A.S. Hamrah is most people's favorite film critic. Since 2008, he’s developed his signature form in n+1: pieces that collect short reviews of mostly current popular cinema into a loosely narrativized sequence that allows Hamrah to put the films’ various preoccupations in dialog with one another. His elastic tone can be acerbic, generous, and comically blunt. When he wants to, he’s very good at making the movies he writes about sound self-evidently stupid. Although he is one of criticism’s bona fide intellectuals and greatest insult comics, he writes without pretense nor condescension toward filmgoers. He sees many films as a paying member of the audience in general release, and context—including sometimes the reactions of his fellow viewers—often takes the foreground.

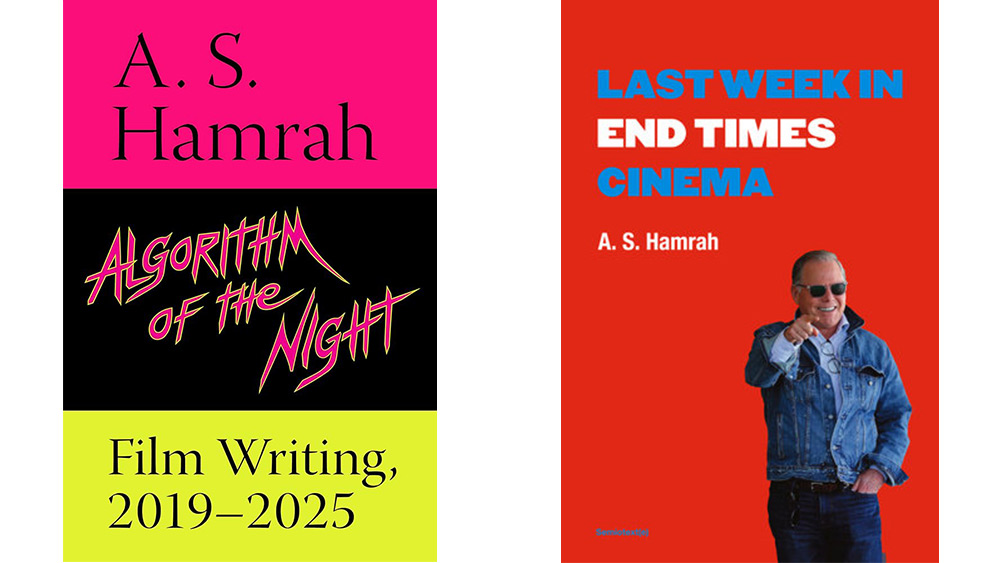

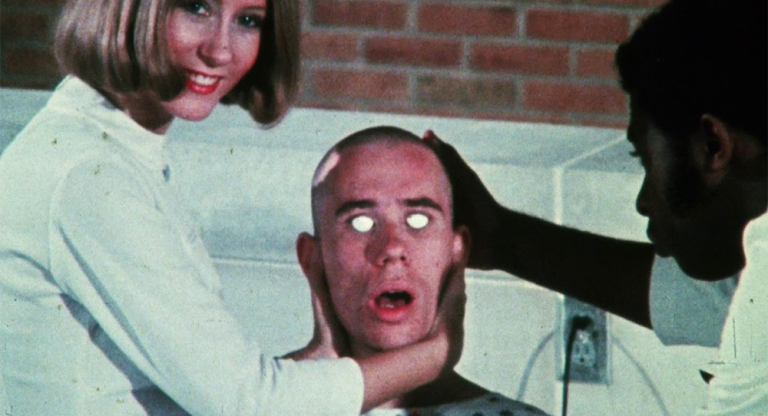

In the fall of 2025, readers were graced with two new collections of his work: Algorithm of the Night: Film Writing, 2019-2025 and Last Week in End Times Cinema. Algorithm is the follow-up to his earlier collection The Earth Dies Streaming: Film Writing, 2002-2018. Like its predecessor, Algorithm comprises most of Hamrah’s n+1 pieces alongside others authored for the Criterion Collection, The Baffler, The New York Review of Books, and other publications. (I commissioned and edited one of them, published in the book as “An All-Consuming Horror,” which considers consumerist horror films such as Chopping Mall and The Corpse Grinders.)

