The first program of “Rotating Signals: The Contemporary Korean Avant-Garde,” a screening series that has toured the United States since July, opens with a 16mm black-and-white silent film by Heehyun Choi titled A Dark Room (2025). Using text from the 18th century Korean philosopher and poet Chông Yagyong’s On Viewing Paintings from the Dark Chamber, Heehyun’s film places images of a projector, lenses, and a film reel alongside images of hands sewing, street traffic, the sky, and tea being poured. These mechanical and poetic images combined with Yagyong’s writing invoke film and painting’s shared ability to create visual expansiveness—like in the calligraphic brushwork of East Asian painting—using small, material means. In the context of Heehyun’s film, the “dark room” that Yagyong writes about is understood as the world inside the projector and, by presenting a silk bojagi as a stand in for a movie screen, the darkened theater, respectively. It’s a work of gentle and elegant clarity about the nature and possibilities of the medium conveyed using specific Korean referents that provides the perfect introduction for the films to come.

The two programs that make up “Rotating Signals” are indebted to the filmmaker Lee Jangwook and SPACE CELL, a screening space and film workshop that he founded in Seoul in 2004. After Jangwook’s film surface on memory, memory on surface (1999) played the Seoul Independent Film Festival and was met with an unfavorable response, he opened SPACE CELL to help provide greater education about experimental film in the city. SPACE CELL became an important resource for 16mm filmmakers, including those featured in both programs, as a site that offers both film equipment and a screening space. Jangwook’s own work on 16mm is often hand-operated and explores the affinities between cinema and memory. These ephemeral and materialist concerns—the intersection of mechanistic illusion, memory, and poetry—inspire many of the films in the two programs. The program is named after Chae Yu’s film Rotating Signals (2025), which is itself a cacophony of images and sounds that seem to pass through the filmmaker’s mind during a train ride through the American midwest. The film is a reconstruction of the chaos of thought and remembrance. Compared with Heehyun’s opening film, Yu’s film is more overwhelming, with an avalanche of imagery and an avant-garde, jazz-inflected score. In spite of their aesthetic diversity, all of the films in the series display an exceptional mastery of photography and formal dexterity, often employing a myriad of cinematic techniques, including tracking shots, optical printing, and impressive superimpositions.

Perhaps one of the most striking and meaningful instances of superimposition is present in Hyoin Kwok’s Spoken Word (2023). The silent black-and-white 16mm film is dominated by an aged woman’s face, but the image that makes the biggest impression in the film is that of an open laptop. A video plays on the computer’s screen, and the filmmaker superimposes flowing water to create a new image, one that unites the idea of flow in nature and technology. Hyeisoo Kim and Luuk Schröder’s Long Sand and Water (2023) similarly finds harmony between the natural and constructed world, intercutting images of a woman peacefully floating down a stream with urban images of rain-flooded streets. It’s this candor and open-mindedness about the everyday world,how we can capture it and possibly understand it, that gives many of the films in “Rotating Signals” a special character.

The final film in the second program, Chool woong-Jang’s Lord (2024), satisfyingly rhymes with Heehyun’s film, continuing A Dark Room’s explicit reckoning with the medium—although, with a greater sense of mystery. We see a hand in frame holding a red string that appears to be slowly moving the camera. There is a physicality to the images, a concreteness to the lagging imprecision of its movement. Despite the feeling of the camera’s heavy presence, the images it captures are dark and romantic—the edifice of a medieval structure, a European oil painting, shadows in the forest. Like A Dark Room, Lord is a present tense film that uses elements of the past to help us think about the realities and history of image-making. When we see a crude stone window framing dense trees beyond, or figures in a painting with a seemingly distant background achieved using perspective, or a large wall that resembles a curved movie screen, the filmmaking apparatus is reflexively acknowledged through images that succeed in maintaining their own idiosyncratic, mesmeric beauty. It all adds up to something esoteric and intimately personal, a sometimes overlooked aspect of great structuralist films. This is one of the most important and daring paths avant-garde film can take: the mingling of reality with poetry until the distinction disappears.

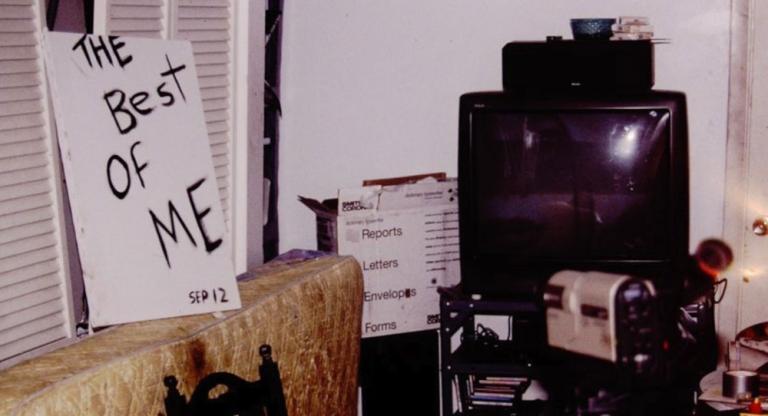

“Rotating Signals: The Contemporary Korean Avant-Garde” screens on Friday, September 12, at Shapeshifters Cinema.