In 2001, just over a decade into Romania’s post-communist rebrand, the country’s tourism board announced plans for a Dracula-themed amusement park in Sighișoara, the Transylvanian hometown of Vlad Țepeș—15th-century warlord of the principality of Wallachia, brutal “impaler” of regional renown, and purported basis for Bram Stoker’s fictional count. The project was controversial for, among other reasons, linking Romania’s ostensibly noble past to a foreign-invented fictional character, but the far greater scandal came when the project was abandoned, leaving in the lurch some 13,000 citizens who had been lured and manipulated into purchasing shares in “Dracula Park.” After all, as Sighișoara’s mayor had been quoted as saying: “Everyone else makes money from Dracula. Why shouldn't we?”

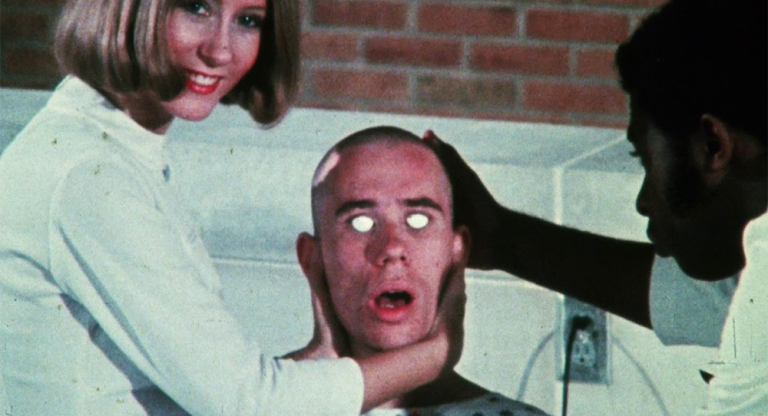

A bone-deep awareness of such national pathologies and complexes, and the opportunities they present to scammers and opportunists, underlies Radu Jude’s gleefully heretical new revue, Dracula. Packaged as a series of fragments offering a dozen or so variations on the vampiric theme, Jude’s second feature of 2025 (following the no less incisive, if way quieter Kontinental ’25) unspools via an intentionally crude frame story in which a frustrated film director (Adonis Tanța) seeks to improve his own Dracula movie’s popular and international appeal by use of a bespoke but very janky AI-system named, naturally, Dr. AI JUDEX 0.0. The film we see, a 170-minute stream of bonkers riffs on Romania’s most complicated celebrity export, is the result.

I spoke with Jude via Zoom from France, where he’s been shooting a new film.

Mark Iosifescu: I want to get to some of the questions of nationalism that I think permeate this film, but first I think we have to talk a little bit about the same thing everyone wants to talk to you about: AI.

Radu Jude: Americans are obsessed with that. I didn’t realize it would be such a big issue.

MI: It’s so interesting to hear you say that, because it seems, to me, that Romania also has had this very specifically tangled history with internet technology. For a long time, the country was considered a hub of hacking and cybercrime, and then it also became known for its more legit tech and IT industry, especially in Transylvania. More recently, of course, there’s the saga of the country’s last presidential election, which was destabilized by an influence campaign on TikTok.

RJ: What I can say—as someone who works in arts, cinema, culture, you name it—I think the internet was [Romania’s] salvation from total provincialism. After the revolution, and even after joining the EU, although there was much more connection with the outside world, the country is still very isolated, from a cultural and institutional point of view. For instance, if you need a book, the only solution for some of the theoretical books—since they aren’t translated, and you can’t find them in bookshops in Romania—is to pirate them. So the internet, for me, was hugely important, and still is. I know PhD theses which were possible only because the authors had access to pirated books. Now, of course, the internet and platforms like TikTok can be used in many ways, can be abused in many ways, and sometimes that happens.

Regarding AI, that’s another thing. The way I used it, first of all, was to experiment, to see how it can be of any help—what are the aesthetics, what are the strategies you can use—and also, from an economical point of view. Since the Romanian film industry doesn’t really exist, there are no high stakes. People don’t say, “Oh, we’re gonna lose billions of dollars if AI takes over.” It’s nothing; it’s just a few people who make films with budgets that wouldn’t even be enough for catering on a regular American film. So there are no stakes, and that’s why I think there’s a difference in attitude. For me, it was just a tool to be able to finish the movie. But for many people in the United States it seems to be the crucial issue of today.

