The absurd happenings, bright visuals, and risqué character design present in Wong Ping’s animated work inextricably link his oeuvre to our preeminent social commons: the internet. His videos align with contemporary culture’s fondness for short and affective media: monkeys on skateboards, human pratfalls, hypnotic animations. All of these variations in content represent a new field of attractions that engages emotional impulses rather than narrative absorption for those invested in endless surfing (and now scrolling) online. Wong often plays off of this popular digital media, placing innocent animal cartoons in cruel scenarios to make sharp observations about human behavior.

His work recalls YouTube humor as seen in bizarre but popular videos from the aughts, such as Jason Steele’s Charlie the Unicorn series, which built upon a craze for juxtaposing children’s characters with more severe themes. Similar internet sensations included the surreal puppet show Don’t Hug Me I’m Scared and the strange creations of David Firth. “I live in the internet so I make work there,” Wong has said. His short animations—in which anthropomorphized trees are capable of telepathy and three-headed rabbits can become magistrates—are not only the product of a singularly talented mind with a crude sense of humor, but also an attempt to co-opt the modern web’s collection of strange apolitical content into radical gestures.

Inspired by fabulists like Aesop and the Brothers Grimm, who used myths to comment on the inequities of their respective eras, Wong mines the aesthetic codes and quicksilver narratives of popular internet videos to criticize China’s hostile absorption of his native Hong Kong and the rise of performative activism on social media. Characters like the prideful Inspector Chicken, who finds fame on the internet for overcoming neurological adversities and becoming a police officer, and Cow, an anarchist turned sellout, play out Wong’s own concerns about local politics. The former examines how displaced and distant online adulation can let unknown real-world damage go unchecked, while the latter depicts the Sisyphean struggle of upholding leftist politics under capitalism. Although all of Wong’s work is full of sudden thematic and narrative detours, as well as formal and aesthetic exhibitionism, its ethics are always on full display. Like all fabulists, Wong is a moralist.

