Our dispatch of the 2026 International Film Festival Rotterdam comes courtesy of Cici Peng and Beatrice Loayza, who assessed the festival’s sprawling slate of new releases and restorations.

Cici Peng

As is always the case with the International Film Festival Rotterdam, each attendee’s path largely diverges from their peers given the magnitude of the festival. This year’s edition comprised 428 features and shorts. As such, broaching the World Premiere films can oftentimes feel like tiptoeing across a field of landmines—at least, until word-of-mouth reviews begin to circulate among peers. This year, the best works appeared to be debuts, which is perhaps the most exciting constant of a festival that has long positioned itself as an incubator for new voices. While one might reasonably assume that these films would be found in the prestigious Tiger Competition, which prides itself on celebrating “the innovative and adventurous spirit of up-and-coming filmmakers,” the majority of the Competition films went down like medicine, with didactic plots workshopped to a smooth pulp. By contrast, the films featured in Bright Future, a sidebar with 18 feature debuts, were more unwieldy and likely to sidestep such formulaic genre regurgitations. This reality begs the question of who the Tiger Competition is for and why the festival continues to organize itself around categorizations that so often obscure, rather than illuminate, its most vital films.

One of the true discoveries from Bright Future was the New York-based filmmakers Kevin Walker and Jack Auen’s Chronovisor, a conspiratorial tale of obsession that follows a neuroscientist, Beatrice Courte (Anne-Laure Sellier, a real academic at the HEC in Paris), as she researches the titular device, a time-travelling machine invented in the 1960s by the Italian Benedictine monk and musicologist Pellegrino Ernetti (a real event, as detailed in a select few articles and reddit threads). The film knowingly feeds into our present appetite for conspiracy and investigates the strange paradox by which even the most pious seek out empirical proof.

Despite the machine’s gift of image-making, the film leans intrepidly into the drama of the written archive. After all, In the beginning there was the Word. I know, it might not sound particularly thrilling to read a film, but Chronovisor treats logocentric interpretation as a form of investigation, à la Umberto Eco, who is referenced in the film’s credits. The mise-en-scène’s textual terrains—with their varying typographies, textures, and marginalia—invite viewers to scour through an untrodden terra aperta aided by the pomp of Gustav Holst’s soundtrack. Shot on warm 16mm by Leo Zhang, Chronovisor takes place almost entirely within the dark cachés of New York libraries. Reverse-shots of Courte’s nerve-stricken blue eyes against close-ups of the text sources she amasses—a litany of English, French, German, and Greek periodicals—generate an exquisite form of tension, drawing the viewers—bated breath—into complicity within the centripetal force of her hypotheses. The filmmakers foreground selected segments by literally glossing over the original text with glowing English translations (rather than subtitles) that tease out questions about translation, interpretation, and how individual biases can narrow research. This is all heightened by slow zooms onto single phrases and a repeated montage that recalls Michael Snow’s So Is This (1982). What makes Chronovisor so brilliant is the instability of its epistemology, which thrusts us into the same nagging skepticism that haunts Courte. When do we pass from the realm of non-fiction to that of fiction? Which texts are fabricated, if any? How much of the film is simply our re-tracing of the directors’ own obsessive trail?

