As the collective absorption in mass media transitioned from pervasive to absolute in the past fifteen years, the ethics of image consumption have slowly leaked out of the academy into everyday discourse concerning trigger warnings, platforming, and content moderation. The internet is only now realizing some of the promises made in breathless, Clinton-era USA Today features, and we’re struggling through the growing pains as our nervous systems are colonized by infinite stimulation. The great majority of discourse on ethical spectatorship prioritize the dignity of both subjects and viewers as we decide which images are unfit for our hungry optic nerves. Unfortunately, in our audio-visual approximation of Borges’s infinite library, every possible act of misanthropic depravity is always available. Some of the ugliness is quarantined on the dark web, some enjoys evanescent life on YouTube, some gets sanctimonious varnish and the Wolf Blitzer treatment. Examining the production and consumption of horrific documentary imagery has gone from obscure academic study to basic life skill.

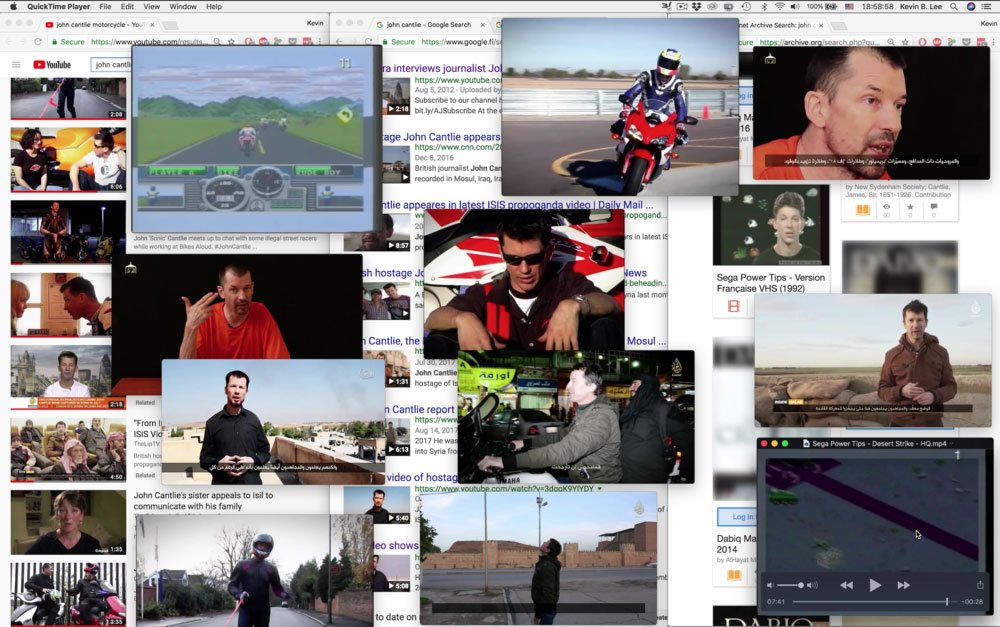

Media theorists Chloé Galibert-Laîné and Kevin B. Lee conduct an intense interrogation of image-making and viewership in their “desktop epistolary” Bottled Songs 1-4 (2020). This too-brief essay/dialogue film is structured as a narrated email exchange illustrated by the desktops, tabs, and windows of the filmmakers as they pull on every loose thread they encounter while investigating the social media content of the West’s most recent bogeyman, the Islamic State. The exchanges begin with YouTube videos before fanning out across a familiar itinerary: Wikipedia, Facebook, the Wayback Machine, Google Images.

Galibert-Laîné begins the exchange by acknowledging her struggle to articulate her intense fascination with a video of ISIS soldiers humiliating a group of prisoners stripped to their underwear during a death march. Tracing her descent into this harrowing k-hole, she considers the various contexts of the video in its online proliferation. YouTube takes down several incarnations posted by smaller accounts but permits a state-financed French aggregator of “citizen journalism” to post the same video without hassle. The same six-minute clip is deemed documentary footage or terrorist propaganda depending on who’s posting. Like 9/11 or George Bush’s “mission accomplished” pageant, the death march was conceived as a media event. The cameras are not passive repositories; instead “they produce images … but they also participate in the torture of the prisoners, reminding them that the spectacle of their humiliation will be shared with the rest of the world.”

Lee’s segments involve a breakdown of editing techniques in a feature-length documentary produced by ISIS as well as an analysis of British reporter John Cantlie’s ambiguous captivity, in which he was either forced to propagandize for ISIS or consciously joined the organization. At every turn both filmmakers consider their responsibility in consuming and disseminating these images. Galibert-Laîné considers herself (and thus presumably millions of YouTube viewers) a “co-producer” of these jihadist videos by virtue of watching them. Their aim isn’t to smugly rid themselves of such complicity in these records of inhumanity, but to work out some of the contours of a photographic regime that implicates us all.

Bottled Songs 1–4 is screening today as part of the Museum of the Moving Image's First Look 20/21 festival.