If Raymond Depardon has been called “the French Frederick Wiseman” a few too many times, it’s because Depardon has a good mind for landing on a superficially boring yet inherently interesting subject, a good eye for what footage works, and a good heart for assembling that footage into a complicated yet emotionally poignant document. No comparison is ever perfect, but watching Depardon’s work makes one wish there were a version of this particular kind of documentarian for every country on Earth.

Like Depardon’s other rigid, almost structuralist works about the French justice system, Caught in the Acts (1994) hardly ever budges from its conceit. Over a dozen perps are brought in for routine questioning by a public prosecutor in Paris’s Palais de Justice. It’s set up as a semi-formal interview, away from the pressure of the arresting cops but without a lawyer present, where the person charged is read what they’ve been charged, given the opportunity to dispute the police record, and ultimately let go (usually for a first or minor offense) or taken away to a holding cell. There is no pathos from the ultimate sentence being read, nor is there any perverse action like arrest footage, yet each subject uses this moment, one of the worst in their lives, to spill their life stories and contextualize their crimes.

Depardon selected just a handful of the dozens of subjects he filmed to represent all kinds of cases the Palais de Justices sees: a white college kid who claims he accidentally hit a metro worker, a serial shoplifter who says she’d rather commit suicide than face prison (or stop shoplifting), an alcoholic whose first offense stabbing will be forgiven if she goes into detox, and an immigrant who will not be so easily forgiven for overstaying his visa. Some change their stories four times, others are on the verge of tears, begging for forgiveness.

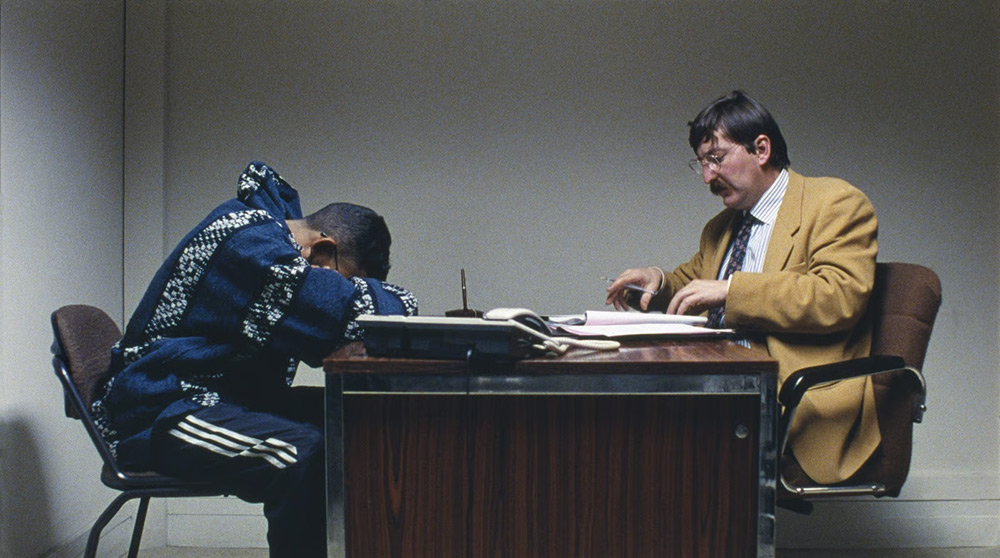

While this is ripe material for an explicitly political documentary about the inequity of the French justice system—and its subjects’ varied cases could easily support this reading—nearly every subject admits guilt to some variation of what they’ve been charged with. What interests Depardon is this unique space in which they’re given the ability to explain, in plain words, what they’ve done and how they’ve gotten to that point. Nearly every shot, save for some establishing shots and phone calls, is a two-shot with just the prosecutor and the accused in the frame. Every once in a while, if the perp stands up, a cop’s hand holding them down enters the frame, reminding us that this is not an entirely sympathetic meeting. The stars of the show are these unique glimpses into disparate French lives, so Depardon, with his training as a photographer, never distracts from that by moving the camera or otherwise prodding further.

The one exception for this strict setup is the 22-year-old HIV+ runaway, Muriel Leferle, who’s such an interesting subject for Depardon that not only is she followed past the initial interview with the prosecutor to her meeting with a lawyer and beyond, but Depardon made a whole separate film just about her story—1999’s Muriel Leferle. Yet even she, like the others, stands up at the end of her interview, her head now above Depardon’s strict frame as she walks out, her fate undetermined.

Caught in the Acts screens tonight, February 21, and on March 1, at Film at Lincoln Center as part of the series “Raymond Depardon: Humanity in Focus.”