Titles matter, and sadly, they were not the strong suit of French director Yannick Bellon, whose films are being showcased at L’Alliance New York this month and later this Fall. Cinephiles may be aware of Bellon’s work through her collaboration with Chris Marker, Remembrance of Things to Come (2001)—title undoubtedly Marker’s—which was one of the first films screened in this series. It is a portrait of Bellon’s mother, the still photographer Denise Bellon, who had the rare gift of folding past and future into each of her images of a definitive present. Like Marker’s La Jetée (1962), Remembrance of Things to Come is composed of still images combined with a continuous voice-over, through which we can fathom the associative movement of Marker’s mind. Perhaps L’Alliance New York could reprise it in September, in the second half of the Bellon series, which includes another of her short documentaries, Colette (1951), in which the writer speaks for herself.

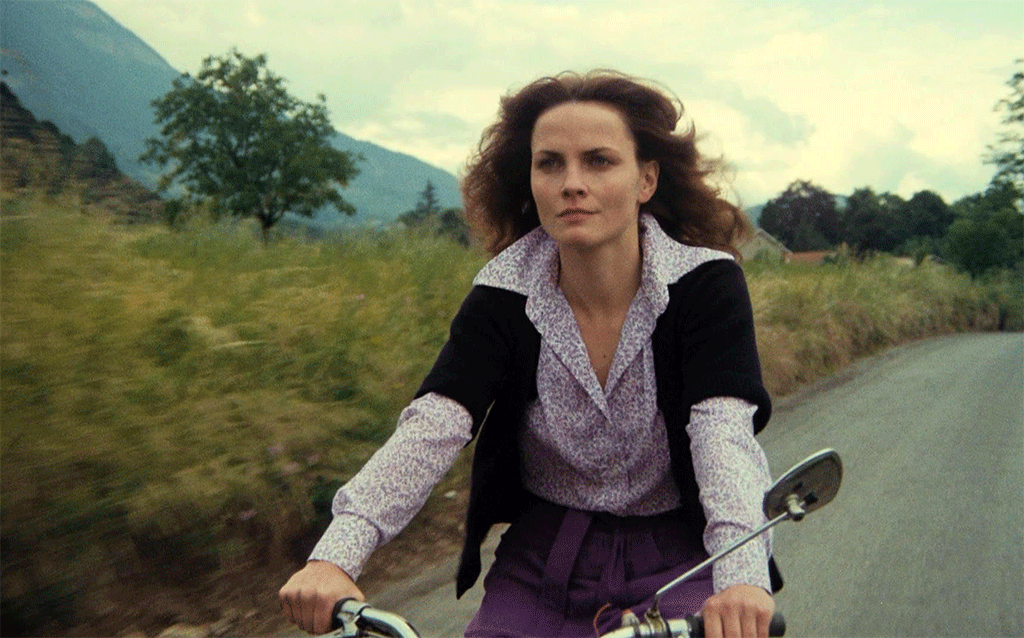

Bellon had a long and prolific career, beginning with short television documentaries and by the 1970s moving into features, eight of which were fiction. Like almost all of these, 1978’s Rape of Love (L’amour violé) is a social issue movie with a woman at the center. Nicole (Nathalie Nell) is a visiting nurse, respected by her colleagues and patients. She lives in Grenoble, a small city in southwestern France at the foot of the Alps, surrounded by farmland. While her fiancée is finishing his military service, she shares a house with her mother, a dressmaker. Independent and self-confident, Nicole rides a moped everywhere. One evening, she is forced off the road by four guys in a van. They kidnap her, drive her to a deserted woodland, and gang rape her. Bellon shows the abuse in detail: the slaps, punches, stripping of clothes. The actual acts of penetration by the four men are shown more quickly, but there is doubt about their brutality and the power the men feel while inflicting pain and humiliation. Nicole somehow makes her way to a clinic where she works. Her closest friend, and one of the doctors, attend to her and make a record of her injuries. Nicole is traumatized, but when she tells her mother and her fiancé what has happened, and that she wants to go to the police, they turn on her, implying that they will be the victims of her disclosure. It is not until she sees one of her rapists, working at a local store, that she realizes that only by reporting him and his colleagues, as it were, will they be prevented from repeating their crimes.

Rape of Love is a film about agency: Nicole is a young woman who believes she is in charge of her life. Her rapists attempt to destroy her self-determination, and in slightly different ways, so do people who profess to love and value her. She does not go to the cops for revenge—indeed nothing could be further from the current crop of revenge thrillers than this film. Nicole demands justice and, in that pursuit, she regains her freedom and sense of self. Bellon’s screenplay and direction has notable clarity and intelligence. She is also a superb director of actors. If the film has a flaw, it is that the narrative often feels like a series of bullet points rather than sourced from conflicts that today are no more resolved than they were nearly 50 years ago. And if anyone can parse the meaning of the title, please let me know.

If Rape of Love suffers from an excess of control, Bellon may have been addressing her own filmmaking fallibility in two films she made a decade later: the documentary Escape and the related narrative Children of Chaos, both from 1989. Both are based in the work of the Théâtre du Fil, an arts project where adolescents and young adults, released from prison on probation, trained in all aspects of theater with a troupe dedicated to their rehabilitation. In Children of Chaos, Marie (Emmanuelle Béart), a teenage heroin addict, is invited to join a theater troupe which performed at the prison where she was held. The invitation is a no brainer, considering that Béart is one of the greatest beauties in the history of world cinema. (Jacques Rivette made a four-hour film¸ 1991’s La Belle Noiseuse, dedicated to the observation and representation of Béart’s remarkable ass.) Marie, however, is not only a beauty. She has an emotional intensity and a desire to perform on stage that at times eclipses her desire for heroin, and at other times does not. Unlike Agnès Varda’s Vagabond (1985), which would make an interesting double-bill with Children of Chaos, Bellon’s narrative has no definitive conclusion, and is all the more powerful for that.

Rape of Love screens this evening, July 15, at L’Alliance New York as part of the series “Yannick Bellon: The Happy Pessimist.”