Tom Cruise became a household name during Reagan’s first term, as New Hollywood’s golden age of antiheros and dropouts was gradually drowned out by steroidal Cold Warriors and suspendered financiers. During this transitional period, the young Cruise was able to hone his craft alongside Paul Newman (The Color of Money, 1986) and Dustin Hoffman (Rain Man, 1988) while learning the biz from the likes of Jerry Bruckheimer and Don Simpson (Top Gun, 1986; Days of Thunder, 1990). The meticulous balance between art and commerce that he maintained until the mid-2000s earned him critical hosannas and ungodly wealth. Hopes that he might eventually age out of action stardom and settle into the director’s chair like Clint Eastwood, or let his midsection soften in talky character roles, couldn’t have accounted for his utter refusal to cooperate with father time. Now, at 62, an age when John Wayne won an Oscar for playing declining gunslinger Rooster Cogburn, and both Errol Flynn and Gary Cooper were dead, Cruise commands a stable of competent supplicants to keep the gears of production turning while he dangles from biplanes without a gray hair on his head. Viewed one way, it’s a travesty of talent and curiosity pitifully sacrificed at the altar of vigor. But according to Cruise, parachuting off of motorcycles at an AARP-qualifying age is a testament to the perfectibility of the human specimen, a depressing sentiment echoed everywhere from Silicon Valley boardrooms to Cialis commercials. You can’t say he hasn’t kept up with the times.

“Tom Cruise, Above and Beyond,” the two-month retrospective of Cruise’s films at the Museum of the Moving Image, is a timely reintroduction to the star’s resume. With few omissions, the series presents the creative and financial milestones of his career, beginning with The Outsiders (1983) and stretching all the way to Top Gun: Maverick (2022). The MoMI series makes an unimpeachable case for Cruise’s talent as an actor, as well as his troubling yet deeply satisfying embodiment of messianic spectacle. Key to movie stardom, as distinct from a successful career as a film actor, is the dance between the throughline and its variations. The struggling entrepreneur of Cocktail (1988), whose dream to franchise NYC dive bars in strip malls across middle America is as nauseating as it is financially sound, seems indistinguishable from the gorgeous comer who plays him. Lestat of Interview with the Vampire (1994), on the other hand, curdles the star’s patented swagger into malevolent seduction.

An itinerant childhood and abusive father forged in Cruise a desperation to win friends and influence people. He was the fatherless pipsqueak from elsewhere, pathologically driven by spite to humble all doubters. He transcended a lack of talent in sports by outhustling his peers, a strategy he’s never abandoned. As a perpetual outsider growing up, he studied the behavior of his peers and in so doing honed a charisma that expanded like a tumor until it was capable of mesmerizing a significant percentage of humanity. His notoriously toothy smile is at once ingratiating and threatening, so desperate and unnatural that it inspires pity. (Mary Harron claims his combination of vacant eyes and ravenous amity inspired Christian Bale’s performance as Patrick Bateman in 2002’s American Psycho.) But in cinema’s uncanny valley of ersatz emotion, Tom Cruise’s terrier intensity subdues your reservations until you're eagerly basking in the radiance of that smile. His great asset is the narcissist’s weapon: an ability to instill in others the desire to please him. Pleasing him pleases us, which pleases him in turn, and the cycle goes on, with all participants satisfied by the arrangement. He has a serial killer’s charm, as depthless as a saloon façade on Spahn ranch, but at the movies submitting to Cruise’s smile is just one more delirious suspension of disbelief.

