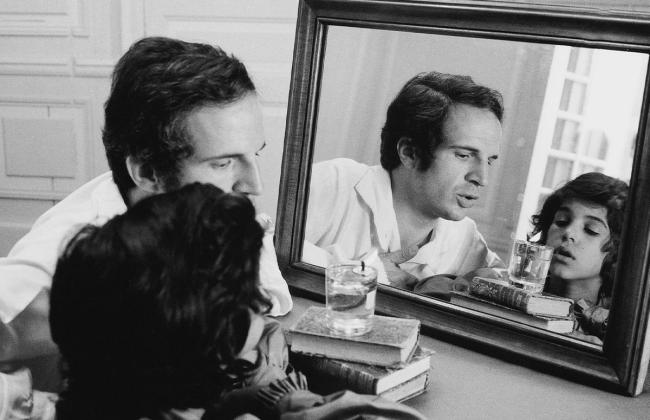

The subject is one to which François Truffaut would return repeatedly: in Les Mistons (1957), his first short; in The 400 Blows (1959), his debut feature; and in A Beautiful Girl Like Me (1972), an underrated comedy starring Bernadette Lafont. But the changes in his personal life—a decade of success and international celebrity, and perhaps also becoming a father himself—found Truffaut in a different position when making The Wild Child (1970). By the end of Stolen Kisses (1968), his alter-ego, Antoine Doinel, completed his transformation from troubled delinquent to a comic bourgeois character. And Truffaut, appearing here before the camera for the first time in one of his own films, no longer represents himself as a “wild child,” but rather in the role of a teacher and psychologist.

More than his other films, I would argue that the integral point of reference for Wild Child might be Maurice Pialat’s debut film, Naked Childhood (1968), which Truffaut co-produced under his company Les Films du Carrosse. The sobriety and psychological intensity of Pialat’s film anticipates the pivot in Truffaut’s own style here, fully shedding the flashy aesthetic of the early nouvelle vague period. What’s more, Pialat had already made explicit the connection between the topic of adolescent delinquency and the protests of students and workers that engulfed the world in ’68.

Truffaut’s film—an adaptation of a famous 18th century case study of a child discovered in the woods having lived his first decade without human contact—makes no such connection. But its inquiry into the origin of language and the relationship between psychology and authority bear the mark of the same environment in which the philosophies of Louis Althusser, Michel Foucault, Jacques Lacan, and Jacques Derrida would flourish. Moreover, its study of language as a sign system places it in an otherwise unlikely dialogue with films by Jean-Luc Godard at the end of the decade, in particular Six fois deux / Sur et sous la communication (1979).

Truffaut often voiced his disinterest in politics, and seldom attempted making political films. Then again, perhaps he let his cards show in his own way. One might point to, for example, the fact that he opens this film with a kind of reimagining of the hunting scene from Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game (1939)—a key film for him both cinematically and politically—as the local gendarmes use bloodhounds to track the child in the forest. For Renoir, this scene conveyed the total moral decadence of the European ruling classes on the brink of World War II. Here, the symmetry of the barking dogs, trained to kill, and the child scrambling in the trees sets a tone for the remainder of the film: that cruelty, rather than something that emerges from nature, is just as much a consequence of teaching as it is morality.

The Wild Child screens this Saturday, February 7, at BAMPFA on 35mm as part of the series “Laura Truffaut on François Truffaut.” Laura Truffaut will be in attendance for a post-screening conversation with Koret Visiting Professor Aner Preminger.