MI: Still, I think there’s a clear sensibility in the way AI shows up in Dracula. You could have chosen to use it in a different way, one that’s probably closer to what its creators intended. It’s similar to your use of iPhones to shoot this and Kontinental ’25, or really, any of these tools that have an extractive, privacy/surveillance/data-harvesting element. It seems crucial that you employ them in a vernacular mode. It also feels related to the explorations of labor in many of your films, and in particular in Dracula’s incredible “Das Kapital” segment.

RJ: I’m interested in and a big fan of TikTok videos. I even did, with Andrei Rus, who’s a film theorist from Romania, a compilation of TikTok videos [Little Poems in Prose, which screened at this year’s NYFF].

MI: I was at that screening. It was great.

RJ: I’m happy you saw it. You could think that these people really use these tools, which are considered “amateur,” with much more creativity than professional filmmakers. And also AI. There’s a lot of AI used now in a vernacular way by people doing memes, or small videos. Sometimes—most of the time, like everything—it’s not interesting. But sometimes it’s really, really striking.

MI: I’m also curious about this kind of potential, the—without being too lofty about it—radical potential of memes and nonsense. I’ve heard you speak about the concept of bășcălie, a kind of aggressive mocking humor that is perhaps characteristically Romanian. It seems like this kind of absurdity and subversiveness is something pretty germane to your work.

RJ: Yes, for sure. I have to choose my words carefully, because this can always be interpreted badly. When you say something is Romanian, what does it mean? I think it’s true that there’s a culture, in the biggest sense of the word. A culture of human and social interaction that creates a difference between how Romanians interact and how Japanese or Americans interact. There’s a lot of creativity in this mocking humor, which you find in literature, on the internet, on TikTok. I think my films were fed from this soil, whether I want to admit it or not.

Sometimes I’m not even aware [of it] until [I see] a reaction from abroad. For instance, in this film, the thing about the so-called “vulgarity.” Another issue that I saw with American and Western European film critics. They were really against the film because they’d say, “It’s so vulgar.” But in a way, from the kind of internet culture I’m observing, in Romania at least, it’s not vulgar at all. It’s very mild.

MI: I think it’s also true that, in the States, unless you’re being willfully prudish or very hypocritical, it’s obvious that our cultural and political discourse is extremely vulgarized.

RJ: Donald Trump is quite striking. If he wasn’t the President of the United States—well, then he wouldn’t be who he is—but it’s quite striking that he has the same kind of humor as Romanian TikTokers. I mean, that video of him throwing shit at the protestors from a plane… In a way, it would be great, if he weren’t who he is.

MI: Right, which gets us to the darker side, to how these technological spaces can also be breeding grounds for really fucked-up nationalisms, as way too much recent history has shown, and which this movie doesn’t shy away from calling out, including in the end credits. I’m curious what it felt like to reappropriate a traditionally nationalist Romanian symbol like Vlad the Impaler, who has shown up in some of these techno-fascist spaces as well.

RJ: It’s one of the issues of our country: this nationalism that basically never went away. You had it in the ‘20s and ‘30s in fascism, which ended in the terrible fascist dictatorship of Marshal Antonescu, who brought Romania into the war on Hitler’s side and took part in massacres and genocide against Jews and Roma. And then, in the communist dictatorship, especially under Ceaușescu. It was, again, heavily nationalistic, mixing ideas and tropes from the fascist times with some Marxist flavor.

Romania, because of its historical position and its geographical position, was always between East and West, between Russia and Western Europe. Who are we? Was always an ontological question. Europe and the West always meant freedom, free markets, and democracy. So half of the people, or more, depending on the times, were always [looking] towards the West for these values. And then, all of a sudden, things became very, very murky, because all of a sudden, the West, especially the United States, didn’t have the same values. So now people say, “OK, let’s embrace Western values. For instance, Trumpism!” And we—I include myself—who supported the other values don’t know how to react.

