Dorothy can’t sleep. When Walter Murch’s Return to Oz (1985) picks up on the little Kansan girl’s adventures, “it’s been six months since the tornado and Dorothy hasn’t been herself since.” The home she yearned for on the yellow brick road is a let-down, plagued by mortgages, loneliness, crummy weather, and adults for whom all fantasy is pathology. So Dorothy submits to waking dreams of Oz. She earnestly seeks some portal back to that magical elsewhere, the thought of which is the only thing that makes grim reality bearable.

And return she does, though she finds that the fairy-tale land isn’t quite how she left it. “I don’t remember that!” Dorothy repeats, as will many viewers. Strange new creatures run amok in the Emerald City; Judy Garland never encountered the Wheelers—shrieking, clownish, four-wheeled furies—right? Faced with the overwhelming iconicity of M-G-M’s The Wizard of Oz (1939), Murch took the only sensible approach for his sequel: ignore its predecessor almost entirely. The swooning songs, sticky wholesomeness, and candy-colored aesthetics of the 1939 classic are nowhere to be found in the Return, which opts for something altogether weirder, darker, and denser. The movie owes far more to L. Frank Baum’s children’s storybooks than to the M-G-M film. Beat by beat, it’s a strikingly faithful adaptation of Ozma of Oz (1907), the third of Baum’s 14 Oz books. The mechanical soldier Tik-Tok who “does everything but live”; Fairuza Balk’s unflappable, pre-adolescent Dorothy; and the straight-talking Kansas hen Billina, all come straight from the page (among his many personal eccentricities, Baum adored chickens). But where Baum’s tendency was to quickly neutralize threats, Return to Oz lets danger linger. The movie’s perils aren’t temporary aberrations, but signs of the world’s cruelty. One of Dorothy’s climactic triumphs is the result of pure chance. Even in Oz, happy endings are nothing more than a lucky break.

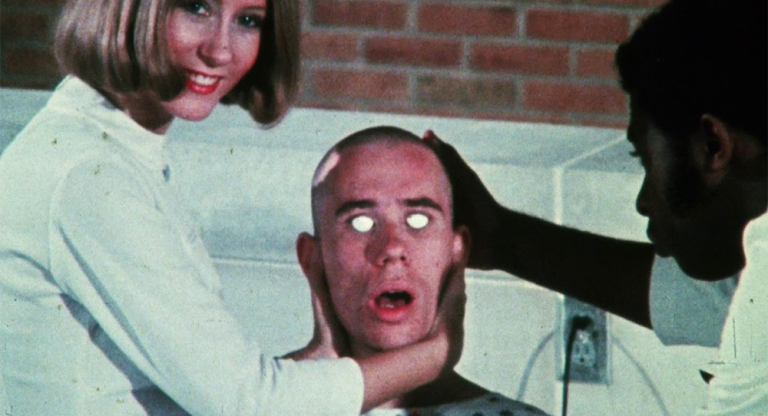

Not long after landing in Oz, Murch draws us into a gilded boudoir lined with glass cases. Here, the avaricious Queen Mombi displays dozens of beautiful women’s heads that she mounts on her neck according to her fancy. In his book Land of Desire (1993), the scholar William Leach interprets Baum’s turn-of-the-century fairytales as expressions of spectacular consumer capitalism that was then exploding across the United States. Mombi’s mesmeric dressing room recalls the design of an early 1900s department store, where the glassy illusion of an endless variety of goods stoked shoppers’ desires and promised perpetual self-renewal. The scene’s magic, alternately seductive and horrific, taps into what the scholar Tom Gunning terms the “cinema of attractions,” early cinema’s disregard for narrative in favor of sharp moments of pleasurable astonishment. Mombi handles her heads with more elegance than Georges Méliès does in The Four Troublesome Heads (1898), but the scintillating effect is one and the same.

Return to Oz screens tonight, December 8, at Nitehawk Williamsburg on 35mm as part of the series “Video Store Gems.”