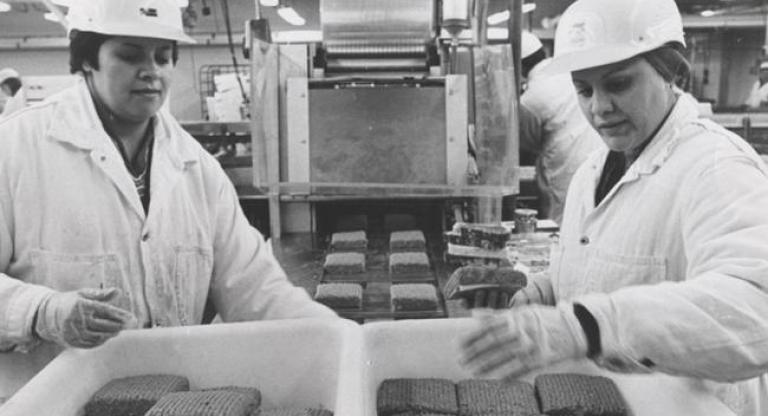

Another film that deliberately plays with textual reinterpretation and the codifications of genre is James N. Kienitz Wilkins’s The Misconceived (pictured at top). On one level, the film operates as a labor satire, staging the class tensions between a trio of construction workers—the older, traditional blue-collar Widgey; Tyler, a single-dad who has given up on filmmaking to raise his child; Mickey, a Gen-Z trollish stoner who peppers comic relief throughout the film with edgy race jokes—and their sculptor boss, Tobin, who salivates at the prospect of inclusion in the Whitney Biennial. As it turns out, Tyler and Tobin were formerly friends at art school and the film peels back the tensions that ripple outwards from this shared history, culminating in an explosive debate between Tyler and Tobin at the latter’s studio-visit-cum-party, which is being staged to pander to a goth 21-year-old curator.

On another level, the film is an enthralling, acerbic metacritique of the indie filmmaking conventions that builds upon the concerns laid out in Wilkins’s previous feature The Plagiarists (2019). Here, Wilkins’s medium is the message. Built in the Unreal Engine (an open-source videogame software), with characters rendered through motion-capture technology, and a soundtrack of Pond5 royalty-free stock music, Wilkins’s no-budget materialist satire repeatedly employs the codified formal tics of the “indie film”—close-up shots, fast cuts, verbose bickering, a climactic party sequence—alongside the outright diegetic markers of the creative class—Whitney Biennial catalogues casually strewn across a floor and Artforum being referred to in conversation as a porn magazine—to hammer home the economic straits and industry string-pulleys that systematize and confine filmmaking at a structural and individual level. During the climactic debate sequence, Tobin and Tyler’s argument is stitched together with wholesale lifts from Richard Brody’s “Best Films of 2023” write-up and Violet Lucca’s critique of Wilkins’s own work, as if offering a final derision of the recursive feedback loop that plagues the creative industry. Originality is pulverized by consumer-first production chains, dinner-party debates are just animated regurgitations of web essays, and authenticity is now but a pre-internet mirage. Wilkins’s self-interrogatory pessimism makes Schopenhauer seem sunny. At points, however, his intensely insular form of critique begins to gorge on itself to the point at which any possibility of open interpretation is hijacked by its self-conscious referentialism.

There were three African films in the Tiger Competition out of a total 12 African premieres (shorts and features combined) at the festival, alongside a focus on the Egyptian filmmaker Marwan Hamed and the Belgian-Congolese Collectif Faire-Part. And, while the continent represented only a measly proportion of the entire program, the festival nonetheless positioned this edition as paying heightened attention to African cinema in comparison with other European festivals. Although the South African drama Variations on a Theme won the Tiger Award, it was another South African debut, Nolitha Refilwe Mkulisi’s Let Them Be Seen, from the Bright Future section, that struck me as particularly remarkable. Unlike the former, it eschews an expository narrative for an altogether more outré non-fiction portrait of Tapoleng, a village in the Xhosa-speaking Eastern Cape (a region known for its concentration of churches and history of missionary neocolonial influence).

Bringing together tongue-in-cheek improv performances, a covert love affair, sublime landscape imagery, and absurdist elements, Let Them Be Seen subverts one’s expectations of what a so-called “rural” film can be. No effort is spent on attempting to expose the religious conservatism of individual subjects. Instead, Mkulisi, taking a similar approach to the photographer Santu Mofokeng in his Chasing Shadows series, teases out the ways in which the South African landscape has consistently been mythologized in the biblical vernaculars of the Dutch and English colonizers, who cast it as a kind of “promised land.” Mkulisi further complicates the stillness of such imagery with the presence of a prismatic community: their leisure, movements, and voices. What makes the work so striking is its simultaneous expansiveness and incompleteness. Mkulisi employs multiple formats, including both color and black-and-white DV-footage, iPhone recordings, and DSLR captures. Her subjects are largely untrammeled by authorial direction, either taking the camera into their own hands or veering into performative territory as they emulate their favourite 1990s TV show Jam Alley. The observational landscape sequences are frequently upended by gaggles of women wearing primary-colored wigs who dance, strut, and sing boisterously to a bovine audience beneath the looming mountains. Playfully undermining the non-interventionist poetics of the landscape film, Mkulesi injects the rural with a spritely dose of pop-inflected sensuality.