Last Week in End Times Cinema collects email dispatches Hamrah sent from March 2024 to 2025 digesting a year’s worth of dyspeptic entertainment news into droll one-line summaries. Separately, many of these news stories may have been read as isolated absurdities or faded from memory. Together, they form an important timecapsule of cross-referenced instances of greed, absurdity, stupidity, and genuine horrors during what is, if not the true end of, at least a crucial inflection point in the film industry. You can read it straight through, flip through pages and let your eyes skitter around the inanity, or almost read it like a book of aphorisms.

Hamrah has been on tour with the books for several weeks. On Saturday, January 31, he will appear at Metrograph to introduce Ace in the Hole and Land of the Dead. Hamrah is a longtime friend and an occasional interviewer for Screen Slate. As we were catching up, I mentioned I had just completed jury duty, and he asked me to start recording so he could share a story:

A.S. Hamrah: I was on a Grand Jury in Brooklyn around 2012. There are a large number of people on a grand jury, and they mostly just sit there and hear about whether cases should be brought to trial.

On the second day, one of my co-jurors came in with this large army duffel bag, and it was kind of ominous. When the lunch break arrived, he opened this big green army duffel bag and said to everybody in the jury pool, "Does anybody here like movies?"

And everybody said, "Yeah, I like movies."

And he said, "Do you like kids movies?"

And some people said, "Yeah, we have kids.”

And the duffel bag was filled with burned DVDs of popular kids movies. He said, "I'm selling these movies for $5 each." He did this openly and flagrantly in front of the entire staff of the court, with no compunction at all. Like, ten people bought movies from this guy.

Jon Dieringer: When my juror instruction video ended, the VLC player interface just hovered on screen, like we were watching torrented movies in the courthouse microcinema or something. But I appreciate bootleg DVDs as objects, and how they tell a story of a film’s life and circulation.

Something I respect about your criticism is how much you bring this total context: current political events, the circumstances of viewing at public screenings, the reality that the film industry has to a great extent become the tech industry now.

ASH: Since my two new books came out, people have pointed that out a lot. It became especially important during the pandemic, when critics were writing as if they were still watching films in theaters, but they weren’t. Everyone was watching links at home. There’s a big difference between seeing a film in a theater—Screen Slate knows that better than anyone—and watching it on a laptop or a Roku or whatever. The fact that critics were hiding how they were actually seeing movies didn’t seem legitimate to me.

JD: Even since before the lockdown, it has bothered me that most reviews are written as if the films are seen in some kind of state of objectivity. But context matters. The pandemic was a bit of a mask-off moment—no one could pretend they were viewing things in remotely normal conditions anymore.

ASH: As the critic for n+1, my deadlines are not like they are for people who write for daily newspapers or weekly magazines. And although I do go to press screenings, and I enjoy press screenings, I prefer to see movies with the paying audience after they come out, partially because I don't think it's imperative to review films the day they're released. I just think that's an industry standard that doesn't make a lot of sense anymore.

JD: The consumer guide, thumbs-up, thumbs-down model doesn’t really function the same way in the age of aggregators and social media.

ASH: The consumer guide aspect of criticism is something I've been fighting against since I started writing. In fact, last night at my event at Porter Square Books in Cambridge, there was an arts editor who I know from the time I lived in Boston. And he gave me a great compliment: he said, “You know, I read your work, and I can't tell whether you like these films or dislike them.” And he seemed kind of agitated by that a little bit.

