Tom Schiller spent 11 seasons as a writer on Saturday Night Live. During this time, he wrote and directed a series of short films that took direct inspiration from European arthouse cinema and classic Hollywood films. They include such titles as Don’t Look Back In Anger, Java Junkie, and Perchance to Dream. Often shot in black-and-white, delicately assembled, and involving surreal, noir-ish plots, these shorts (now collected as “Schiller’s Reel”) epitomize the strange singularity of his directorial sensibilities. In fact, all three of the aforementioned films were shot in black-and-white and, in retrospect, feel like complete oddities—then, and certainly now—when considered as part of SNL’s program; it’s almost as if the joke is that his films don’t fit in with the rest of the show.

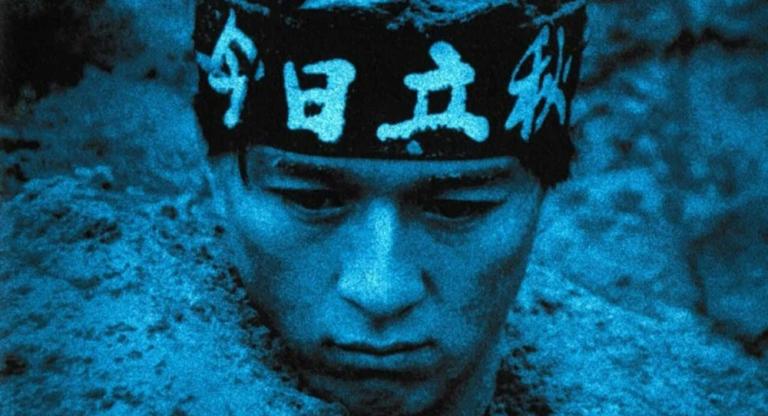

While I believe the exceptional quality of these shorts reflects the genius of Schiller’s wit and whimsy, it is impossible to discuss the comedian’s work without bringing up the status of his still-unreleased feature film debut, 1984’s Nothing Lasts Forever (pictured at top). Set in New York amid a hundred-day strike that’s forced the personnel at Port Authority to take control of the city, Schiller’s film offers a zany spin on your typical bildungsroman, tracing the ups-and-downs of wannabe artist Adam Beckett (Zach Galligan, of Gremlins fame). It’s a film of polarities: of an artist’s mania and melancholy; of tunnels beneath Carnegie Hall and a shopping center on the Moon; and, of an encounter between actors from different generations, with Schiller casting such talent as Sam Jaffe and Eddie Fisher alongside then-newcomers like Bill Murray and Dan Aykroyd. Though the film was never released—perhaps because it was too odd, or perhaps due to issues regarding its archival material—it has become a cult film and earned the praise of critics like Richard Brody, among others.

Ahead of tomorrow’s celebration of Schiller’s career at the Roxy, I managed to speak with him over the phone to discuss his love of François Truffaut and Federico Fellini, how he got involved in Saturday Night Live, the production of Nothing Lasts Forever, and his newfound acting career. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer: I understand your father worked on I Love Lucy while you were growing up. Did your proximity to the world of television when you were a kid inform your practice later on?

Tom Schiller: Yes. It gave me an early glimpse of television production, of how things worked. When I was around nine or ten years old, I got to go to the filming of I Love Lucy. As a kid, it was fascinating to watch. I used to sit in the sound booth with the technician, who showed me the moving VU meters. Right below, I could see the huge Mitchell cameras on dollies, moving in-and-out to get wide-shots and close-ups. There was one time I went there and Milton Berle was on the show. He showed me the three-headed Moviola, which was in synchronization with all the three cameras.

NP: After that, you worked on documentary films about Buckminster Fuller and Henry Miller. How’d that come to be?

TS: I grew up in the Palisades. Sadly, it’s half missing right now. But anyhow, I met this guy named Robert Snyder who had just won an Academy Award for a film called The Titan: Story of Michelangelo [1950], which he’d co-produced with this guy named Robert Flaherty who was supposedly the father of documentary film. So I got to be an apprentice to a really established documentary filmmaker and we made films about Bucky Fuller, Anaïs Nin, William de Kooning, and Henry Miller, who I became friends with.

NP: How did you first meet Snyder?

TS: My friend was one of the Whitney Brothers—they used to make abstract motion pictures in the ‘40s. They were avant-garde. He had worked for Snyder as a sound-man, so I met Snyder and asked him if I could be his apprentice. They had this thing in high school where I’d do half-a-day at school and half-a-day working with him.

NP: Throughout your work, there are direct references to arthouse cinema and foreign films. When did you first encounter the work of filmmakers such as Fellini and Truffaut—was it during this time-period or later on in your life?

TS: It was around this same time. In Los Angeles, there were only about two or three art-houses. I’d go watch these marvelous films by Fellini, Truffaut, and people like that. I fell in love with them. At that time, after seeing Truffaut’s The 400 Blows [1959], I decided I wanted to become a foreign film director.