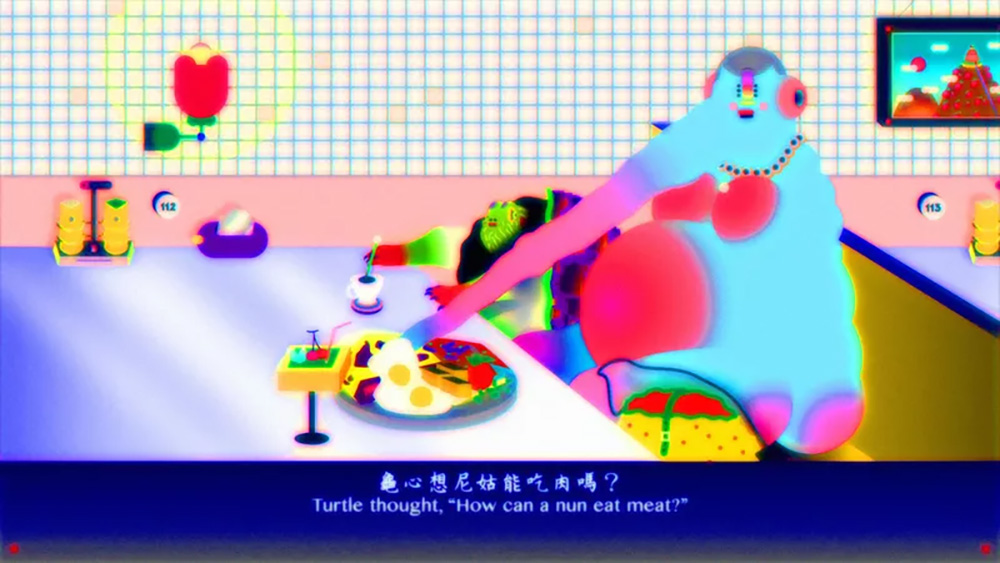

Wong Ping’s Fables 1 and 2 (2018–2019) use small narratives, three to each video, to illustrate moral lessons. Each story unravels in a single frame, brimful of spontaneous disruptions that push the story forward alongside updates provided by an omnipresent narrator with a vocoder lilt. The first entry in Fables 1, titled Elephant Nun, concerns a lovelorn turtle stewing over his breakup with the eponymous mammal. As Turtle sits alone, Wong populates the screen with recollections from his defunct relationship—a karaoke encounter, a quaint stroll, a sudden breakup—as though he were reliving them in real time, haunted by his poor choices. Memory is always manifest in Wong’s stories, whether alluded to or directly represented, to fill in how each of his characters achieved greatness or became crestfallen. Whatever life Wong’s characters have had, or whichever historic moment he is commenting on, there’s always a punchy adage at the end, a lone kicker on a simpler screen that invites pondering apart from the noisy and polychromatic vignette preceding it.

The Modern Way to Shower (2019) is framed vertically, as though a screen-recording straight from Wong’s smartphone. Wong answers emails, texts, and abruptly joins a private webcam session where he’s arranged for Ruby, a woman in a full latex bodysuit, to be showered. He wants the sub to be washed with the same “ice-blue” water as that used by cops against activists during the Anti-Extradition protests that took place in Hong Kong in 2019 and 2020. Instead, the dom in charge of showering Ruby engages in violent play, and Wong flees to other apps in frustration, occasionally returning to text the service’s moderator to be gentler and “tickle Ruby” because he wants to see her “laugh and [be] happy.” Right before his phone dies, he asks the moderator, “How could people jerk off by watching this?”

This bewilderment around how people pleasure themselves continues in Sorry for the late reply (2021). A stand-in for Wong that looks like two twinkies glued together atop a pair of legs becomes obsessed with a flash of blue produced by lightning during a thunderstorm. His fascination leads him to first massage and then violently prod a woman with varicose veins in her thighs, hoping the punctures release her blue twisted veins out into the world like lightning bolts. Instead, the jabbing fires back and sucks him into an Innerspace-style adventure inside the woman’s body. Wong investigates the far reaches of his desires, living vicariously through his character’s fantasies to develop insights into his own kinks.

In Crumbling Earwax (2022), a muscular sage asks his girlfriend’s asshole whether he should quit his job. The video is fashioned as a triptych, the center panel featuring the sage’s stressed forehead as the lateral panels display circular views of anuses inside earholes. The composition evokes a Medieval altarpiece, accenting Wong’s tendency to irreverently update traditional frameworks and story forms. The lateral panels’ content, featuring layered, void-like holes, are a signature of Wong’s style. His baroque frames defy cinema’s typical movement across time by placing multiple asynchronous stories within one frame, much in the same way digital screens become overstuffed with frivolous scenes of life that privilege nowness in such a way that the future is rendered fictional.

In the 8-minute short The Other Side, a man decides to leave his mother’s womb and wanders a labyrinth of turnstiles until he reaches a vulva patrolled by two guards who deny him access. Soon, he begins yearning for home and tries making his way back into his mother’s womb in a state of defeat. Dawdling about, he finds himself lonesome and longing. Perhaps this is what it means to live and work in the internet? The protagonist’s lonely musings might as well be the thoughts that run through one’s mind while web surfing. “People here are just like me,” he says. “I think I’m leading a meaningful life, but it’s actually more or less the same on the other side.” Absorbed in the many sights beyond his shelter, he feels numb.

This disappointment with the world around him is characteristic of a shared acknowledgement that the internet is unruly and exhausting, rife with so much content that everything registers as trivial. Life’s entropy overshadows its small joys and glimmers of hope; the same is true in the digital dimension.

“Wong Ping: Between Desire and Isolation” runs July 14–15 at Metrograph. The film The Other Side will play on a continuous loop in the theater’s lobby through July 28.