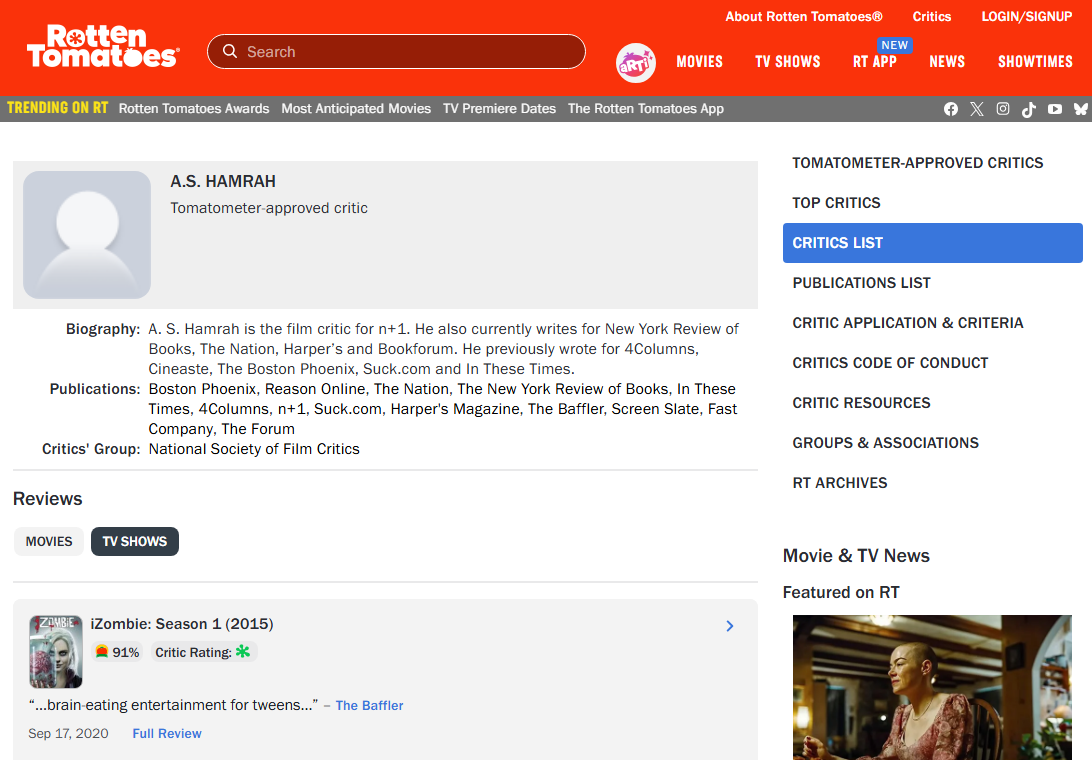

JD: You mentioned in the intro of Algorithm of the Night, something to the effect of how it’s very bleak when critics self-identify as “Tomatometer-approved,” really embracing that role as a consumer reporter and fodder for the algorithm.

ASH: Yes.

JD: Studios and marketing consultants have really mastered their ability to blur the line between fan and critic and engineered this situation in which many people who are able to pass as legitimate writers are grateful to mold themselves into pliant mouthpieces competing for retweets and pull quotes. It’s something I think many of these people do without self-awareness or overt instruction.

In the ‘90s, they had to invent these fake critics and it became a big thing. But now the algorithm is able to just cultivate this army for them. It’s something I find so extremely bleak about the state of modern film criticism. Even the fake criticism has gotten more depressing.

ASH: That fake critic was named David Manning, and he supposedly wrote for The Ridgefield Express, an actual small newspaper in Connecticut. It became a big scandal when it happened, because they completely invented a critic and got caught immediately. And it's true now, the fake critics are inventing themselves.

I call Rotten Tomatoes the Roll Call of Shame in the introduction. I don't understand people who are so happy that they become Tomatometer-approved, and why they seek validation from this absurd website that collates everyone's work, including mine, without paying anyone. They're making money doing that. They're not paying any critics, and it's owned by two film studios. [Ed. note: Rotten Tomatoes is part of Fandango Media, LLC, which is owned 25% by Warner Bros. Discovery and 75% by Versant, a company created in January 2026 as a spin-off of NBCUniversal’s cable and digital media holdings.] I mean, it's ridiculous that people find this to be a factor that they should have in their lives at all.

JD: At Screen Slate we’re considered “self-entry,” like we’re supposed to enter our own reviews. Which we haven’t done for several years. And every now and then I’ll get a message from a publicist or distributor or someone who works at Rotten Tomatoes asking us to add something to help juice the Tomato score or whatever. And I’m like, look, I get nothing from this. It’s another distraction from my day job when I should be stealing time to work on more important things. I can run my publication as an autonomous thing or I can just paste shit onto the Tomatometer all day. And even though we don’t monetize our traffic with ads or think too much about search engine optimization, we clearly see that it doesn’t boost those, anyway.

ASH: They did this to me too a couple of years ago. They said, “We want you to start self-reporting your reviews.” And I laughed. I said, “I don't work for you. I'm not your employee. Why would I do that? It’s not important to me whether you put my reviews on Rotten Tomatoes at all.”

JD: In the case of Screen Slate, which is very DIY, it’s like, I’m willing to work for free for myself, but I’m not willing to work for free for the Fandango corporation.

ASH: Exactly. The Fandango Machine.

JD: Big Fandango.