Since we are a small country, a new country in this place between East and West, we’ve always needed models. Who is the model now? That’s the thing. Because if you say it’s France, or Germany, well, these countries also have a far right which is taking over. So it becomes very complicated. But it’s true that I created this character, a mix of Vlad the Impaler and Dracula, and exactly after I finished shooting, it was the start of the political campaign, and the AUR party, the fascist party, used Vlad the Impaler as their icon.

MI: I was curious if the election was concurrent with the production, or if it took place after.

RJ: It was after. At first, I was happy about my intuition, but then it felt disturbing.

MI: There is obviously also a very long history in Romania of people framing Vlad as this kind of national savior, which you cite many examples of in the film: a poem by [Mihai] Eminescu, Romania’s 19th-century poet laureate, in the “Dracula TikTok” segment; the 1979 Vlad Țepeș film by Doru Năstase, which you include excerpts from; and a kind of prayer-poem in the film’s final segment, recited by a young girl. Many centuries, basically, of people being like, “Vlad, come back, your country needs you.”

RJ: Yeah, it’s already a tradition. He’s a figure who, for me, is a very obvious proto-Hitler, a proto-fascist. But since you cannot have the same kind of open admiration for real fascist figures like Hitler, like Mussolini, like Marshal Antonescu, you can have it for Vlad the Impaler. And that makes it okay for many people, but it’s as disturbing as if it would be Hitler, for me.

MI: It’s maybe also tempting for someone in the West to think of this tendency as a very Romanian thing, but it’s actually a kind of reactionary, nationalist nostalgia that people in the United States now understand very well. A friend of mine saw Dracula and said, “We all live in Romania.”

RJ: [Laughs]. I will repeat that, from now on.

MI: Yeah, and because of that, it’s really hard for me not to try to read the whole movie through this lens of national myth. But it’s also about many other things, obviously.

RJ: Yeah, but this national grounding is a big part of it. Not everything is around nationalism, but it’s a very local film, in a way. Because, first of all, engaging with such a myth, with a character who was depicted a million times, with a million times more money, by great artists all over the world in cinema and literature and whatnot… I said, "Well, what can I offer?” I’m gonna offer something that no one else can. I mean, Coppola couldn’t offer what I did, and thank God for him, he didn’t even try [Laughs].

MI: I did want to ask about the wide cultural net this film casts by using a figure as well-known as Dracula. Your work often contains meta-commentary on film history. You’re referencing Coppola, Murnau, Herzog, Hammer Films, everybody.

RJ: Yeah, but always from a local perspective. The Coppola film is only mentioned because we saw it when we were in high school; it was one of the few Hollywood films that was directly on our screens at the same time as all over Europe. I went to see it. And I still like the film, a lot, actually. But what stayed with us the most was the fact that that film had two lines of Romanian language in it, which are really badly pronounced by Gary Oldman. Now I can understand why. Because they said, “Well, who gives a shit about what Romanians will think about our pronunciation?” [Laughs]. But we saw it, and we said “Why do they pronounce it like that?” It stayed, like a running joke among us for years, saying these lines: “Tu ești dragostea vieții mele…” with a very, very strong British accent. That’s why I said I had to do something around this scene, because it’s the scene that really impressed me, and stayed with me for 30 years.

MI: We also see this local perspective in the film’s discussion of Dracula tourism. This kind of tension in the local culture around leveraging the Dracula myth. I know that, for instance, during the Ceaușescu era, it was unacceptable to connect Vlad Țepeș with the fictional character of Count Dracula. And now, after communism, this idea of embracing Dracula is still quite complicated and controversial.

RJ: True. One of the possible other stories I wanted to tell in the film was about a guy who worked in the hotel industry in Ceaușescu’s times. At some point, he said to the authorities, “You know, I see many people coming to Transylvania to follow the traces of Count Dracula from Bram Stoker’s novel.” So, he said, “Let me do it for the foreign tourists; we’ll take their money and instead, offer them a nationalism class. We’ll lecture them about how Dracula is a Western invention, and that we had our great hero, Vlad the Impaler.” And they let him do that. And of course, being in touch with so many rich tourists or whatever, he started to get some connections, and get some money, and then, after the revolution, he privatized this state tour. He made his own private company and became a millionaire. I think this story tells it all, in a certain way.

Dracula runs October 29-November 5 at IFC Center.