On the world stage, the cinema of Los Angeles is largely synonymous with Hollywood’s racialized and gendered structural exclusions and the reproduction of white supremacist imagery. In retaliation, a wave of L.A.-based Black independent artists and collectives, alongside diasporic networks of Black and anti-colonial filmmakers, reframed and reimagined what Black life looks like on screen. The work of Black women such as Camille Billops, Kathleen Collins, Maureen Blackwood, Safi Faye, Zeinabu irene Davis, and Julie Dash disrupts dominant cinematic representations of Blackness, and the constraints of narrative in general, by centering Black womanhood. Cauleen Smith’s artmaking is grounded in continuing that lineage, and her masterful first feature, Drylongso (1998), pushes the boundaries of Western cinematic genres and the canon of American independent filmmaking to attend to the mundanity of Black intimate life.

The film is inspired by the oral reportage of the same title gathered by the African American writer and cultural anthropologist John Langston Gwaltney, a collection of transcriptions of interviews with working-class Black people, many of whom refer to themselves as “Drylongso” to describe their class and/or social status. Shot on 16mm on location in Oakland, Smith’s Drylongso visualizes Black life in the midst of what filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha names “entangled temporalities.” By mixing genres (coming-of-age story, murder-mystery, horror, and romance), Smith creates a representation of ordinary Black life. As Richard Powell notes “a significant segment of black portraiture stands apart from the rest of the genre because of the historical and social realities of racism.” The film defies narrative conventions to convey Black life rather than represent it, localizing the history of Black diaspora in pre-gentrification Oakland.

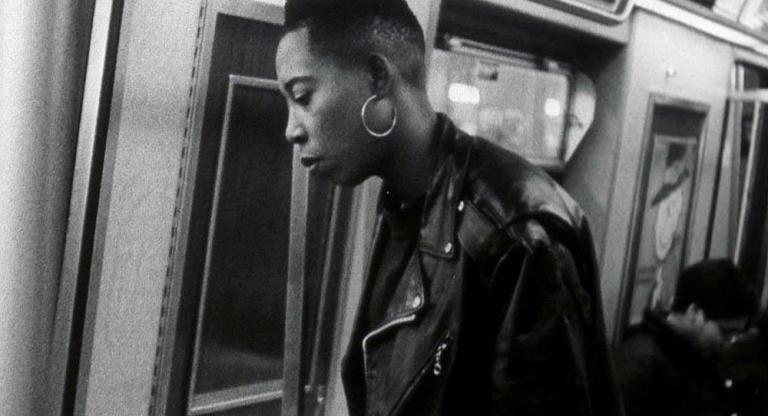

The film follows Pica (Toby Smith), an art student who uses Polaroid snapshots to document the Black men in her community, who are most under threat of violence. “I’m capturing and preserving their image,” Pica says. “Some kind of evidence of existence.” As Pica and her friend Tobi (April Barnett) navigate what Smith names a lot of “different kinds of jeopardies,” a bond of kinship forms out of their shared positionality to predatory violence and disposability. In breathtaking scenes of radical care and tenderness, Pica and Tobi friendship guide each other through loss, love, heartbreak, and gratuitous violence.

Drylongso remains Smith’s only feature film. When it came out in 1998, the film screened at the Sundance Film Festival and South by Southwest, but it never found major distribution. Like many other pioneering Black women filmmakers whose works have been neglected, buried, and unseen, Smith’s directorial debut did not receive the recognition it deserved—until now. The film has now been restored and is being distributed by Janus.

Matene Toure: You made Drylongso while earning your MFA at UCLA. The school is associated with several Black independent filmmakers and collectives, notably the L.A. Rebellion. Did that history influence your filmmaking in any way?

Cauleen Smith: Before I got to UCLA, I was studying at San Francisco State University, [where the film department was] very experimental, self-reflexive . . . and documentary based. There I was influenced by Trinh T. Minh-ha and her work. Also, Larry Clark, who was part of the L.A. Rebellion. He was one of our cinematography teachers and trained us to think about speed, economy, and aesthetics as one operation. Not so much like always functioning as if you don't have something, but understanding what you can achieve with what you do have. That was highly influential. When I got to UCLA, I’d always been a big Cassavetes fan, and [Akira] Kurosawa and [Krzysztof] Kieślowski started emerging at that time. But mainly I was influenced by the independent filmmaking wave that was taking hold in the early to mid-’90s, starting with She’s Gotta Have It [1986]. I have the first edition of [the book, Spike Lee’s Gotta Have It: Inside Guerilla Filmmaking] still. I read that book cover to cover many times because it was about how to make an independent film with nothing. Julie Dash was another major inspiration. When Daughters of the Dust [1991] was in theaters, I watched it repeatedly and was profoundly influenced by the way in which she framed women and the way in which she had them in relation to each other in the frame. I'd never seen [that] before and rarely ever see it now.