ASH: Big Fandango, yeah. The idea that they would actually ask me to work for them for free is insane. And anyone who puts Tomatometer-approved in their bio, you have to assume that’s what they’re doing, too.

JD: A lot of people seem very confused about how to become film critics. I think part of that is that it's apparently not an occupation anymore. But I also get pitches where I can tell maybe a journalism teacher or some mentor has advised them to write their pitches in this very formal way. And I don’t like to crush people’s dreams, but it’s very alienating to get these labored-over “in this essay I will”-type emails.

ASH: I mean, this something that I learned early in my writing life, which was in the 1990s, is that you just have to do everything yourself. Writing for zines and early websites like Suck.com, it was clear that there was no way the mainstream press was going to help anyone. They were already trying to pay you nothing and make you work all the time. It was a joke. You have to do it yourself. And I think the generation after mine expected a functioning world. In terms of film criticism, they expected a functioning world, and that was just going away.

JD: Some of these things like Substack are also a trap. They create a false sense of self-publishing and do-it-yourself, but you’re locked into these corporate systems that further atomize everyone. Rather than bring people’s voices together, it breaks them into little silos, and the more silos you have the more money Substack makes. But I also understand the appeal of it, because creating a platform from scratch sucks.

ASH: The reason Letterboxd works is because it gives people a sense of community around this. But really, if all those people who are in their groups of friends at Letterboxd just started a magazine, it would be better. They would have more legitimacy. It would be better for film culture than doing it on a social media site. Which is subject to enshitification, of course.

JD: What’s been happening with Mubi is a good example of a gap in perception between the sort of values a company has traditionally been perceived to have, and the reality of what their true interests and goals are. Which in their case are ultimately aggressive financial growth. The leaders within Mubi don't seem to understand why this community they created feels betrayed. It’s a good lesson for Letterboxd. Their users perceive them creating a social good and community hub. And the more capital you infuse into that type of operation, there's an intensifying pressure to generate profit that so often leads to decisions that leaves that community feeling betrayed.

ASH: There's a bigger problem too, which is that Mubi can have a great editorial team, which they do: Danny Kasman, is a brilliant guy, he knows what he's doing, and he's a good editor. But if the CEO of your company is talking to Variety calling himself the billion dollar company man, and you have an editorial division that's paying people low wages, that's going to seem very alienating to a lot of people. They're claiming they have billions of dollars to throw around, but then they're asking people to write for very little money. I mean, this makes this talented editorial staff look bad, right? And you would think that the CEO would have more awareness of that, right? But for some reason, he doesn't seem to care anything about even mentioning his editorial staff when he goes around bragging to Penske Media about how much his company is worth.

JD: I think there are probably a number of areas of the company in which he seems to lack self-awareness. But it's also part of this bigger trend, which is that so many film-centered publications still standing are kind of like loss leaders or marketing projects for companies. And that's not to cast aspersions on them or disparage the great work of people who edit and contribute to them. But it’s not a viable, long-term solution to creating a healthy and robust editorial culture around film.

ASH: Even if you're running your publication as a loss-leader or a marketing tool, you still have to respect the people that are writing for it. And you have to expect they'll understand the parameters of what they're doing. But you can't pay them wages that are befitting an independent publication, right? Which is what they try to do.

JD: I have yet to find a solution to paying myself or anyone else a sustainable wage through Screen Slate. And I think a lot of this spirals out into larger problems that create a vacuum of support for independent publications. And this leads me back to your criticism, because you’re able to effortlessly link public policy to what’s on screen. As one example of this, in your review of Harriet, you get into the discussion of British actors playing African-American roles. And you cite lack of support for arts in the US, lack of healthcare, the cost of living, the difficulty of developing young artists. And film producers basically turn to the UK and Australia.

ASH: Yeah, the Commonwealth countries make it easier for people to become actors. In this case, that leads to this idea that British people should be cast in all these American roles. There's this idea, in general in Hollywood now, that Americans can't play the underclass, so when there's poor and working-class people, especially if they're southerners, those parts are often played by British people. I don't think we need to see Robert Pattinson in a role like that. An American would understand better and probably do a better job.

My friend is an art department guy. He was working on a television series, and there was a guy playing a gas station attendant in a show that took place in the 1960s, and he's got one line. The guy did his line, and the director called cut. And then the actor says, “Okay, was, how was that?” in a British accent. You know, Guy has one line. He's playing a gas station attendant in New Jersey, and he's British, right? It doesn't make any sense.

