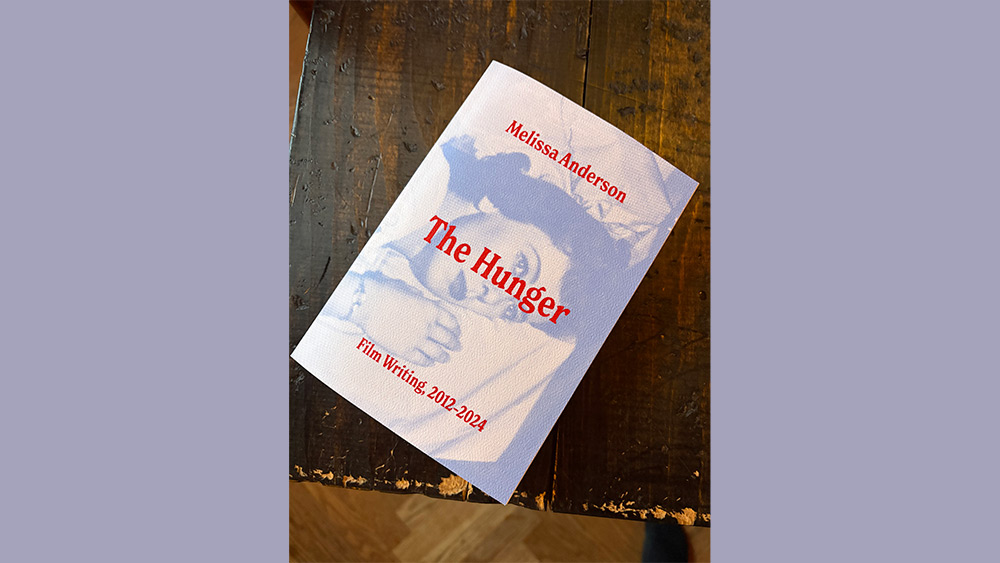

In her first collection of published criticism, The Hunger: Film Writing, 2012–2024, Melissa Anderson advances a delicious selection of reviews and essays on film culture across several decades, from Room at the Top (1958) to The Substance (2024). (Strangely enough, two films about status, ascension, and an “older” and younger woman “taking turns,” so to speak.) Anderson is presently the film editor and lead film critic at 4Columns and was formerly the senior film critic at The Village Voice, where she wrote a column on repertory programming in New York City. In 2021, she penned a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire (2006), sifting the film’s considerations of stardom and Hollywood through its prodigious lead, Laura Dern.

Indeed, Anderson’s writing is enduringly attuned to the “acteurist” dimensions of a film—performance, stardom, comportment, affiliation—and the sensuous/sensual impressions actors leave on the screen. This text, which cheekily borrows its name from the 1983 Tony Scott film, as well as the unslakable cinephilic appetite, is sectioned into four parts: “Looking Back” (repertory offerings), “The Homosexual Agenda and Trans Missions” (the screen, queered), “Cinema, Industrial-Size and Smaller (with a focus on heterosexual depravity),” and “Star Studies” (close readings of actors).

I had the pleasure of speaking with Anderson about theatregoing, today’s “paraprofessional opinionators,” short writing, tall films, and nascent stardom.

Saffron Maeve: I’ve been thinking about the Jacques Rivette observation you quote in the book: “Every film is a documentary of its own making.” Your writing also has this incredible documentary quality where your observations are buffed by rigorous research on the artists as well as personal injection. What is your research process like when you’re penning a review?

Melissa Anderson: If I’m writing about a film that is an adaptation of a novel, I will do my utmost to make sure that I’ve read the source text. Then the research will often be—as it is for many critics—digging more deeply into an actor’s filmography and learning some fascinating bits of trivia—or what one may dismiss as trivia, but which is sometimes the key to unlocking the mystery of a performer.