Youthful drifters populated two coming-of-age debuts I watched toward the end of the festival. Charlotte Zhang’s Tycoon is a lo-fi dystopian work set in the near-future Los Angeles of 2028, as the city is on the cusp of the Olympics amid a viral livestock outbreak. Despite its quirky premise, the film ostensibly follows a pair of working-class grifters (Miguel Padilla-Juarez and Jon Lawrence Reyes) who hustle for a quick buck within an atmosphere scaffolded by a GTA-inflected soundtrack, an early Harmony Korine-esque flattened DV-aesthetic, and extratextual winks to Michael Mann’s alternate vision of LA in Heat. The result is a solid but torpid portrait whose familiar textures felt slightly too neat.

The German filmmaker Stefan Koutzev’s less-seen Why hasn’t everything disappeared yet accomplished more when it came to its depiction of young adult ennui. In it, a young Korean drop-out, Sori Moon (Juho Lee), leaves his home country for Cologne in a decision that we come to learn is driven by his post-military service trauma. Although the premise sounds fairly rote, Koutzev and Lee’s co-written script percolates with a sense of alienating intimacy. As Moon drifts between odd jobs that lead to fleeting encounters with strangers, their conversations often dissolve into Moon’s confessional monologues about the casual cruelty of his former military comrades—a pain that bubbles up incessantly. In one sequence, he soliloquizes to a German woman in Korean; she can only stare blankly as Moon mumbles while sketching in his notebook, his face cherubic and inscrutable.

Koutzev’s long takes anchor Moon within his new, lonesome environment, stripping the narrative of propulsive force and instead allowing an air of despondency to seep into the slackened temporal fabric of his world. The film’s final shots settle on an airport which, while a predictable metaphor, are delivered from cliché thanks to Koutzev’s decision to linger on the smoke plumes that trail behind jet engines: the only vestige of a fire that burns thousands of miles away.

Even as many of the debuts at IFFR flirted with well-trodden narratives and genres, the filmmakers proved their mettle through new methodologies: Koutzev extends familiar diasporic metaphors with surprisingly affective details; Mkulisi buoyantly bricolages the landscape film; and, perhaps most audaciously, Jack Auen and Kevin Walker imagine a detective film for readers. In a film ecosystem shaped by constrictive funding structures and increasingly risk-averse, trend-driven storytelling, originality can often feel scarce, yet here, the images insist on being seen anew. —Cici Peng

Beatrice Loayza

Rotterdam is a festival of curiosities, pridefully so, meaning you’re more likely to learn something out of the ordinary about the history of cinema and alternative modes of global production than necessarily stumble upon a neglected masterpiece—no matter the frequently hyperbolic program notes, which, I get it, are part of the gig. That’s not a diss but a reframing of expectations, and I think a better way into the Dutch festival’s eccentric retrospective programming. Case in point, this year’s deep focus program on Japanese direct-to-video films of the ‘80s and ‘90s, bite-sized genre works that span early J-horror, yakuza joints, and softcore comedies. These cheaply-made movies lack the aesthetic polish of their theatrically-released counterparts, but they make up for it (sometimes) with unhinged storytelling and a rousing indifference to good taste. On this latter point, Shun Nakahara’s Anxious Virgin: One More Time, I Love You (1990) excels, which might be obvious from the title. A bizarro mix of magical rom-com and teen pinku with laughably chintzy effects (oh, to watch this in a room of mostly elderly Dutch folks…) Anxious Virgin imagines an afterlife scenario in which a sex-obsessed teen boy is mercifully sent back to Earth to lose his virginity but with a twist: he’s reanimated in the body of a schoolgirl. This puts him in the awkward situation of lusting after the schoolgirl’s best friend, though that (technically lesbian and thus impossible) desire eventually takes the shape of jealousy and brotherly protectiveness when the gal pal pursues a known Lothario. In a sense, it’s a classic tale of moral redemption—not all men!—but the detours from the principal plot build out a frankly vile portrait of masculinity that feels especially jarring because of the film’s intended levity. In one digression, for instance, three horny adolescent stooges watch two schoolmates get to third base in a secluded park; when the girl is blindfolded by her partner, the trio steps in, ties up the loverboy, and starts fondling the unsuspecting gal. Naturally, this rape scene is played for gags.

