Like most, it was a viewing of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960) in my teenage years that made me fall in love with cinema, or at least a kind of cinema that I’d continue burrowing myself in for years to come. But it wasn’t until later, in college really, that I started to look beyond the French New Wave to understand French cinema. And so, while Godard remained top of mind when it came to thinking about film, suddenly figures like Teo Hernández, Isidore Isou, and Marguerite Duras became a priority in my viewing habits. (Of course, these filmmakers shared a history of transnational movement that was quite unlike my own, but like enough in spirit for a more sophomoric version of myself to become interested in the peculiarities of their cinema and the particularities of their histories.) It was also around this time that I was finally forced to read Gilles Deleuze’s Cinema 1 and 2 as part of my studies. Apropos of French cinema, the following line had a lasting impression: “It is the French school which emancipates water, gives it its own finalities and makes them the form of that which has no organic consistency.”

The quote arises from Deleuze’s discussion of montage in Cinema 1, and his identification of distinct montage styles across different film industries. The details of this are not worth delving into here, but what is is Deleuze’s invocation of Jean Grémillon and Jean Vigo to elucidate that “a general predilection for water, the sea or rivers” runs deep in French cinema. Think Stormy Waters (1941) and L’Atalante (1934), respectively. And so, perhaps because water animates French cinema, it makes sense it could culminate in a wave, and that that wave would cause a ripple effect across the globe, inspiring a free-flowing approach to filmmaking that emphasizes the artist’s hand in film production. And, if we were to push this metaphor any further—beyond what should be allowed—we’d become aware that focusing on one wave, on the New Wave, excludes a whole lot of other waves, ripples, and wavelets.

A couple years ago, the French film critic and historian Jean-Michel Frodon toured a film series titled "Forgotten Filmmakers of the French New Wave” across the United States. It included the work of directors like Marcel Hanoun, Jean-Daniel Pollet, and François Reichenbach, among many others. (In fact, some of the filmmakers in this program have grown in popularity since their exhibition in this series: Jacques Rozier, in particular.) Frodon’s aim was “not to question the singularity and significance of what transformed French cinema—and cinema language at large—in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but to illuminate it differently” in such a way that the expression nouvelle vague captured a “broader phenomenon of generational renewal throughout the country.” In essence, his program proposed that the New Wave went beyond the “Magnificent Nine” so often associated with the movement, and that it involved their precursors (Georges Franju and Alexandre Astruc), their contemporaries (Pollet, Rozier), and their successors (Philippe Garrel, Paul Vecchiali, among others). It was the wave as a continuum, rather than an instance.

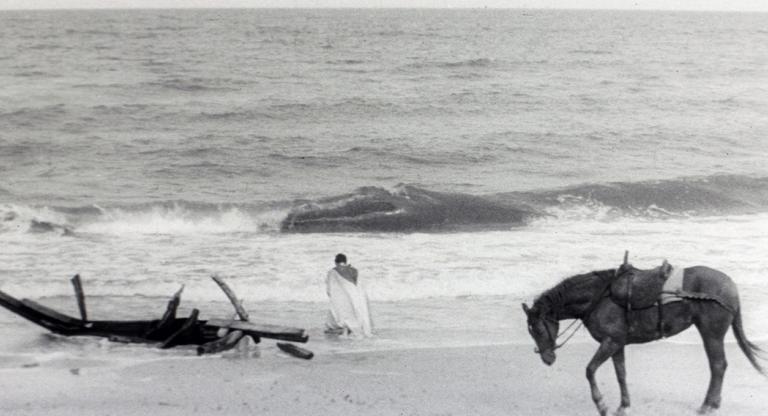

The reason I bring all of this up is because I have been noticing a growing interest on behalf of New York audiences and greater risks on behalf of our city’s programmers in relation to these “forgotten filmmakers.” Of course, these viewing practices and curatorial moves also fall into a continuum. In 2014, Anthology Film Archives organized a retrospective around the work of Marcel Hanoun; in 2023, Graham L. Carter and Bingham Bryant put together “Paul Vecchiali, Producer: From Jeanne Dielman to Diagonale”; earlier this year, Harvard Film Archive presented “The Reincarnations of Delphine Seyrig.” But, even more recently, AFA screened Guy Gilles’s Earth Light (1970, pictured at top) and then New York University’s Espacio de Culturas put on a free show of his first film, Love at Sea (1965). Elsewhere, L’Alliance New York has been running a comprehensive tribute to the French filmmaker Yannick Bellon, and Light Industry is getting to ready to present two films by Jean-Claude Biette to celebrate the latest issue of Narrow Margin, a new quarterly film publication dedicated to “under- and mis-appreciated cinema.” For the first time in a while, French cinema has started to show off its many faces.

To make sense of the growing interest in these French filmmakers, I reached out to Pierre Jendrysiak, a member of the French film publication Débordements’ editorial committee. “These filmmakers that you’re talking about—Guy Gilles, Yannick Bellon—are very little known in France; even just a few years ago, most of their films were not available,” said Jendrysiak. “The first time I heard of Guy Gilles was during lockdown on this big Facebook group called la loupe; people kept asking, ‘Do you have links to films by Guy Gilles?’ and nobody had them.”