With La Piscine [1969], I remember investigating a lot about Alain Delon’s rather sordid association with gangster types. I also just have a large trove of facts at my disposal, so while I was watching the film, I was pretty sure that at least one of Jane Birkin’s most popular songs with Serge Gainsbourg came out at that time. So the research will often be going off of some bit of knowledge I already have—things that having an internet connection makes possible.

SM: As the commissioning editor at 4Columns, you’ve assigned yourself several of the pieces which appear in this text. Do you often assign yourself films prior to seeing them or do you undertake assignments after having a strong reaction to a film?

MA: I’m incredibly fortunate at 4Columns that we can cover anything we want and that is often repertory offerings, of which we in New York are blessed every week with a bumper crop. If I’m going through the new releases and am just not finding anything particularly exciting to me, then I will see what’s coming up repertory-wise. There have been a handful of occasions where I’ve assigned myself a new release, then I see it and realize I am so indifferent to the movie and have nothing of interest to say. In this case, I will substitute something else, but that doesn’t happen all that often.

SM: In your conversation with Erika Balsom at the end of the book you make the point that the fundamental duty of the critic is to honor the intensity of her reaction. How does that fare with a middling read of a film? I think Wonder Woman [2017] was one of these.

MA: I wrote about Wonder Woman when I was on staff at The Village Voice, where time was so much more of the essence and deadlines were immovable, so once you committed, that was it. I try to enter every screening room with hope and good faith, but with Wonder Woman, once they leave the woman’s land where they’re cavorting, one becomes increasingly aware of how wooden a performer Gal Gadot is. The challenge is then, how can I make this interesting for myself? More importantly, how can I make this interesting for the reader? So I went back to the idea that if they had just stayed in what I like to think of as a great lesbian separatist compound, it would have been a better experience for all of us.

SM: You mention in the introduction that you omitted your early freelance writing from the book because you found it “excruciating” to revisit. What was the process of rereading and selecting the pieces which make up the book?

MA: I’m sure you’ve also had the destabilizing experience of rereading something that you’ve written. Even when I see my name attached to a piece, there have been moments of total disassociation where I think, who is this person? I had a pretty good hunch when I set about the task of deciding what I would assemble for the book that there would be lots of 4Columns pieces in there, some Artforum and Village Voice, too. With the vague criteria I had of deeming something suitable or not, I’m pleased to say there were a few moments where I was rereading something, chuckled, and thought, okay, that’ll go in. Then there was a second layer of selection thinking [about] which pieces might go well in the four sections I had imagined.

SM: Can you speak a bit about how you chaptered the book? Were those lines of “homosexual agenda” and “heterosexual depravity” quite clear to you from the beginning, or did they develop as you revisited your work?

MA: I’ve spent most of my career as a film critic writing about queer cinema—not exclusively, but a large part of it has been devoted to queer cinema presented in a repertory context. With the subcategory of heterosexual depravity, which was a waggish parenthetical, I wanted to write about several higher-profile films. Things like Wonder Woman or Sofia Coppola’s The Beguiled [2017], which one wouldn’t associate with queer cinema.

SM: Many of your reviews situate the films within the context of your own viewing: Losing Ground [1982] on a whirring old laptop; Play Misty for Me [1971] in a packed crowd at Metrograph; a press screening for Trenque Lauquen [2022] where you were an audience of one. Do you find yourself engaging with films differently in private or in public?

MA: Generally, when I’m writing on something, I insist upon seeing it in a screening room. But the pieces on Losing Ground and Play Misty for Me were written during the first year of Covid lockdown, when New York’s cinemas weren’t open. One of the great things we were able to do at 4Columns was to keep the film column running with a focus on films which meant a lot to the writers and were available online.

I first saw Losing Ground at Lincoln Center in 2015—an incredible moment of discovery—and Play Misty With Me at Metrograph in 2019. I revisited both during those first miserable months of lockdown. There are sentences in those pieces which I wanted to keep as a record of pandemic viewing, where rewatching them was such a balm but was sometimes counteracted by this terrible melancholy of remembering what it’s like to be surrounded by other people.

