“Be careful,” a friend warned when I said I’d be spending the weekend at Crossroads, the Bay Area’s annual experimental film festival. “Sitting in the dark that long isn’t good for you. You’ll, like, forget you have a body.” But if my vitamin D intake suffered, my proprioception did not. Instead, the hours I spent watching artist-made films at the Mission’s Gray Area served as a welcome reminder that I had hands, sit bones (the theater space: phenomenal; the chairs: uncomfortable), and, in one memorable instance, a gag reflex. Now in its 14th iteration, Crossroads has long served as a platform for moving-image work that tests the limits of what filmic and video technology can do. This year, it also served as a testament to the embodied intelligence at work behind, around, and sometimes within the machine.

Curated with a canny sense of rhythm by the SFCinematheque director, Steve Polta, Crossroads’ ten programs featured works from 61 artists, roughly half of whom live and work outside the United States. Those who had traveled over state lines to attend the screenings in person came from as near as Mexico and as far away as Milwaukee, and their presence in and around Gray Area’s hollows made the weekend feel elevated yet collaborative, like a meeting of the world’s coolest AV club. Oxymorons aside, the most striking of the weekend’s prodigious selection highlighted a similarly hands-on approach in both subject matter and style.

Closing the first night, Elena Pardo’s propulsive, three-projector film Pulsos Subterráneos (2022) made palpable the divergent experiences of two mining communities in Oaxaca and Zacatecas, Mexico. In Oaxaca, organized resistance has allowed the municipality of Calpulálpam to prevent the corporatized reopening of old silver mines. Meanwhile, in Zacatecas, local communities have been fleeced by industrial mining activity. Homing in on the human face and the ecological world as registers of labor power’s varied forms, Pardo’s film wonders how such distinct expressions of resistance and exploitation are made manifest. Screened simultaneously across three overlapping 16mm projections, Pardo’s work is both expansive and occasionally claustrophobic. As we move from wide landscapes deep into one of the mines, the film winnows into a single beam of light, as though the walls are closing in. On the other hand, in pulling apart the lap dissolve until the spaces between images become actual space, Pardo concretizes the disparity between Oaxaca and Zacatecas, and the time that has passed since the world was the green thing at the film’s outset, as opposed to the arid rock upon which she closes.As Pardo ran the projectors, and once ran up near the screen to communicate with local musician Guillermo Galindo, who scored the film live, Pulsos Subterràneos became as much about its own working into being as it was about its subjects being worked over. In a video version shared as a press screener, there is a brief look at Pardo behind spooling projectors, centered in the space between two shots of hands chipping away at stone.

