Today Screen Slate is thrilled to announce its first expansion to the West Coast with Screen Slate San Francisco Bay. We’re officially launching later this summer, and you can sign up for the forthcoming newsletter now.

To mark the occasion, we invited UCLA Film & Television Archive programmer and Camera Obscura co-director Amanda Salazar to speak to Anita Monga about Bay Area film culture and the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, which runs today through July 16.

When I started programming in San Francisco, I realized that it all overlaps—the histories of the festivals, the theaters, and the employees are all intertwined. Most people that were once involved with these events and spaces are still in the Bay, supporting film culture. The scene is rich with stories and connections, a small-town feeling in a big city. Anita Monga is one of those programmers who has connected many such pieces, leaving a lasting impact on film culture in the region. A Northern California native, Stockton born, Anita has been a part of the Bay Area film scene since the late ’70s. After years of booking theaters, she has held the position of Artistic Director for the San Francisco Silent Film Festival since 2009.

When I learned Screen Slate would expand to cover film events and moving-image culture in the Bay Area, Anita immediately came to mind. Not only because of her experience and understanding of the Bay Area film scene but also because she is a gracious, discerning curator that cares deeply about the filmgoing experience and the future of film exhibition. We sat down to talk about the upcoming program of the Silent Film Festival—a unique event dedicated to the presentation and preservation of silent cinema—and also got to discuss her own history and thoughts on Bay Area film culture today.

Amanda Salazar: I'm so thrilled to be in conversation with you, Anita. You have been such a supportive, enthusiastic, and passionate guiding force in the Bay Area film scene for decades. So I would like to start at the beginning, which is with your journey to this work. How did you get started as a film programmer?

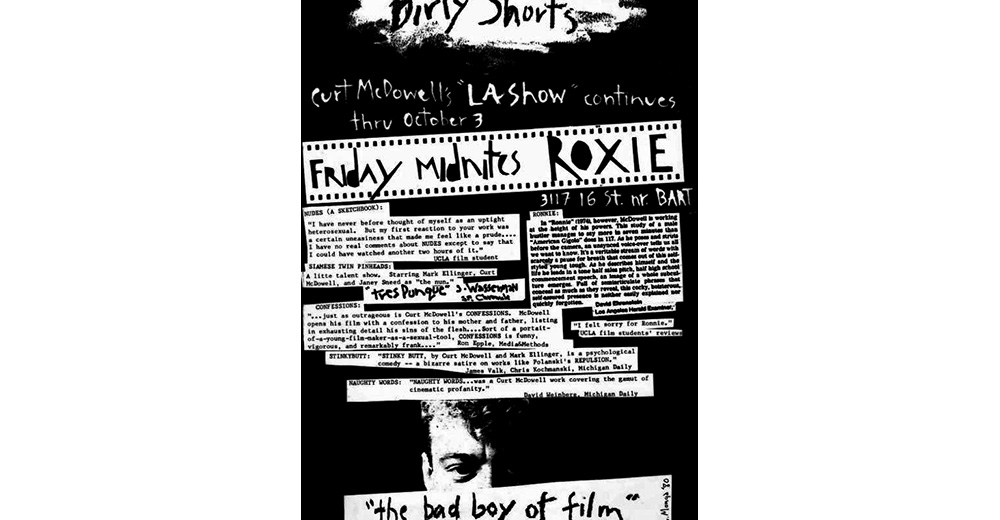

Anita Monga: I started at the Roxie Cinema, which is now called the Roxie Theater. I came to the Roxie through underground filmmaker Curt McDowell. We just had an instant rapport, when we met at a ceramics factory where we both worked. Curt had a collection of short films, and I had the idea to put them together and call them “The L.A. Show." So we went to the Roxie, and asked the owners—who happened to be Curt's partner, Robert Evans, and my future partner, Peter Moore—if we could have the theater on Saturday nights. We put on the show, we do all the advertising, we do everything. And they said, “Yeah, sure, go ahead.” And that's how it started.

AS: And what year was this?

AM: I think it was 1979 when Curt and I put on our first show at the Roxie. So when Peter left for New York, I just stepped into programming the Roxie with Robert. Then in 1984, the Renaissance Rialto used to run the York Theater on 24th Street. Now the building is called the Brava Theater, but at the time it was a repertory house. Ray Price, who ran programming for all of the Renaissance Rialto chains, asked me to come and do the York theater. So I left the Roxie and did the York. I started working with Renaissance Rialto and then they took over booking the theaters when Mel Novikoff was dying and then Ray asked me to book the Castro Theatre, which I did. Out of all the theaters that I’ve programmed the Castro was the closest to me. Every theater has its own personality and things that it can and can't do well. And the Castro did well with things that I most loved.