SM: You also note the influence of critics like Boyd McDonald, who often aired his frustrations with the metrics of conventional film criticism, and you write that today “we are overrun with professional (and paraprofessional) opinionators.” Obviously, pack journalism has always existed, but do you find today’s opinionators to be a consequence of something particular to our times?

MA: I should preface this by saying I’m a woman of a certain age and there are just certain aspects of film culture that I do not participate in at all. Letterboxd. I have never used it. I will never go anywhere near it. Those who do use it, great! I can’t cast aspersions on it as it seems to bring people a lot of joy.

What I’m noticing and what causes some concern is the way a consensus builds around a film so quickly. It’s making critics nervous to not toe the party line, and there isn’t a variety of opinions about hotly anticipated films anymore. Some of it has to do with what publications will run. Some will only run a piece if it’s adulatory or singing something to the high heavens—they do not want to run anything ambivalent or negative.

SM: You’ve previously spoken about your “abject terror of writing anything longer than 3000 words.” This resonates very much with me, so I wonder, is this still the case? What is it about shortform writing that appeals to you?

MA: I’ve been at 4Columns for eight years, where the word count is a thousand, so your writing metabolism adjusts to that. When my editor at Fireflies Press told me the monograph on Inland Empire had to be at least 15,000 words, I remember signing the contract and thinking, “Oh, can I do it?” The way I was able to manage writing something of that length, which seemed insurmountable, was by breaking it into teeny-tiny, mini, bite-sized portions. For a period of about three or four months, I wrote at least 150 words a day—sometimes more, but never less. Then it just builds up momentum from there. So, I have gotten over that terror a tiny bit, but it is still with me.

SM: In your review of New York, New York [1977], you state that Scorsese’s kind of cinema, “films for grown-ups,” are imperiled when posed against the mainstream. How do you, as a critic and an editor, maintain a readership and audienceship that privileges “grown-up” cinema or more marginal works? Do you write for that audience already, or in the hopes of converting people’s tastes?

MA: It’s true—as the person who determines all of the film coverage at 4Columns, I try not to be drunk with power. I’ll need to fact-check this, but we have never run a review of an animated movie. We ran one review of a superhero film, and that was Hanif Abdurraqib on Black Panther [2018]. That film kind of transcended the MCU trappings and I didn’t want it to be a film we ignored. We’re trying to point to films which readers should be seeking out. Most of our readers are in New York, so if I or another film writer extol something that’s playing at Anthology for just a couple of nights, hopefully that will be enough of an encouragement to get somebody to 2nd Avenue to see the film.

SM: The final section of the book is dedicated to “Star Studies,” where you take up the enduring qualities of screen actors and their stardom. Are there any actors you haven’t written about, but whose stardom, present or potential, interests you?

MA: There are pieces in the book about Adèle Haenel and Kristen Stewart who were born just one year apart, in 1989 and 1990, so they are millennial stars. I think Josh O’Connor—who also fits squarely within the millennial generation—is a performer who has really intrigued me, especially in The Mastermind [2025]. His Challengers [2024] co-star, Mike Faist, is also one. I’m not ashamed to admit that Spielberg’s remake of West Side Story [1961] slaps. That movie is incredible. One of the most exhilarating moments watching it was being presented with Mike Faist, who just burned up the screen from his very first moment.

I do not watch much television—I’m very proud to say this—but when I had Covid for the first time in 2022, one of my great pleasures was watching every episode of Euphoria. That was a program I felt had some amazing, charismatic performers, and somebody who truly impressed me was Hunter Schafer. The movies I’ve seen Hunter in have perhaps not used her talents to the utmost, but it’s always exciting to encounter and follow a new performer. To see what these magnetic creatures can do on a large screen, as you just sit there wrapped in the dark.

The Hunger is now out via Film Desk Books. Melissa Anderson will host a screening at Light Industry on December 2 to celebrate the book’s release.