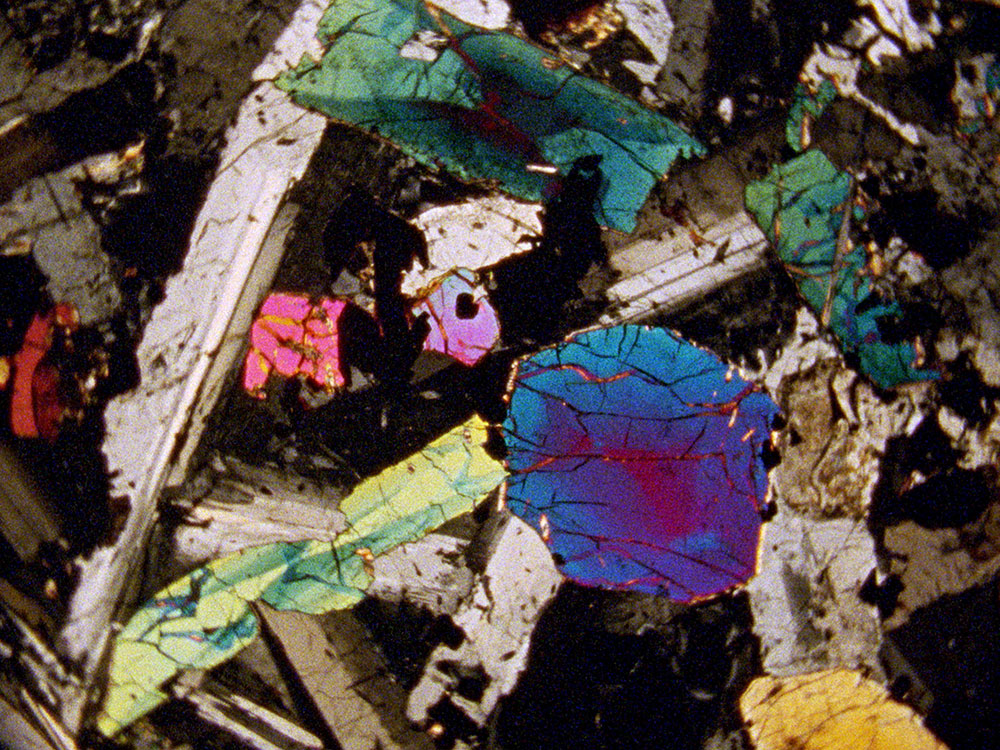

Pardo’s wasn’t the only film that incorporated an element of live performance. Scott Stark’s Music in the Air (2023), for example, reimagined the jump cut through the use of a propeller-rigged projector, its speed made variable by turning the knob of an electronic rheostat. Nor was Pardo’s the only film that took up rocky landscapes and representations of labor. In Deborah Stratman’s Last Things (2023, pictured at top), making its Bay Area debut after premiering at Sundance, the beginning and end of all life on Earth is reimagined through a stony lens. Human subjects are replaced by chondrites, their seismic reformations narrated through a combination of texts by Clarice Lispector and J.-H. Rosny aîné. It’s a film for anyone who has kicked a rock down a sidewalk and felt they were following its direction, rather than the other way around. Screened early on Sunday to an animated crowd, Stratman’s emphasis on the nonhuman ebbed into a wondrous expansion of what “the human” might mean. Eventually even the rocks, established early on as archivers of cosmic history though they remember nothing, are marked by the shadowed hands of long dead cave painters. Siegfried Fruhauf’s Cave Painting (2023), screened later in the day, highlighted the psychedelia inherent in this image (hallucinogens hail from the Bronze Age), crafting a Kubrickian trip through handprints and hand-painting that was unexpectedly echoed that evening in the credit sequence of Morgan Quaintance’s Repetitions (2022). Tuning into the push-pull of sick days as the driving beat behind tired bodies and labor history, Quaintance’s film ends on a hand that brushes over granite again and again, leaving behind nothing but the anticipatory memory of its own reprise.

Mark-making defined the festival’s penultimate selections, but it could have described nearly all of the programs over the course of the weekend. Chiara Caterina’s spectral L’Incanto (2021), which braids together interviews with five Italian women who have been in some way proximate to violence, proposes even death as a kind of lingering presence: “Maybe to protect oneself. To leave some good memories behind, I should . . . get rid of me.” This idea was reaffirmed, in a less morbid mode, with Saturday night’s memorial program for Kenneth Anger, who passed earlier this year. Following a 16mm screening of his 1953 marvel Eaux D'artifice, the retinal afterimage of Anger’s famed fountain streams remained vivid even once the screen had darkened.

In some ways, writing about Crossroads feels like falling short. This is not only because the films are so numerous and so wholly in their own language, but because the experience of seeing them live, in a moment still shadowed by the pandemic’s effects on in-person exhibition, is difficult to translate into words. A few films, particularly Christopher Thompson’s Damp Moss (2023), Angelo Madsen Minax’s Bigger on the Inside (2022), and Vincent Grenier’s Moonrise (2022), were suggestive of this haptic weirdness—the collapse between the physical, the natural, and the digital realized, in the last instance, as rainfall set to the sound of tapping laptop keys. Perhaps I should take my cues from the woman down the row from me on Friday night, who threw up during Brent Coughenour’s flicker effect film. It was part of a project called The Sick Sense (2023). I think, with her stomach in her mouth, she might have understood it better than any of us.