

PS: There is a group called El Grupo Folklórico Y Experimental Nuevayorquino from the ‘70s. One of their songs is called “Cuba Linda,” which I wanted to be in the soundtrack for the film. When I went to inquire about the licensing, it was a tremendous amount of money. I think $25,000. So that wasn’t an option.

My husband was working at Bronx Lebanon Hospital at that time, with Rene Lopez, who knows a tremendous amount about Latin music and Cuban music, and connected me with Oscar Hernández. Oscar is a pianist and now the leader of the Spanish Harlem Orchestra, and was also part of Grupo Folklórico Y Experimental Nuevayorquino. I called him to help compose the film, and he said yes. He was able to compose things that sounded like “Cuba Linda.” It was such an honor to have him record music for the film.

I also included recorded songs like “Son de Loma” by Trio Matamoros in the scene where the Fidelistas enter Havana. It’s a song that goes back to the war of independence in Cuba against Spain. It goes, “Where are my people, they’re up in the hills.” My husband said that the song was banned on Cuban radio when the Cuban Revolution was happening because it was about overturning colonial powers, and the guerrillas were in the mountains.

FN: What’s next for you and Cuban Roots/Bronx Stories?

PS: I’m working on a film that also touches on Cuba. It’s about my father, who was called before the House of Un-American Activities Committee in the 1960s, which was an anti-Communist Congressional Committee that would subpoena people and get them fired from their jobs. One of the reasons HUAC was interested in attacking my father was that he was part of an organization that led an early trip to Cuba to break the travel ban. In a HUAC hearing transcript, they specifically noted wanting to find out about that very trip. I’m working on a film about his experience before HUAC and how he stood up to that committee. It doesn’t specifically have to do with Cuba except for that little detail.

As for Cuban Roots, I hope it gets used widely in university and community settings. Third World Newsreel distributes it. It’s on Kanopy too. I hope it’s used in a way that continues the struggle against anti-blackness in whatever community and that it can be used to defend the rights of immigrants, especially in this period that we’re in. I hope people can enjoy the music and inspire other filmmakers to make their own films.

Cuban Roots/Bronx Stories: An Afro-Cuban Coming of Age Story screens this evening, September 24, at The Schomburg Center for Black Culture as a part of the series “Black on Screen: A Century of Radical Visual Culture.” Director Pam Sporn and writer Rosed Serran will be in attendance for a Q&A.