At the heart of John Huckert’s The Passing (1983) lies a remarkably believable friendship between World War II veterans Leviticus “Rose” Washington (Welton Benjamin Johnson) and Ernie Neuman (James Carroll Plaster), two aging bachelors sharing a crumbling bungalow on the outskirts of town. Rose lies in bed, reading religious and new age texts, and contemplates taking his own life; Ernie makes haphazard stews for their meals and “borrows” a random car for some light shoplifting in town. While consequently locked up for an afternoon, Ernie encounters Wade (played by Huckert), a young man on death row whose execution is mere moments away. In flashbacks, the film traces Wade’s whirlwind romance with bartender Monica, the birth of their child, and the violent, ultimately lethal revenge Wade takes on the mechanic who raped Monica. What connects these men, aside from geography and socio-economic status, is their disposability in the eyes of society. This also makes them ideal subjects of radical experimentation.

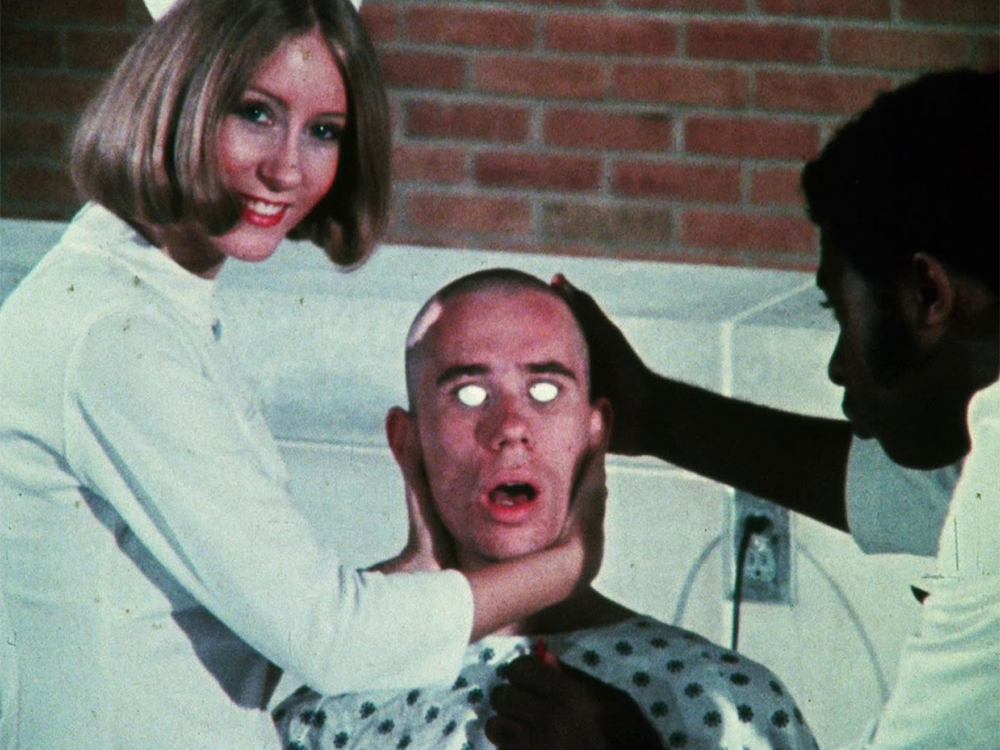

In its final act, The Passing shifts into science fiction, a tonal adjustment barely intimated by the preceding two acts and thereby all the more potent. Already teetering on the threshold of death, Ernie and Wade volunteer for “rejuvenation,” the euphemistic description of a brain-swapping procedure that empties Wade’s body—a process horrifically captured with a pair of stark white contact lenses—to make room for Ernie’s mind, or reincarnated soul. The film is blissfully free of any explanations, scientific or other, opting rather for low-budget psychedelia and the sort of frightened incomprehension shared by its ill-informed protagonists. What matters is rather well summed-up by one of Rose’s final recitations, excerpted loosely from T. S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding”:

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

That is, for all the medical advancements and magic we might muster via scientific exploration, our relationships—whether romantic, as that between Wade and Monica, or platonic, like that of Ernie and Rose, or of any other sort—are truly invaluable, and will be missed the most when sacrificed for progress. Though hardly an original message, it is one well worth a thoroughly entertaining 90 minutes spent exploring, particularly amidst the current atomization, wellness grifting, and age-maxxing that have achieved not only ubiquity but the status of national policy.

The Passing is a superlative example of regional filmmaking. It was written, cast, and filmed on the campus of the University of Maryland, College Park, and its surrounding environs. Huckert’s co-writer and co-producer, Mary Maruca, had been his English professor; cinematographer Richard Chisolm was still a student in the film department at the time; Baltimore’s own John Waters purportedly offered advice on the need for violence and nudity in the film; the real-life friends playing Ernie and Rose were local amateurs. Shot piecemeal on weekends, edited shortly after the death of Plaster, and funded largely with maxed-out credit cards, the film took over seven years to finish. Eventually, it premiered at the USA Film Festival in Dallas, Texas, while Huckert was still in his early 30s, but then it mostly faded from view. As much a genre oddity as an effective meditation on loneliness and love, The Passing is also a treasured testament to its makers’ ingenuity and perseverance.

The Passing screens tonight, January 31, at Spectacle Theater as part of the series “Best of Spectacle 2025.”