Anthology Film Archives is among the few American venues celebrating Konrad Wolf’s centennial. Born to a prominent Jewish family in southwestern Germany, Wolf grew up in exile in Moscow after his father fled Nazi persecution for his anti-fascist activism. In 1942, at the age of 17, Wolf enlisted in the Red Army. He served as a translator during interrogations of German POWs, and then as a propaganda officer translating Russian leaflets into German and Allied messages into Russian. He delivered loudspeaker appeals urging Nazi soldiers to defect and witnessed the battles for Warsaw, the liberation of Sachsenhausen, and the final assault on Berlin. After the war, Wolf worked in the Soviet Military Administration’s Department of Culture and Censorship, where he screened old UFA films to determine their eligibility for theatrical release.

At 24, Wolf enrolled at Moscow’s All-Union State of Institute of Cinematography (now known as the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography), alma mater to Kira Muratova, Sergei Parajanov, Andrei Tarkovsky, and countless other Soviet filmmakers. Three years later, Wolf was appointed to the Arts Council of DEFA-Studio, the GDR's state-owned filmmaking apparatus. Every one of Wolf’s films was produced there, and he remains among the studio’s most revered directors. (That Wolf’s brother later became the second-highest official in the Stasi, East Germany’s secret police, is its own fascinating footnote.)

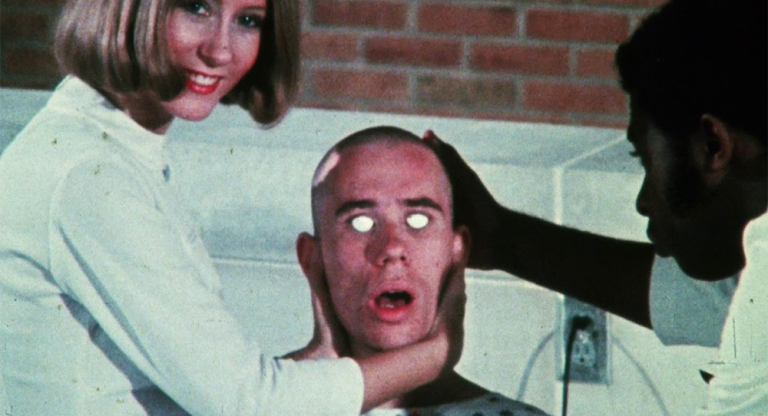

Divided Heaven (1964) adapts the novel of the same name by Christa Wolf (no relation), which was published just a year earlier. The story traces the months leading up to the construction of the Berlin Wall through two doomed lovers: Rita (Renate Blume), young and idealistic, and Manfred (Eberhard Esche), an older chemist increasingly disillusioned with life in the GDR. Her parents have already “returned” to the West, and its lure lingers throughout the film.

Despite working behind the Iron Curtain, Wolf’s film resembles the work of western contemporaries. His style fuses the epic pictorialism of Soviet masters like Mikhail Kalatozov with the disorienting ambiguity of Alain Resnais and the wintry restraint of mid-sixties Godard. (A Married Woman and Band of Outsiders were released the same year as Divided Heaven.) Dutch angles and a densely composed mise-en-scène exploit the graphic possibilities of the widescreen frame to striking effect.

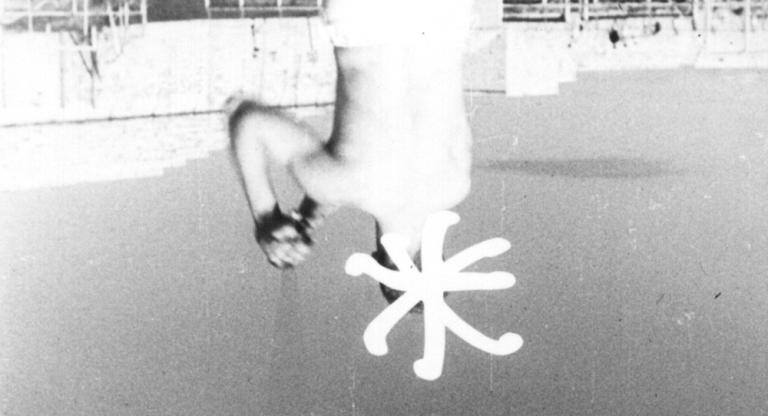

Divided Heaven unfolds as a nonlinear memory film, structured through nested flashbacks from Rita’s perspective as she recovers from a sudden collapse. An intermittent voiceover gestures toward the novel’s interiority, but it is Wolf’s occasionally dreamlike montage and sweeping cinematography that carry the film. The film often resembles an East German Terrence Malick as it splits the difference between the proletariat (Rita’s apprenticeship at a railway car factory and her ideologically charged classroom studies) and the poetic (lyrical pacing and occasional spasms of ethereal imagery).

Images of duality recur throughout: trains moving in opposite directions, twin towers joined by a bridge, and spaces split by walls, windows, and barriers. At one point, the frame itself divides, juxtaposing the present with images from Rita’s unconscious. Wolf doesn’t pick sides. Neither the East, with its “meaningless difficulties,” nor the West. When the film finally crosses the border, the West appears simultaneously crowded and empty, noisy and muted—free, yet somehow constrained.

Divided Heaven screens tonight, February 1, and on February 8, at Anthology Film Archives.