MT: In Drylongso you explore everyday realities of violence in Black communities. The title of the film means mundane and ordinary in Gullah. Can you discuss the thinking behind using Pica’s character to explore the mundanity of violence in Oakland?

CS: I thought of myself as telling a story about two girls trying to live, and I created the world that they lived in. It's true that the title of the film is Drylongso, which is a word that means “everyday people,” and that's who I want to make movies about. Everyday, regular Black people are constantly operating in environments where there's a great deal of psycho and social and economic violence and a lot of other stuff going on all the time. But they are just functioning and having families and falling in love and doing their jobs and getting into trouble and just living life. That's what I was making a film about: people living. I wasn't making a documentary that was supposed to be about revealing the pathologies of the Black community.

MT: The protagonist, Pica, uses an art-school project as an opportunity to document the missing and murdered Black men in her community. You’ve talked about how during that time “Black men as an endangered species” was a prevalent idea in the culture, especially in hip hop. Can you talk about some of the ways you use craft and production to highlight that moment?

CS: That's where Pica's character comes in. She is obsessed with that reigning popular discourse of the time, this idea of the Black man as an endangered species. And she is invested in that issue both consciously and politically and maybe through some aspects of trauma that we don't necessarily explore in the film. She has this obsession of taking these photographs and explaining why she's doing it. And then she has direct adjacency to this violence by losing Malik. She is right around the edge of these pervasive and almost mundane conditions that most people are always dealing with.

Hip hop was all about that. There was also this Afrofuturistic—I mean, now you would call it hotep-y—hip-hop that was about Black kings and queens. But her character was immersed in that philosophy. If you look at the art direction in her bedroom, all the images except for the comic book that she's reading are patriarchal centered, from Bob Marley to Jimi Hendrix. I think even Marcus Garvey is on the wall. She happens to be reading this one comic book, which I was obsessed with at the time, by Frank Miller, called Martha Washington Goes to War. If I could have afforded the rights, we would have featured that image more prominently because that was an additional aspect of her character that I wanted to depict. But Frank Miller was just like, “You can show the comic book, but you can't make a giant poster.”

I think most people don't even pick up on the comic book that she's reading, but it was a very important clue about her intellectual and cultural universe. In the ’90s everyone was a little bit too close to that stuff. It was a very difficult period of a lot of violence, what the media likes to call “Black on Black crime.” I think that what was frustrating for me when the film came out: people almost treated it as if it was a documentary, as if I was only focused on the pathologies of the Black community, and no one cared about Pica the character.

Now when I talk about it, I try and focus on Pica the character, not about all the pathologies that people like to use Black media for. If Black movies don't teach white people something about the Black community that they feel like they can use and weaponize later, then they're not interested in it. Even a simple film that's about a friendship between two girls, people are desperate to have it be about this or that political issue. In the ’90s it was the endangerment of Black men. In 2023, it's missing girls and women. So people will pick up on some issue and pull it out and try and use the film as leverage to talk about that. But this film is a cultural object. It's entertainment, it's a story, its storytelling, it's aesthetics, it's craft.

MT: That’s a great point, it’s interesting how Black cultural production is used or weaponized against us.

CS: All Black films are still used that way, and the questions are always geared that way. Like, Talk about this social problem, talk about that social problem. We’re entitled to have intimate, complicated relationships. We’re not symbols for social problems.

MT: I love the scene where the little girl comes up to Pica and hands her the photograph of her brother that has passed away and asks her to build a shrine. What were the intentions behind that scene? It is such a tender moment, and it is filled with a lot of care.

CS: Once she starts making this artwork in a public space, and once the community understands what she's doing, they become invested in it and want to participate. Because of the way Pica was making her work in the first place—asking people for their image so that she could build her body of work—she's grateful for that kind of engagement and exchange. It doesn't become a kind of artwork where the artist is pronouncing and telling and demonstrating, or trying to teach. It becomes an artwork that's about exchange and, like you said, care in regard for what is needed in a certain place and time in a context.

MT: It was nice to see Pica’s friend Tobi become involved in her art project so seamlessly, too. It's such a testament to their friendship. What was the inspiration behind their friendship and making it the focal point of the movie?

CS: I still don't know how many movies you can name that are just about two women who are friends and it's not centered and fixated around a boy. Even though Pica has a crush on Malik and they are totally intimate, you never see Pica and Tobi talking about him because they're talking about their own issues. Or Pica is trying to understand why Tobi is dressed the way she's dressed. Or Tobi's just trying to hide out and find a way to stay safe from her situation. They’re focused on that. And they're focused on each other, which is a film trope that you just don't see most of the time when you see women in film. They're supposed to be fixated on men or talking about men, or one friend is like a co-writer for the other to achieve their ultimate love. Even She's Gotta Have It [1986], which is a film that I still love, [there’s] a male idea about a woman's identity in terms of her entire life being centered around being desirable to these men or desiring men. I just wanted to see a movie that was maybe contemporary, but more like Daughters of the Dust, which is about women attempting to shape their own worlds.

