The question of Andy Warhol’s authorship in relation to his post-Empire films remains a perennial point of debate, often centered around how much he actually contributed to any given production, particularly in terms of what even qualifies as “directing.” Things get even murkier once Paul Morrissey enters the picture, as one could take his version of events at face-value since Warhol is no longer with us to defend his own legacy. Morrissey claimed that he did everything while Warhol was either too incompetent, too “autistic” (his word, not mine) or, at least in the case of L’Amour (1973), too distracted to meaningfully contribute. (To be fair, during much of the shoot, he was reportedly antique shopping with Yves Saint Laurent.)

Now, does that dirty word, “director,” amount to engineering improvisational bohemianism? If so, then sure, Warhol was a “director.” But, it might be more accurate to file Warhol under the nebulous header of “artist” and Morrissey under “filmmaker.” That’s not to imply Morrissey wasn’t an artist himself, but to emphasize that the more traditional functions of a director—blocking, timing, narrative-shaping—are far more legibly his in their collaborations.

In L’Amour, Morrissey’s idiosyncrasies are unmistakable. As a moralist preoccupied with the failures of permissiveness, and as a traditionalist embedded in the ‘60s downtown avant-garde arts scene, his direction clings to classical form, even as his characters rant, flail, and seduce their way through scenes that feel barely contained by their unpredictability and aversion to conventional pacing. L’Amour’s content may be ramshackle, but its worldview—conservative, ironic, almost puritanical—holds firm. The film’s narrative is as conventionally linear as it gets: two American high school dropouts flee the United States, head to France, and find love in Paris. “Two Americans in Paris,” it could have been called; it even carried the working title “Gold Diggers '71.”

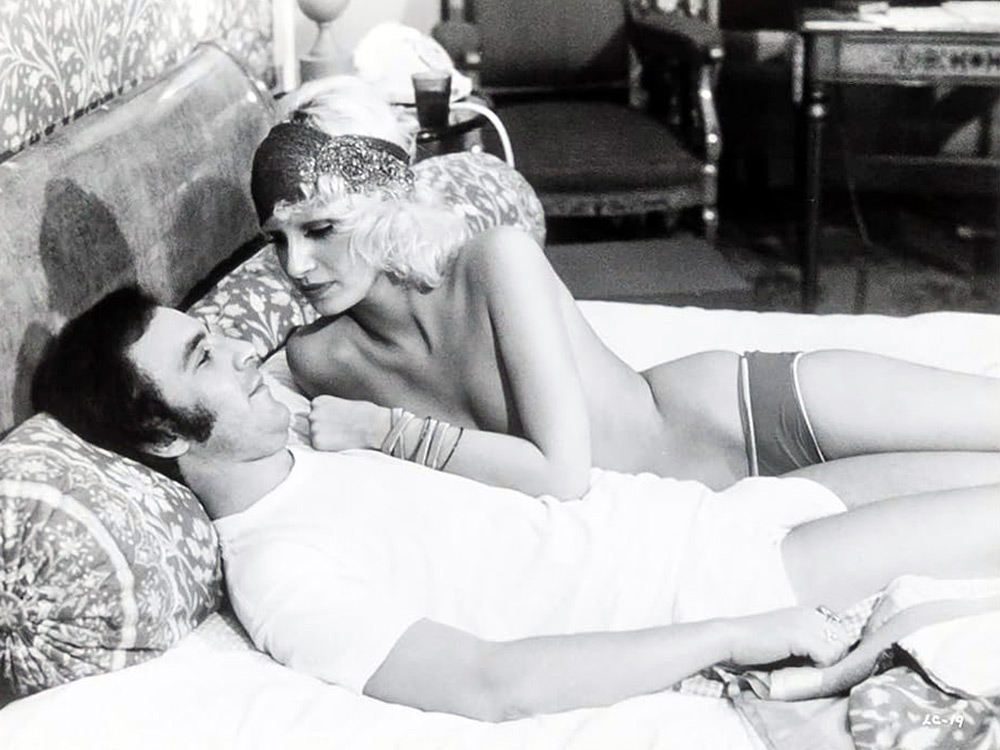

The two women in question, Donna and Jane (played by C-tier Warhol Superstars Donna Jordan and Jane Forth), meet up with Michael and Max (Michael Sklar and Max Delys). Together, they skate around Paris and engage in several indoor shouting matches. (As Stanley Eichelbaum noted in his contemporaneous review, the city itself is barely acknowledged; Morrissey could’ve just as easily shot the film in the East Village, given how much of it takes place inside.) And while hammy scenery-chewing is a feature, not a bug, of Morrissey’s work—meant, on some level, to provoke laughter through sheer ridiculousness—the histrionics here are cranked up to eleven. When the actors don’t know how to end a scene, they either shout their lines, flail around aimlessly, or, in Sklar’s case, perform some high-strung combination of both.

It’s possible that Morrissey’s contempt for this unruly group of expatriates is simply through the roof. The closeted Michael, the wealthiest of the bunch, is the heir to a urinal block tycoon; his family’s fortune, quite literally, built on shit and piss. Or maybe the film is just straining to make its lowbrow interests seem exciting, even vaguely edgy? This was the first R-rating that Warhol or Morrissey received after all. But quite frankly, much of it registers as a tad boring—not typical Warhol boredom, mind you, but boredom of an unproductive sort. Donna eventually agrees to consummate her marriage to Michael, but only on the condition that he gets her on the cover of Vogue magazine. Max, who needs no particular motivation beyond libido, sets his sights on Jane. They fuck, they fight. Max eventually goes his own way for vaguely explained reasons, and Donna eventually gets the glamor shot she’s been chasing for 80 minutes. Whatever critique L’Amour might be staging—of bourgeois fantasy, romantic delusion, or the empty promises of beauty—ends up lost in the noise. No pearls, just grit—which, now that I think about it, might be the perfect slogan for Morrissey’s collaborations with Warhol.

L’Amour screens this evening, June 5, at Anthology Film Archives on 35mm. Anthology’s description notes, “the 35mm print - the only one that is currently available - is significantly faded and worn; be prepared for a bona fide grindhouse-style screening!”