AS: What were some of those things that you most loved?

AM: You know, the Castro was able to do classic cinema and all of it, the history of cinema. The York was particularly great for very political stuff and documentaries, but there were things that would just die there. And the Roxie was really fun because you could program things that didn't need a huge crowd to work. So that was such a freeing thing. But the Castro—there was something about it that just jived with my sensibility.

AS: I'm really curious, thinking about your early stages of programming, if there was something that you learned as you were figuring it out that has stuck with you today, decades later.

AM: In 1988, when I came to the Castro, it was at the height of video. Everyone said, “You can't do that, everything’s on video,” and I didn't listen to that conventional wisdom. The Castro took off like gangbusters. In fact, I felt that video allowed people to educate themselves in a way that made them really interested, really dig deep into a filmography. I remember that kind of “trust your own instinct” about what people will be interested in. Also the really big thing, and I used to say this all the time: San Francisco is the best audience. It is such a great, intelligent, enthusiastic, and—willing to take a chance. If you keep faith with that—if you, as a programmer, don't insult their intelligence—they'll go along with you for things that they might not have ever thought they wanted to see. And I'm not saying that everything at the Castro, or any of the theaters, was everybody's cup of tea, but you have to not insult their intelligence. I think that's the most important thing: to have that correspondence with your audience, that you try to keep faith with the audience.

AS: I love that. San Francisco is such a special place for film culture, in its history, and the ways that filmmakers filmed it, and movements that started here. It feels like the San Francisco festivals are in dialogue with other film events around the world.

AM: Well, I do think it's so because the audience is so great. Now, there's a correspondence between why the audiences are so great. San Francisco International is the oldest film festival in the [Americas]. There's a great responsibility. They cultivated this audience, they cultivated this kind of intelligence and film literacy. And all the festivals that followed also did. So it's hard to say which came first. San Francisco has always been a kind of place where people will take a chance.

AS: I really appreciate your saying that, because as someone who came to the city later, it's fascinating to think about that journey and the audience. To me, there's also something about the proximity to art and culture that we have to seek it out. So when it makes its way to the city, it feels so special.

AM: I am such a fan of programming other programmers. I'm a fan of people taking me along, because I don't necessarily know what to look for. I'm so appreciative of Bruce Goldstein at Film Forum, and the Criterion Channel, and people who give it a very personal, very human touch. I think that's an important thing for a programmer to be: human. As somebody who's been annoyed countless times by Netflix's suggestions based on your “blah blah”—you don't know me!

AS: [laughs] You don't know how I'm feeling today, Netflix!

AM: It's so interesting to see. Because all the algorithms are leading to: if you like Andy Warhol's Bad, and you like Kubrick's Barry Lyndon, then of course, you will like some piece of shit that we're recommending. But it's not human.

AS: Well, speaking of that humaneness, given that you have worked with so many organizations and institutions, ones that the city is now defined by, could you talk about what that has meant for you in terms of creating film culture or building upon the film culture that was in the Bay Area already?

AM: I worked with all the festivals who came to the Castro, so I have so much admiration for all the film festivals and the little audiences they bring in. You know, the films kind of take a back seat to the party of it, to the community of it. Not to say that the films are not important. They definitely are.

AS: There's an energy to it, and I could say this about Silent Film Festival: there's an energy that you create, an environment that is beyond just the moving image on the screen, that adds to the experience

AM: When you go into each Festival, the varied audiences that they can bring in are more difficult to reach for a general program. And at Silent, I knew there was something enchanting about being in the auditorium with live music. It is so extraordinary. Out of all of the festivals [the Silent Film Festival] is probably the most difficult to get people to come to because people have a feeling like silent films are old, and they are black and white. And people have often seen examples of silent films on YouTube or something with shitty music and done in the wrong aspect ratio, the wrong frames per second. So there are all kinds of things that go against [that type of] film. I feel like— Isn't it the Catholic Church that said, “give us a child at eight . . . ”? I feel that about a silent film. If we could get people in there, you can't not be enchanted by the beautiful images on screen with music. It's so amazing.

AS: Anita, as a convert, as someone who arrived in San Francisco and did not know about it, it's now truly an event that I demand people come to. It doesn't matter what you see. I've found it actually re-energizes your belief in film.

AM: I really do think so.