The direct-to-video system also employed a handful of now-esteemed directors before their artistic breakthroughs, like Takashi Miike (Fudoh: The New Generation, 1996) and Shinji Aoyama (A Weapon in My Heart, 1996). Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Shoot Yourself or Suit Yourself!! (1995) was the last DTV film Kurosawa made before Cure (1997). Some formal choices—slow pivot pans and fastidiously composed single-takes—evince the filmmaker he has become. Otherwise the film stands independent of Kurosawa’s auteur-oeuvre, which is not to say it doesn’t deliver on other fronts with some surprisingly insightful social commentary and satisfying gags. A kind of post-yakuza yakuza film that anticipates the Japanese government’s later crackdowns on organized crime, Shoot Yourself follows two layabouts who become embroiled in a future politician’s crusade against the group. The do-gooder’s target, however, is just a humble tatami weaver who doesn’t deny the accusation—that he’s mistaken for a yakuza is awfully flattering. The film’s postmodern games poke fun at the crime genre, whose grip on the cultural imaginary might also be responsible for the kind of baseless fearmongering displayed in the film. In any case, Kurosawa gives us a smoky shoot-out by film’s end, lest one be denied the genre’s attendant spectacle.

Elsewhere, in the festival’s Cinema Regained program—a catch-all of recent restorations and premieres of new work cut from old ones (like Norbert Pfaffenbichler’s ADGIN PRRX, a 3-hour re-edit of John Frankenheimer’s 1966 film Gran Prix)—I was particularly taken by a program of Czechoslovak shorts from the 1930s, many of which deserve a more prominent place in the canon of early avant-garde film. Over a decade before co-directing Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) with his collaborator and (for a few years at least) wife Maya Deren, Alexander Hacenschmied (who adopted the name Alexander Hammid upon immigrating to the US in the late ‘30s) was pivotal in bringing international attention to Czechoslovak film-art. In his Aimless Walk (1930), city symphony meets surrealism when a listless urban man encounters his doppelganger on the outskirts of Prague. And, in Hands on Tuesday (Čeněk Zahradníček and Vladimír Šmejkal, 1935), an assembly of hands, in close-up and/or seemingly disembodied, are captured like slapstick stars, or at times arranged like Busby-Berkeley dance numbers. My favorite of the bunch, however, was Atom of Eternity (1934), also by Zahradníček and Šmejkal. A cheeky boy-meets-girl romance turned Ophelian tragedy, the short’s frank symbolism consistently fills in the gaps in amusingly inventive ways. Hitchcock must have seen it before North by Northwest (1959) as that film’s famous climax directly rips off Atom’s shorthand for sex: of a train going in and out of a tunnel.

Sex is also displaced and re-coded in Muriel Box’s The Passionate Stranger (1957), though it relies on a particularly clever use of Technicolor to achieve this separation. Box was essentially Britain’s Ida Lupina, a prolific female filmmaker at a time when this was still unusual (though Wendy Toye wasn’t far behind), and her particular touch tweaked genre codes with uniquely feminist tailoring well ahead of its time. The Passionate Stranger is ostensibly working in the register of a Sirkian melodrama when it opens with the arrival of hunky Italian Carlo (Carlo Justini), a wealthy British couple’s new driver. Carlo’s employer, Roger (Ralph Richardson), is physically impaired, which might make Carlo seem all that much more attractive to Roger’s novelist wife Judith (Margaret Leighton). Instead, Judith sees in the exotic stud fuel for her latest bodice-ripper, a draft of which Carlo gets his hands on and reads in its entirety over the course of one afternoon. As Carlo becomes immersed in this fantasy world of Judith’s novel, the film switches from black-and-white to vibrant color, where it spends about half of its runtime chronicling the love affair between a lady and her driver (played by slightly altered versions of Judtih and Carlo). Carlo is emboldened by this drama to pursue Judith in real life. Against expectations, Judith is blithely uninterested. Hypothetical reveries are one thing—having a sputtering himbo around while you’re trying to meet a deadline is another. —Beatrice Loayza