Once, I saw a Fellini film and was totally blown away. I was driving back home and ran a red light. A cop stopped me and said, “Why’d you do that?” I said, “I just saw a Fellini movie.” He let me off.

NP: Do you remember which film of his it was?

TS: It was either 8 ½ [1963] or La Dolce Vita [1960], which remains in my pantheon of the best films ever made in the whole world.

NP: After that, you ended up moving to New York and working on SNL, but I’m curious what happened in the interim?

TS: As I said, my dad worked on I Love Lucy and every sitcom after that, including Maude, with his partner Bob Weiskopf. When he was writing on a show called The Beautiful Phyllis Diller Show, which is a credit he didn’t brag about too much, he said to me, “You should meet this guy, he’s a Canadian and he knows every good restaurant in LA.” I thought, “I don’t care about every good restaurant in LA, but I’ll meet him anyway.” So one day, I was up at my dad’s house and he brought over Lorne Michaels and his friend John Head.

Lorne seemed like a nice guy. We hung out a little bit, smoked a joint, and I became buddies with him. I used to hang out with him at the Chateau Marmont. There were a lot of people who ended up working on Saturday Night Live living there at the time. He kept saying, “Come work on this new show I’m going to start! It’ll be a late night comedy.”

Now, I didn’t want to work on a late night comedy show because I wanted to be a foreign film director, but he was persuasive and he kept talking about this show over and over and over again. He was just obsessed with it. Finally, I realized, I’m not going to become a foreign film director in Los Angeles. New York is closer to Europe and I said, “Yes.” At first, it was just the two of us in a tiny office at 30 Rockefeller Plaza. That was the whole show.

NP: In a way, you did manage to make films that shared the same aesthetic sensibilities as those made by the European directors you admired during your time at SNL. A lot of the shorts that make up “Schiller’s Reel” are completely unlike most of the short films that were produced for the show—they’re often in black-and-white, shot with canted angles, and prone to the surreal. How did you develop this unique visual style?

TS: I admired foreign films from the ‘60s, which were black-and-white and surrealistic. I wanted to emulate that feeling and I had a slot at Saturday Night Live, which was a live, color, video television show. I knew that a black-and-white film would stand out a little more, so I kept doing mine in black-and-white.

NP: Indeed, there’s something inherently subversive about the use of black-and-white in this context. Plus, there are other recurring motifs in your shorts from SNL that connote a sense of authorship. I’m particularly curious about the recurrence of coffee and sushi in these films. Could you speak to this and other recurring markers in your work?

TS: Well, I like coffee and I like sushi. It’s nothing more or less than that. They make compelling subjects. Lost Weekend was about alcohol. Java Junkie was about coffee. For the other ones, I was just emulating my heroes, like Fellini and Truffaut. A lot of the shorts were salutes to them.

NP: There’s also a more dramatic component to these shorts, as seen in Bill Murray’s performance in Perchance to Dream and John Belushi’s in Don’t Look Back in Anger. How’d you get away with this on SNL?

TS: Well, there’s that old trope that every comedian really wants to do drama. I got to know these people so well—Belushi, Bill Murray, Chris Farley—that I got to see their souls. I thought, if I can really capitalize on what’s inside them, that’d be great. They enjoyed not having to do laugh lines every two seconds.

NP: With time, we’ve seen Bill Murray become a sought-after dramatic actor. What was it like being in the company of these famous comedians right before they became celebrities?

TS: It's a very interesting period in an actor or comedian's life. For example, I knew Bill was going to be huge. When we hung out around town together and nobody knew who he was, I’d say, “These are the final days of anonymity.” And they were. Within the year, he had become a major star.

Belushi… You see these people interact with other people and you see their true character. It was fascinating to watch them change. To be a fly on the wall and observe how people related to them once they became huge celebrities. I could capitalize on that by catching them on the way up. I was lucky.

NP: I think this marks a fitting moment to talk about Nothing Lasts Forever. How did that script get started in the first place?

TS: After the first five years of Saturday Night Live, Lorne somehow got a deal with M-G-M to make five movies. Five of us, including myself, were asked to write scripts. I was just told to do a “Tom Schiller movie.” I was delighted, because that’s all I wanted to do in the first place. So, I wrote Nothing Lasts Forever. It took me about three months. And out of all of the scripts that were written, they chose mine to put into production. I still don’t know why. It wasn’t like Animal House [1978]. It was a weird movie about a bus to the moon. I lucked out.

NP: It’s more than just about a bus to the moon. It has this wonderful satire of New York’s Downtown arts scene and a very relatable main character. And, it’s constantly referring back to noir films and 1950s sci-fi flicks. What was the genesis of the film’s story?