This group, which included such luminaries as Nicole Brenez, yielded a renewed interest in aspects of French film history that had long been forgotten, with critics, cinephiles, and historians sharing old DVD transfers and files of films that were deemed more or less lost by most. If I'm not mistaken, la loupe is where contributing writer Steve Macfarlane first read about the films of the French-Martinican director Julius-Amédée Laou, which he has since programmed and championed states-side and abroad. “Guy Gilles, like Yannick Bellon and Reichenbach, became passwords among cinephiles in the last few years,” said Jendrysiak. “These names were part of a closed circuit and were not open to new cinephiles because we couldn’t see their films until a few years ago.”

Detailing her first encounter with the work of Yannick Bellon, L’Alliance New York’s Film Manager, Chloe Dheu, recalled feeling flabbergasted about the fact that she’d never even heard of Bellon until very recently. “She was completely unknown to me,” she said. “It’s still kind of a mystery to me why she’s not as recognized.” Similarly, when I asked Jendrysiak about the filmmaker, he said: “What I know about Yannick Bellon is that she exists.”

It’s an odd historical lacuna, as history suggests she’d at least be recognized through association; Bellon was the daughter of a famous French photographer, was involved with Jean Rouch, and worked with the likes of Chris Marker, Bulle Ogier, and Nathalie Nell. But that she is not remembered for her cinema is even more astonishing as it is both confrontational in character and adventurous in style. Of course, that might be part of the problem. Her films were criticized for their frank approach to topics such as divorce, queerness, and rape. “She has a modern eye and she really played a role in bringing modern topics to the front of public life through her work,” Dheu said. “Her militancy is in her films.”

Except militancy isn’t necessarily mainstream. Beyond that, it’s important to consider that Bellon was a woman. Moreover, she was deliberately removed from the New Wave. She treasured her independence and worked to safeguard it throughout her life, even if it resulted in critical or commercial loss because she wasn’t part of the in-crowd or appeasing audiences with accessible stories. “Yannick Bellon was a woman,” said Jendrysiak. “The ones who became famous were white, straight guys.”

This might also explain why the films of Gilles were lost, or those of Vecchiali have remained little seen. (Well, this is and the rights issues that so often trail the dead.) “It is quite important to state that a lot of the people we’re talking about were gay or bisexual,” Jendrysiak told me. “There’s a very famous interview with Serge Daney in which he says that while it was not heinous, there was a kind of internalized homophobia in the New Wave and I think it stayed with the Post-New Wave too—with Garrel and Eustache.” Meanwhile, the openly queer films of Bellon, Gilles, and the directors associated with the production company Diagonale put forth another vision of French life—one that, sadly, isn’t being recognized, until now.

Speaking about the filmmakers involved in Diagonale, Joshua Peinado, member of the editorial board at Narrow Margin, told me the following: “They were all on the margins of sex––whether as queer women or men.” Films like Vecchiali’s Once More (1988) and Marie-Claude Treilhou’s Simone Barbès or Virtue (1980) make this abundantly clear in their honest depiction of queer life; one expounding on a condition of loneliness, the other showing the joy (and hardship) of community. “Their queerness was an aspect of their marginalization,” Peinado continued. “Their films weren’t distributed in the same way other films were, which was something that Vecchiali was very upset with.”

Yet Diagonale, more or less, kept together at first. “It was really a band, a strong group,” said Jendrysiak. The brainchild of Vecchiali, Diagonale was both a production company and allegedly a catering company; the idea being that if the films didn’t make enough money, the catering would cover the losses. This logic also applied to the films Vecchiali produced. “The idea was, let’s make 10 films with very small budgets, and if it doesn’t work, it’s fine because at least one of them will make money to help the others,” Jendrysiak explained.

Among the filmmakers who made their first films with Diagonale were Gérard Frot-Coutaz, Jacques Davila, Jean-Claude Guiguet, Treilhou, and Biette. It’s the latter whose films are being shown to celebrate the launch of Narrow Margin’s second issue. “Both of the films [1982’s Far from Manhattan and 1995’s The Complex of Toulon] we’re showing at Light Industry have this fascination with the actor,” said Hicham Awad, member of the editorial board of Narrow Margin. “There’s been a really bitter legal fight over who owns the rights for a lot of the Diagonale films, and screening fees are prohibitively expensive for a lot of these films,” Peinado said. “But it wasn’t the case for these two films, which are luckily two of the greatest films in this movement.”

One can anticipate a full house at Light Industry for these screenings—a conjecture I make based on how full the screenings of Gilles’s films have been, and the general enthusiasm surrounding the work of Bellon at L’Alliance New York. And for those in attendance, what awaits is an opening unto a new current in French cinema. As one wave washes away, others reveal themselves. For the programmer, the opportunity to take a plunge into the deep waters of French cinema announces itself once more; for the audience, the knowledge that new gems will shore up at the cinema should guarantee a sense of peace and excitement.

Correction: This article previously mis-identified Chloe Dheu as "Assistant Film Programmer at L'Alliance New York." She is currently the Film Manager at L'Alliance New York.

Special thanks to Hicham Awad, Julia Catacutan, Chloe Dheu, Pierre Jendrysiak, Jake Perlin, and Joshua Peinado.

Feedback Loop is a column by Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer reflecting on each month of repertory filmgoing in New York City.