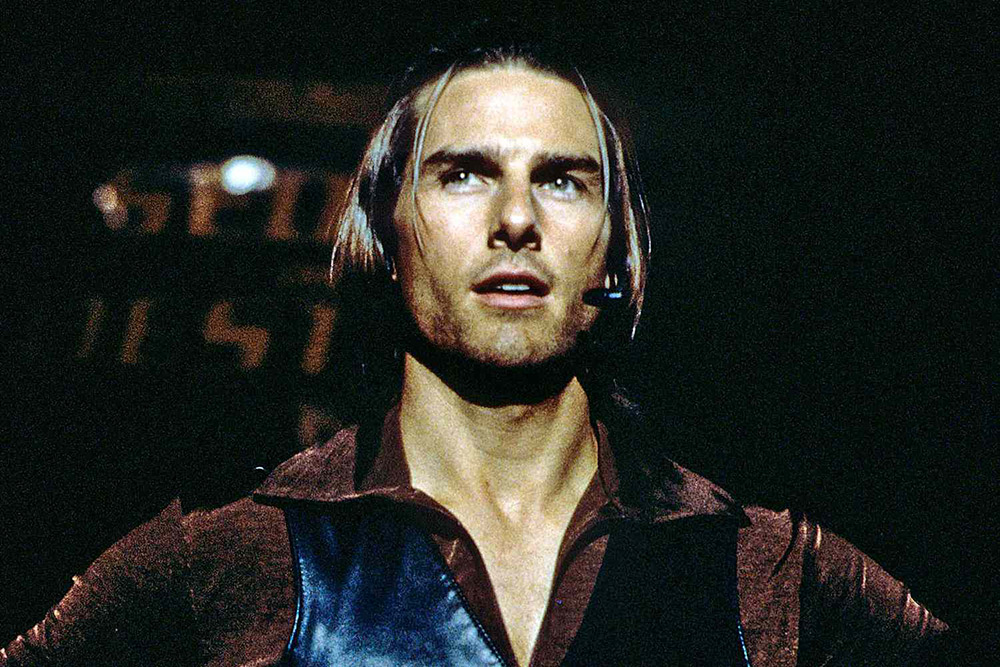

His best work is shaped by filmmakers who force him to wrestle with these chilling aspects of his persona. In Magnolia (1999) he plays Frank T.J. Mackey, a self-help guru who instructs incels “how to fake like you are nice and caring” in order to seduce women. He breaks down at the deathbed of his absentee father after an interviewer exposes his fraudulent past. He’s a bad dad himself in Spielberg’s harrowing War of the Worlds (2005), having skated by on his looks and glib charm until Martians compel him to finally take care of his children. Paul Newman’s legendary pool shark in The Color of Money praises Cruise’s neophyte Vincent as “an incredible flake” blessed with a natural charisma that, once honed, he can use to fleece unsuspecting marks. Another Vincent, in Michael Mann’s Collateral (2004), flatters then torments a hapless cab driver while executing murder-for-hire jobs. His white wig in the latter film uncharacteristically acknowledges the aging process; perhaps not coincidentally the film is also the only time he has played an outright villain.

A Tom Cruise character is never still unless the plot is momentarily baiting us into thinking he’s dead. Unsurprisingly, his least kinetic performance, as a Republican senator in Robert Redford’s middling Lions for Lambs (2007), is missing from the series. There’s an intense physicality to even his most thoughtful performances. Mackey humps the air during his lectures and later does a somersault in his underwear backstage. The pool hustler Vincent theatrically wields the cue like a sword and a microphone between perfect shots. As Dr. Bill Harford, Cruise is so overcome with jealousy while contemplating his wife’s sexual fantasies that he violently claps his hands together in the middle of the sidewalk in Eyes Wide Shut (1999). The moment shouldn’t feel seismic, but Cruise channels a horrifying amount of resentment and shame into the brief gesture. As a wounded Vietnam veteran, he’s in a wheelchair for much of Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July (1989) raging against his trapped vitality.

Interrogations of his arrogance have been sidelined in recent years to bits of comic relief that undermine for fleeting moments the martial competence that undergirds the 21st-century iteration of his persona. Edge of Tomorrow (2014), one of his better action films, works so well because his character develops from a smooth-talking worm to a war hero only after exhaustive—and legitimately funny—trial and error, thanks to a Groundhog Day-like time-loop device. But in recent years, audiences have generally been asked to accept Tom Cruise’s charisma at face value while he’s busy thwarting armageddon. His physical dedication puts him in league with the great athletes of cinema like Harold Lloyd, Jackie Chan and Johnny Knoxville. And as impressive as it is to hold one’s breath underwater for three minutes, we can’t help but long for the days when he considered untangling the ambiguities of human experience, including his own bottomless need for valor, a worthy pursuit.

Tom Cruise, Above and Beyond runs through August 17 at the Museum of the Moving Image.