The United States reached its peak beef consumption in 1976, reaching just shy of 95 lbs per capita. Perhaps not coincidentally, 1976 was also the bicentennial, a nationwide birthday party that permeated domestic mass culture. This was the milieu in which Frederick Wiseman spent the capital earned by Welfare, whose anointing as a "masterpiece" by establishment critics helped him land a second five-film "do whatever you want" contract from the public television station WNET, by releasing his tenth documentary in as many years about the Monfort meat-packing plant in Greeley, Colorado. Characteristically, the film was titled Meat.

Unfortunately, Meat did not enjoy the same plaudits and was generally panned by the critics who bothered to review it. Though the film has an austerity in speech relative to its loquacious predecessor, due largely to the fact that cows and sheep can't talk (or beg for their lives), the films share vital connective tissue. Along with 1974's Primate, Meat and Welfare form a critical trilogy we might title "Processing" that shows the totalizing effects institutions have on re-shaping individuals and their lives, or indeed, as is the case with Meat, the end of them. How can one enter the world as an egg and exit it as a centrifugally separated tube? Meat holds the answer.

But this isn't just the case for those subjected to the whims of a given institution, but also for those tasked with carrying out their operations. For Meat, perhaps better than any other example cleaved from his essential corpus, shows the efficacy of Wiseman's signature brand of decontextualization—a technique that depicts the true nature of a given activity divorced from its functional justifications. As much horror as viewers unaccustomed to "how the sausage is made" might experience at the twitching bovine sinews revealed by decapitation and skinning, there is perhaps just as much to be found in the non-plussed stance of calloused professionals whose blades undertook that labor while they kept abreast of the Broncos' game on a portable TV.

While an extreme example, this sort of institutional inurement stretches both forward and backwards for Wiseman, elucidating not just the treatment by the infamous doctors and guards at Bridgewater in 1967's Titicut Follies, but also how a well-intentioned official in 2020's City Hall could posit—with a straight face—that Boston's highest-in-the-nation income disparity between white and Black residents could be addressed with the advent of a high-school-to-Amazon-warehouse worker pipeline. Now, when this country ostensibly plans to somehow celebrate yet another 50 years of an experiment Wiseman has repeatedly revealed to be sorely lacking at best and deliberately destructive at worst, I couldn't help but think of Meat when confronted by ICE's recent conduct in Minneapolis. In a 2018 interview with Richard Brody in The New Yorker, the filmmaker claimed that "the general public is living in Bridgewater now." In 2026, we may have found ourselves all living in Monfort.

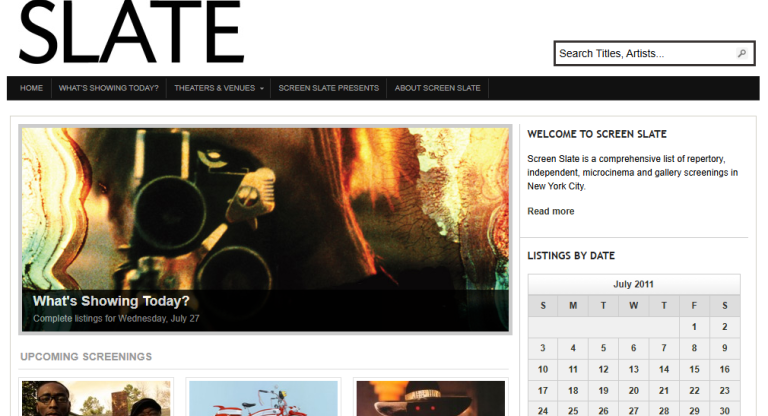

Meat screens this Thursday, February 19, at BAMPFA, the final film in the series, "Frederick Wiseman: America at Work," and continuing the series, "Climate Journalism on Screen."