JD: There is a lack of social programs and affordability that enabled so many people in the mid-20th century to become great actors. You read someone’s Wikipedia page and it’s like, they joined the U.S. Merchant Marine, worked as a truck driver and a stevedore, studied acting on the GI Bill, and paid $5 rent while acting in off-Broadway plays.

ASH: Or they’re like Robert Mitchum. He dropped out of high school, he was a hobo, he was riding the rails, he stumbled into acting and became the greatest actor of all time. That doesn’t happen anymore, because the American film industry is reliant on RADA to provide it with actors. They’re not looking for people like that.

JD: American society has become hostile to the possibility of hobo actors.

ASH: I think there’s also the sense that people like that are less controllable.

JD: These books came out around the same time. Algorithm picks up where The Earth Dies Streaming left off, but it’s also right at the cusp of COVID. And along with Last Week in End Times Cinema you’re capping off this period with a moment of corporate consolidation and disarray. Why publish both of these books now, covering this time period?

ASH: At the same time as I was putting together Algorithm of the Night, I started doing the Last Week in End Times Cinema newsletter. As the film industry was becoming more degraded, and the situation was getting more dire, one day, I just made a little Instagram story post, which was the top four idiotic film industry news stories of the week. My friends said, you should do this next week. So I did it next week. I did it that way for about four weeks, but I realized after that that I wanted to put more things than would fit into that space. Someone suggested it should be a newsletter, and then I started just emailing it to people that asked to get it. Over the course of the year, I ended up with about 1,000 subscribers. All for free by email, it wasn't a Substack or anything like that. I could have continued, but I got tired of doing it. And I especially got tired of doing it after the period of the LA wild fires and when David Lynch died.

JD: I don’t want to put too much emphasis on guys named David, but I think losing Bowie and Lynch kind of bookended this period from 2016-2025 of the rails falling completely off of western civilization, like they were the cosmic glue holding everything together.

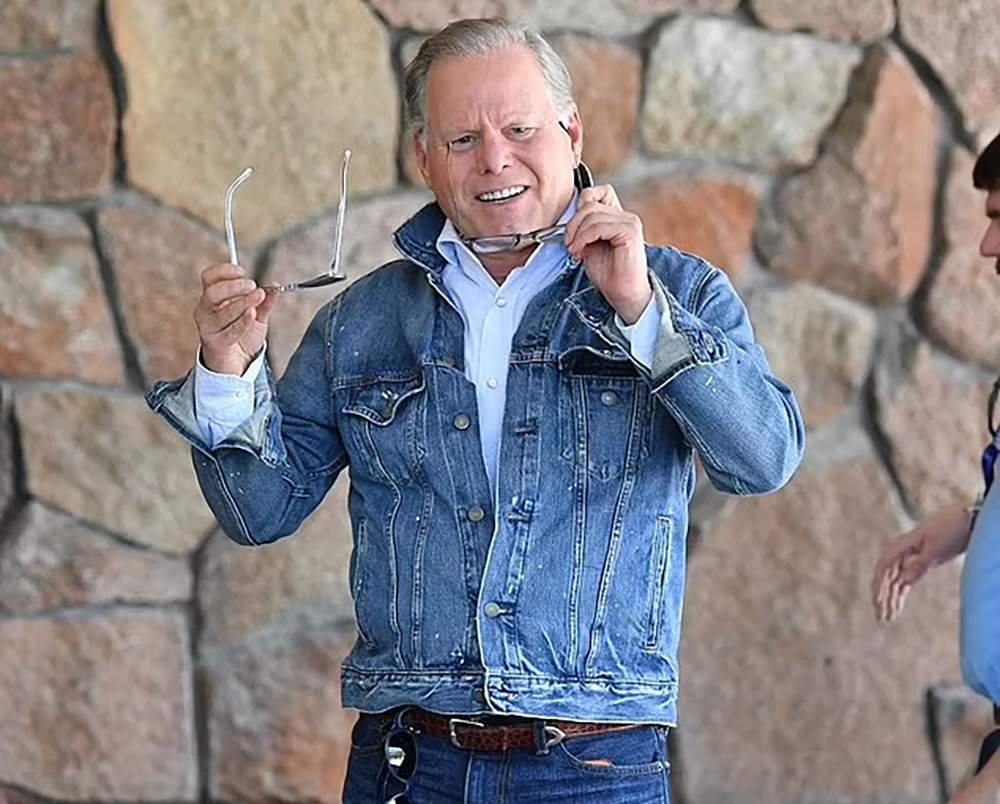

ASH: And then you have David Zaslav on the cover of Last Week in End Times Cinema. The Final David.