AS: The San Francisco Silent Film Festival has established itself as a must-see event that is unlike anything else in the Bay Area and the country. Could you give a history of the Silent Film Festival and also what makes the event so special?

AM: The festival was started by two film lovers, Melissa Chittick and Stephen Salmons. The Castro had the Mighty Wurlitzer; the Mighty Wurlitzer was the premier theater organ in the country. And so it was a simple thing to do silent film there because there was this built-in, concert-ready Mighty Wurlitzer. So I used to program these vertical series, your Noir Mondays, Silent Tuesdays, and it was always popular. Anyway, Melissa and Steve used to come in and they both fell in love with the silent era. These two would go down the lines of people waiting in line to get into the silent shows and say, “If we had a silent film festival would you come?” They were very cautious—very, very deliberate. And it took them a couple of years to do it. But then they had their first event in 1996. And then, in 2005, I believe, Melissa, who was functioning as the executive director, stepped down, and Stacey Wisnia came. Stacey was working with Steve, and she had brilliant ideas. And then in 2009, Steve left, and Stacey came to me and asked me if I could fill in for this one. I have a long history of just filling in until something happened! So I just helped with getting the 2009 festival together and then I stayed. We just expanded and we took it into the 23-to-29-program festival that it is now.

Silent blends the San Francisco audience with the international audience, with people coming from archives around the world. That has made it really special. Also, in the very beginning, it really was just using the organ, and now it's ensembles and really different kinds of music.

AS: There's also such care of the history and the record of what you're doing every year. I'm specifically talking about the programs that are created for each year—

AM: The book!

AS: The book! This book is not just a film program; it has photos, essays, historical contexts on each presentation . . .

AM: We put a lot of effort into the original essays in the book and I really need to give a big shout out to our editor, Sherry Kizirian, who lives in Rio de Janeiro.

AS: You ensure that a physical publication is incorporated into the production every year, when other festivals and events are moving toward just digital documentation. There's something really beautiful about coming to your festival and receiving this kind of artifact that is so carefully constructed.

AM: We really like the book. Other festivals still put out catalogs, like our compatriots at Pordenone, Bologna, and Noir City. We like the physical object. And I should mention the slideshows that we do. There's a lot of original scholarship that goes into the sideshows and the book. It's all original stuff adding to the world's understanding of this kind of pivotal moment in film history. Maybe because we're harking to some previous era, the analog means a little bit more to us. After the festival [the book] goes to archives around the world, and to libraries. We really value the digital and value our ability to reach people in other places, but I just like the book. I'm glad you like it too.

AS: I love it. It's a gift we all get when we enter the theater—when you arrive and you get this hefty, beautiful book.

AM: Not too hefty, it can be carried around!

AS: [laughs] Yes! When you're not working within the structure or confines of film submissions, how do programs like this come together?

AM: If it were just [about] pleasing somebody like me, it would be so depressing! It's really [about] keeping in touch with the international archives and people doing restoration work. Now San Francisco Silent has also thrown our hat into the restoration ring. So we're always looking to partner with archives around the world, to help restore titles that we find interesting and return them to audiences. For instance, Stark Love [1927], a title by Karl Brown, has been on my list for years, and this year it went into the public domain, so we were able to easily access the 35mm from MoMA in New York. I thought we had to do it this year because we have no idea what the future is going to be, in terms of 35mm. So, in essence, it is trying to balance the stuff that has been on my list for a long time with what is new. And actually, just to balance the kind of tones. Trying to inject funny into the day is important, while trying to balance films from around the world and different styles of filmmaking. We want people to come into the theater and sit there the entire day. Also, we have to balance the music; working with the musicians and pairing the films with the musicians. But we do not micromanage the music at all. Once we have a feeling that the film ensemble or the composer can do the film, we're like, “Do your magic! We trust you.”

AS: Does this mean that you're sometimes witnessing the score for the first time with the audience?

AM: Yes! It makes it special. You know, there's always a ton of stuff happening during the festival, but there are certain films that I'm just sitting at the back of the house watching this film with the rest of us.

AS: It is so rare for us to have moments like that, where not only are we collectively gathered, but we're all witnessing something for the first time.

AM: It’s a once-in-a-lifetime thing. You might be able to go see it, but it will change. Each performance is one-of-a-kind. I do love that ephemerality of “You miss this, you missed it,” you know?

AS: And, to your point, when a different audience comes in, it's a different feeling each time. Speaking of that performance, are there any highlights you'd like to call attention to for this year's program?