MT: When you were conceptualizing the film, why was it important to tell the story embedded in different cinematic genres?

CS: One of the interesting things about Hollywood cinema is genre. I like genre, but I thought of my film as something more like a Cassavetes film, which is about life. Is there a genre of cinema that's about life? People trying to live life, people just trying to take care of their families. Because Black people in America do live in a horror film. We do have friends, so we have buddy pictures. We do have love, so we have romance. All of those things are always happening at once for us. Terror and horror and fear is not separate from the mundane. It is mundane.

For me, when you're dealing with Black life, these things are not confusing. They are the actual material and environment that we live in. And maybe that's a privilege. Hollywood is an industry for whites, by whites, making product that amplifies white supremacy. That's really what it is. Part of white supremacy is about categorizing and creating hierarchies. That's the way that the creative form is also expressed. It’s things where you must stay within these lines and operate within these categories, and that makes the product easier to sell. I was never interested in that. I was interested in trying to tell stories about regular people. When Black people step out their door, they're not sure they're going to come home. And that is just a fact. And that’s not because it's a horror movie. It's because we live in a white America, a country that's always trying to kill us. And that's just also a fact. I wasn't trying to defy genre or mix genres. I was trying to depict the fabric or the actual environment in which people live.

MT: You’ve talked about how you wanted to film Drylongso on location because you wanted to foster communal participation. In what ways does that influence your style of filmmaking?

CS: I wanted to shoot on location because you have locations that are already activated, then that's a lot less work that we, as a production, have to create. Oakland I knew very well, and it was a very rich place both visually and culturally. What I learned through the process of making the film, and even much more so in retrospect, were the ways in which the community actually made that film possible through their gifts of safety, security, openness, generosity: everything from neighbors across the street letting us run power out of their house at 3 a.m. to the house that we shot [as] Pica's home, [where] we barely had any locks on the doors and $30 thousand worth of camera equipment and just me in there, sleeping alone.

And not one thing happened, not one break-in, not one incident of any incursion at all. That is because, I believe, that community decided that we were welcomed and that we should be able to do things. It was summertime, so kids didn't have school and they were bored. They would roll up on the set and notice the bagels. And I mean, if a kid asks you, “Can I have a bagel?” you don't say no. And then our crew, without any instruction, started kind of mentoring people. Kids began tagging along to work with the crew and help. Kids who were hanging out, I would have them playing in the background as extras.

Like the little girl in that scene that you mentioned. That is a neighborhood girl, we didn't cast her. She was just coming around, and we were like, “Hey, come, do you want to do this?” It was that kind of openness and generosity even in hip hop before the crazy money was there. People were doing art for the sake of art and excited about art for the sake of art. It was so much less transactional and so much more about what was possible, what we could make together. And that wasn't something that I knew going into it, but it was definitely something that made the film possible. And if the community had not been that way, the film wouldn't exist.

MT: Is that why you wanted Pica’s character to be an artist?

CS: It’s funny because the character isn't based on me, but her taking Polaroids was something that I had been doing myself with the idea of doing an art project of that kind of unformed idea. And then, in trying to think of a narrative story, I was like, Oh, that would be an interesting character because it's all about optical culture, like what you can see, images you can make, which is perfect for a film. From Antonioni's Blow Up [1966] to like Kershner’s Eyes of Laura Mars [1978], there’s so many great films where photography is central to the storytelling.

MT: I’m interested to hear about your pivot into more experimental films and art since the making of Drylongso, such as your work In the Wake [2017–ongoing].

CS: I didn't know that you could go to art school. If I had known that I probably wouldn't have gone to film school. I'm glad that I did go to film school because it gave me this particular kind of craft training that is hard to get in art school and it shapes the way I make everything now. But before I went to film school, I was learning experimental film, which is ironically separate from art, but parallel. I got excited about narrative cinema because it looked like independent cinema was going to do something to change the structure of the way movies were made and what kind of movies were made and who the movies were made about.

When I got to film school, I realized that my investment in movies wasn't the same as my classmates. Like, they just loved the idea of working in Hollywood. But I was arguing with [Hollywood] and wanted to break it. I had an argument with narrative cinema and wanted to break it. I realized that in order to do something and do it well, you have to love it. You can't be fighting with it. And I do love art. Even though it has its problems as well, they're problems that I'm interested in working through as opposed to arguing against. I think the pivot was in making Drylongso. And that my trajectory was this all along. Pica’s character in the film is the trajectory I ended up taking, even though she was completely fictitious.

Drylongso screens Thursday at BAMPFA, and Smith's short films screen Friday and Sunday. Smith will be in person for a conversation and Q&A after all three screenings.

Previously:

Drylongso screens tonight, July 5, at BAM and tomorrow, July 6, at Maysles Documentary Center in a new digital restoration.