JD: I sort of worry, what if he’s the false final boss. What if he’s destroyed and we find out he was actually a bulwark against an even greater evil.

ASH: He's the handmaiden of that, right? That's what he wants to happen. All he cares about are mergers and acquisitions and becoming a billionaire himself. He doesn't care about the health of the film industry, or even if good films are made. I mean, he does want to win Oscars, which drives up the value of his company. But that's all he cares about.

This is kind of a side note, but a number of people don't recognize him on the cover of the book. So some people have said to me, that's a good picture of you on the cover of your—

JD: Oh, no.

ASH: I'm like, what? People who know me…

JD: He looks like Skeletor or something. He’s got the skeleton demon phenotype.

ASH: He has three sets of eyeglasses on his person in that photo. He’s wearing sunglasses. He's got a pair of glasses in his pocket, and he's got a pair of glasses hanging out of his jeans pants pocket.

Some other people said to me, “Why did you put Joe Biden on the cover of your book?” As if I would do that under any circumstances, you know?

JD: Something else I've noticed about film news and criticism lately is that I find it, from a practical point of view, increasingly difficult to read. Often literally impossible in the sense of: my browser gets bricked, I’m asked to turn off ad blocker, but the ads crash my new computer, or you can’t see anything without clicking an X on the ad but the X opens another pop-up and some weird program starts downloading. How did you manage to read these websites?

ASH: This is a very, very good question, because while I was doing Last Week in End Time Cinema as a newsletter, the most frustrating part about it was, when I read the news every morning, either on my laptop or my phone, the amount of times I had to hit the X to get ads out of my face so I could actually read the news. And part of, part of the reason I only wanted to do it for a year was because I got sick of doing that.

JD: The articles also have a lot of padding. A news article that could be one sentence has hundreds of words of extra text that seems to be either boilerplate or AI-generated, presumably because Google ranks longer articles more highly.

ASH: It's become de rigueur in these kinds of pseudo-journalistic pieces where they have to recap so many aspects of the person's career or the production history of the film that they're writing about. It's just completely unreadable waste, garbage that's clogging up the internet, like so much of everything else there now. And obviously, let's just reaffirm that Penske is a monopoly that should not exist. Penske media should be broken up. It's absurd that they're allowed to own every entertainment publication out there. [Ed. note: Penske Media owns Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, IndieWire, Deadline, VOXMEDIA (including New York, Culture, etc.), Artforum, Art in America, Rolling Stone, and many others.]

JD: Regarding the title of your book: where you fall on the spectrum of doom? Do you think this is the end? Or is it mostly tongue-in-cheek?

ASH: Of course I don’t know what’s going to happen. But it was tongue-in-cheek. In one of the books I quote Godard: “I await the end of cinema with optimism.” I think that this is a period that needs to be gotten through.

JD: I find it to be a moment of great opportunity, in a way. I don't mean for people who are trying to create value for shareholders. I mean that these periods of upheaval often lead to incredible things. The rise in interest in repertory cinema is promising. Corporations are making so much garbage and trying so hard to ram it down people's throats, and as audiences flee from that they discover massive troves of cinema history in areas that are far more enriching and exciting. Young people are driving that. Even if you look at the mainstream end, like the box office of Marty Supreme is mostly younger viewers.

ASH: This is something that we were discussing last night during my bookstore event at Porter Square Books: how younger cinephiles are taking the reins despite all this other stuff. And I think it's important they start magazines and investigate various forms of cinema that have been ignored.

In the late ‘60s Manny Farber described this great influx of all different kinds of cinema as “a loosening of the bowels.” I think this moment is similar to that in some ways. I'm introducing the film Nouvelle Vague tonight at The Brattle in Cambridge. It's interesting that that film appears now, because it's about a group of young people changing the future of cinema. It’s about film criticism, because a lot of the dialog in it is taken straight from the reviews and essays that Godard wrote at that time before he was making Breathless and that Truffaut also wrote around that time. So it's an example of putting film criticism into action. And I think the fact that it's a period piece is beside the point in a way.

JD: Even though it's distributed by Netflix?

ASH: They should know that the call is coming from inside the house.