AM: Yeah, there's a film that I knew nothing about—with Maud Nelissen, who is conducting our closing night film—The Merry Widow [1925], which people shouldn't miss. Maud introduced me to a Czech film, The Organist at St. Vitus Cathedral [1929], which is so beautiful and moving and has noir elements. Czech film in the silent era is pretty amazing. The Czechs knew how to do it, the Germans knew how to do it, the Swedes knew how to do it. There’s The Dragon Painter [1919], which is one of the San Francisco Silent Film Festival restorations. There was a restoration in 1980 that kind of formed the basis for this restoration. I'm really looking forward to that. Oh, don’t miss A Daughter of Destiny [1928]. We're giving our 2023 award to Stefan Drössler. He restored this film, and it is almost indescribable. It's a German film starring Brigitte Helm and Paul Wegener. He's a mad scientist and he wants to do an experiment that tests nature versus nurture. It's so insanely wonderful.

AS: Oh my gosh, what a wild ride.

AM: It is pretty great. From UCLA I’m really looking forward to A Midsummer Night's Dream [1909] with Sascha Jacobsen Quartet that is going to accompany that and Up in Mabel's Room [1926], which is such a hoot. Also, Man and Wife [1923]—this is a really amazing plot filled film.

AS: It is so obvious, Anita, your love for each one of these programs. So I encourage readers to come all day because of the journey you're going to take us on. I just want to thank you for putting together such an incredible program. The Silent Film Festival started at the Castro Theatre, it is currently at the Castro Theatre, you worked at the Castro Theatre, and [the Castro] has been the talk of much of the community for the last few years since it is closed during Covid. It then reopened under a new private contract. The sacred venue is going to be operated differently with a planned remodel that has caused tension within the community. My question isn't really about the feelings or the politics behind that, but about change and your perspective on change. Given your great knowledge of the city as venues have come and gone over the years, the Castro clearly holds a very special place for you and the community. How do you approach this change? How do you adapt, or maybe embrace these moments that feel so big, when we're in the middle of change in San Francisco?

AM: Of course, I'd rather nothing ever change, ever. But as soon as we found out that this was happening, and the plans for changing the orchestra, we just went to Another Planet Entertainment and tried to get them to shift their thinking a little bit. We give them a lot of credit for listening to us. They made a lot of changes to their original plan that make it more workable. So we have no real idea of what it's going to be like. I just hope that the theater will be accessible for filmgoing.

AS: Yeah. And for the broader question about your experience in the city, does it cause you to reflect on changes of San Francisco? Or how do you feel about this?

AM: I mean, the Castro is just like one tiny element of what's happened in film culture in the Bay Area. All of the theaters are closing—like the Embarcadero closing, and then all of the single-screen houses are gone. That's been years in the making. So it is really difficult to find places to see movies now. I give it to the Roxie; they've really risen to the occasion and they're doing really interesting stuff. But there could be three more places like that in San Francisco. The pandemic did a lot of damage to filmgoing, and I get that people don't necessarily want to go back into the theater to see run-of-the-mill stuff, but there is pretty special stuff out there that they would come to see. I feel bad that going to the movies is not so easy anymore.

AS: It’s interesting how that discerning, adventurous audience we were talking about needs to gather again, and that's where I think Silent really flourishes. Because it is this special place of film enthusiasts and cinephiles and it also engages and allows new people to enter into the space as you welcome them to a new experience. I'm hopeful that Silent has a very successful year and that it allows people to be able to engage in that adventurous side a little bit more. Because if they don't, then the spaces will go away. They will continue to go away. Participation has to happen on both sides. It's an interesting time in the Bay, for sure. Where are you placing hope and excitement in film culture specifically when it comes to the Bay?

AM: Well, I do think the Roxie is a really hopeful, hopeful glimmer and I think there are other people doing film program stuff. I am not not hopeful. I'm hopeful!

AS: You are! You're an eternal optimist!

AM: But I do think that it's hard, too. So many people—and I, too—bemoan the closing of theaters. But I do think something exciting can rise out of the ashes of a closed theater.There's a whole generation of people who are interested in doing interesting things. These young cinephiles are doing it. When the Roxie allowed Curt and me to do our show at midnight—that kind of stuff continues to happen. I think that something that I can't even foresee is going to happen. There are enough people here that value this culture, value filmmaking, from the earliest times, through the mid-century, to the next mid-century. I can't envision what it will be. It is not mine to do. Have at it!

The San Francisco Silent Film Festival runs at the Castro Theatre through July 16.

Learn more about Screen Slate SF Bay, and sign up for the forthcoming newsletter.