TS: I couldn't say. I just took some yellow pads, went outside, sat down at cafés, and started writing. This is just what came out. I knew that I wanted to make fun of the art world—which I did, a little bit—and show how old people are shunted aside in our society. And, I wanted to touch on consumerism, which is a timely thing right now. It’s become so overblown. People are getting bad deals and think they have to shop all the time. But, I really couldn’t say. This all just came out of my unconscious.

NP: There’s a great deal of specificity in the world you create, specifically in your vision of the art world. What was your relationship to the gallery scene of the time?

TS: I’ve always been around the art world. A lot of it is magnificent stuff that I admire and I don’t make fun of. But a lot of it is fake. To me, a man on a treadmill is pretty much the epitome of a fake art thing.

NP: It’s a futile gesture. But, what I’m curious about is the fact that there were several artists and filmmakers involved in the art scene at that time who also displayed an interest in a previous era of cinema that seemed irrecoverable in the ‘80s. Figures like Alyce Wittenstein and Andrew Horn, for example. Did you have any relationship to these artists, and did their work influence Nothing Lasts Forever?

TS: They did and they didn’t. I didn’t know them that well, but I certainly admired those avant-garde people. When I was 16 in Los Angeles, there was a movie theater called the Cinema Theatre and they used to have something called “Movies Around Midnight.” They showed really experimental, New York movies. Work by the Kuchar Brothers and Ed Emshwiller. I always loved the work made by those people. Those were the kinds of movies I used to make with my friends when I was 16 and 17 years old. So, they did have an influence on me.

NP: I’d like to return to the production and circulation of Nothing Lasts Forever. I read that after you finished the film, it was invited to the Cannes Film Festival twice but M-G-M prevented it from going.

TS: Well, I had just finished editing the film and I’d heard that there was this fellow named Pierre-Henri Deleau from Cannes who was in New York looking for films that could be shown in the Director’s Fortnight. I snuck a print down to him and he called me back and said, “You have created a chef d’oœuvre!” A masterpiece. I was brimming with excitement. He then said, “Come to the Algonquin.” In the lobby, he gave me a glass of champagne and said, “You will be the talk of the festival. We want your film.” I was bubbling with excitement, because that’s all I wanted to do: to be a French film director.

I told the president of M-G-M, a guy by the name of Freddie Fields. At the time, M-G-M was struggling. He said, “You can’t go to Cannes.” And I said, “Why not?” Then he said, “You can get hurt at Cannes.” So I said, “Give me the name of one film that was hurt at Cannes.” And he said, “Baby, I can have a list of 50 on your desk by tomorrow.” He never gave me the list and I never went to Cannes.

NP: What prevented the film from being released in the U.S.?

TS: This is the mystery of my life. I have no real idea. I can guess that some of the footage wasn’t released, or the music, or something like that. But, to this day, I really don’t know. It became a cult film, which I’m happy about.

NP: I imagine there have been efforts to release it on physical media, or rescue the film in some way or another. Have you followed these efforts?

TS: There have been many inquiries about showing it or putting it out on DVD, but everything is thwarted by Warner Brothers, which now owns it and has buried it.

NP: After Nothing Lasts Forever, I’m assuming you returned to SNL?

TS: That’s right, I went back for another six years and made more films. But then I was let go along with other writers, so I was out of work and I chose to pursue advertising as my next step.

NP: You seem to have anticipated this move in your own work at SNL with the Hidden Camera bit you did with Farley.

TS: Yes, that’s a funny thing. I guess I prefigured this move by doing fake commercials first and then real ones later. The other thing is that when they go to the moon on the bus [in Nothing Lasts Forever] they’re forced to go shopping. But then I ended up making commercials, making old people go shopping. I ended up becoming what I made fun of.

NP: You’ve also become an actor in more recent years.

TS: Yes, I was very lucky to meet Conor [Dooley] and Eric [Paschal Johnson], who wrote and directed Observatory Blues [2017]. Conor was a Marine; therefore, a very disciplined director. Eric is a minister from the Berkshires, and a very spiritual man. Anyhow, they asked me to be in this film about a hand-less writer of erotic fiction. Who could pass up a role like that?

I was very lucky to work with them. They’re creative and smart. The film was absurd, but it also had a touch of humanity and nostalgia.

NP: Yes, the short manages to balance comedy with something a touch more emotional in a really effective way. I was quite moved by it. What’s kept you busy in more recent years?

TS: I've kind of reached my Salinger years, which is sort of to be quiet and live in the country, and watch my favorite TV shows, which are on TCM. I like to watch old black-and-white movies from the ‘30s and ‘40s. I adore them and can see them all the time on TCM. When I’m not watching them, I watch my other favorite television show: America’s Funniest Home Videos.

“An Evening with Tom Schiller” will take place tomorrow, December 6, at the Roxy. Director Tom Schiller will be in attendance for a Q&A moderated by Conor Dooley and Eric Paschal Johnson.

Special thanks to Kendra Mosenson and Milo Straghalis for making this conversation possible.