As I write this, the New York Times has just published an article on how the White House will not recognize World AIDS Day for the first time since 1988. The State Department is requiring that White House staff "refrain from publicly promoting" the day "through any communication channels, including social media, media engagements, speeches or other public-facing messaging." When our government demands its employees omit their awareness of a disease that has historically swept tragedy across our culture and people, where do we turn to hear about it now? If somebody dies of AIDS or AIDS-related complications, but nobody around is going to tell you about it, does that mean AIDS is no longer happening? Silence is a form of omission, but when coming from a government it's a short hop to censorship.

From 1983-1986, the artist Niki de Saint Phalle wrote and illustrated the book AIDS: You Can't Catch It Holding Hands (1986), which explains how the disease is transmitted and humanizes its victims. Written with the help of AIDS specialist Dr. Silvio Barandun as a letter to Saint Phalle's son, Philip, who later adapted the book into animated PSAs in 1990 with music by David Byrne, the films are unable to be found online today, circulating instead through limited-run museum shows. They will screen, however, at Anthology Film Archives in the program "PSAs: Economy/War/Health" as part of the longer series, "Avant-Garde Ads: Part 1." As our government revokes arts funding and shields important information from the public, "Avant-Garde Ads" offers an important look at how the media has sought to manipulate consumers, and how artists have in turn sought to manipulate the media (sometimes even getting paid to do it).

Spread across 13 themed programs, the 130+ works in this first part of Anthology's "Avant-Garde Ads" include 19 titles on 16mm and 10 on 35mm, some of which are less than a minute long (tipping my hat to you, projectionists). This smorgasbord of films and videos showcase a small but varied sampling of what constituted content before we relied on the ephemerality of targeted social media scrolling and click-bait headlines.

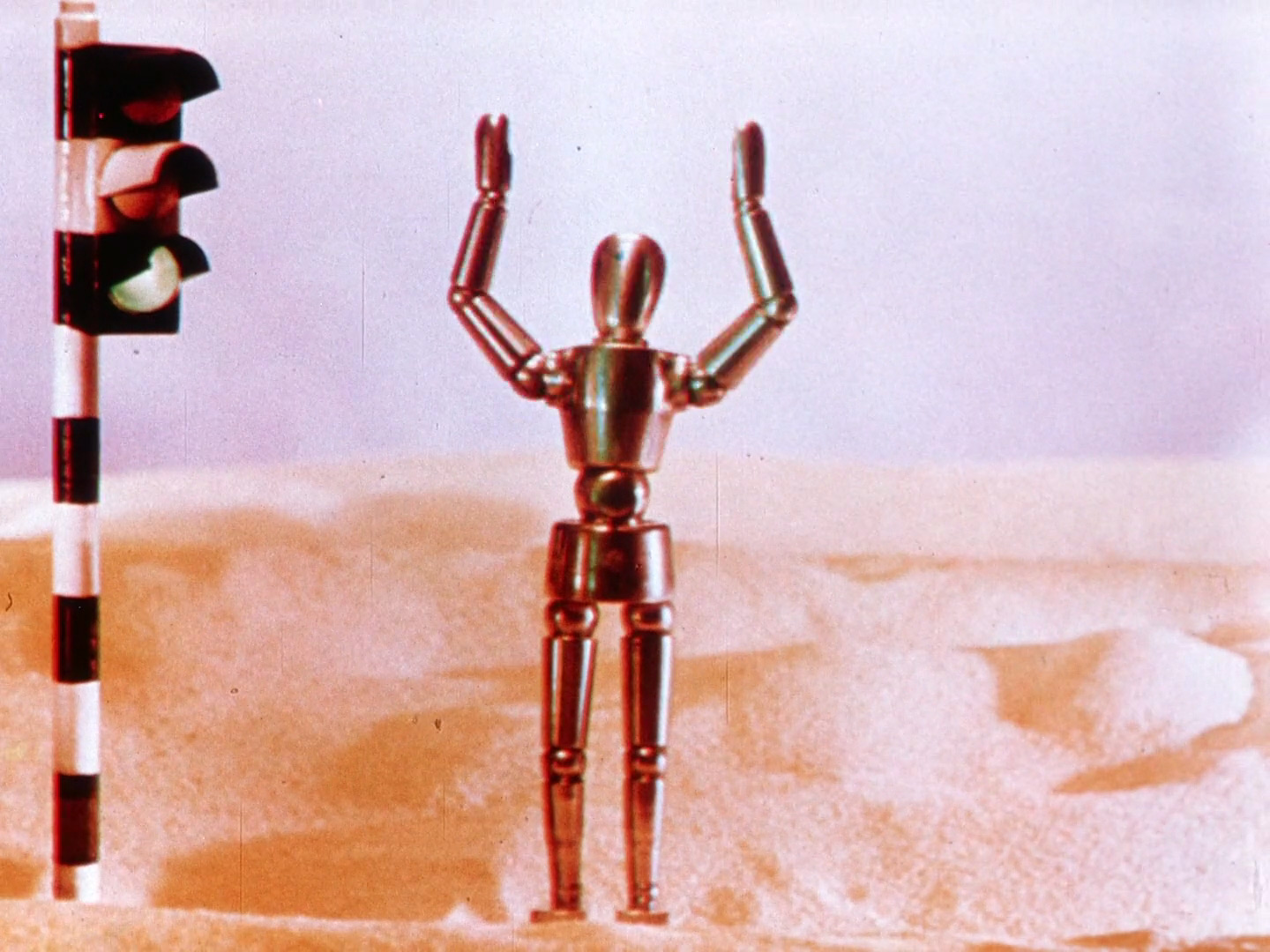

The 18-film program "Advertisements (1920s-40s)" kicked off the series, setting the foundation for how marketing would appear on screen over decades. Postcards, periodicals, and newspapers were the norm when it came to advertising before moving images. But with film, the use of time became a new luxury for marketing. Whole stories could be told, uses explained, and claims proven before audiences’ very eyes. Six years before he worked with Maya Deren on Meshes of the Afternoon, Alexander Hammid crafted a narrative that combined all of these aspects in his 4-minute ad for Bata tires titled "The Highway Sings" (1937), co-directed with Elmar Klos. Other early ads in the program focus on film itself. Two of these were directed by Len Lye (who has films in multiple programs) and will screen on 35mm. There’s his colorful and upbeat ad for Churchman Cigarettes, "Kaleidoscope" (1935), and his longer foray into animation's possibilities in "The Birth of a Robot" (1935), which features changing perspectives, timelapse effects, colorful graphics over live-action puppets, and even a good "witch" and metal man in need of some oil—here provided by Shell, who funded the ad—years before color dazzled The Wizard of Oz (1939).

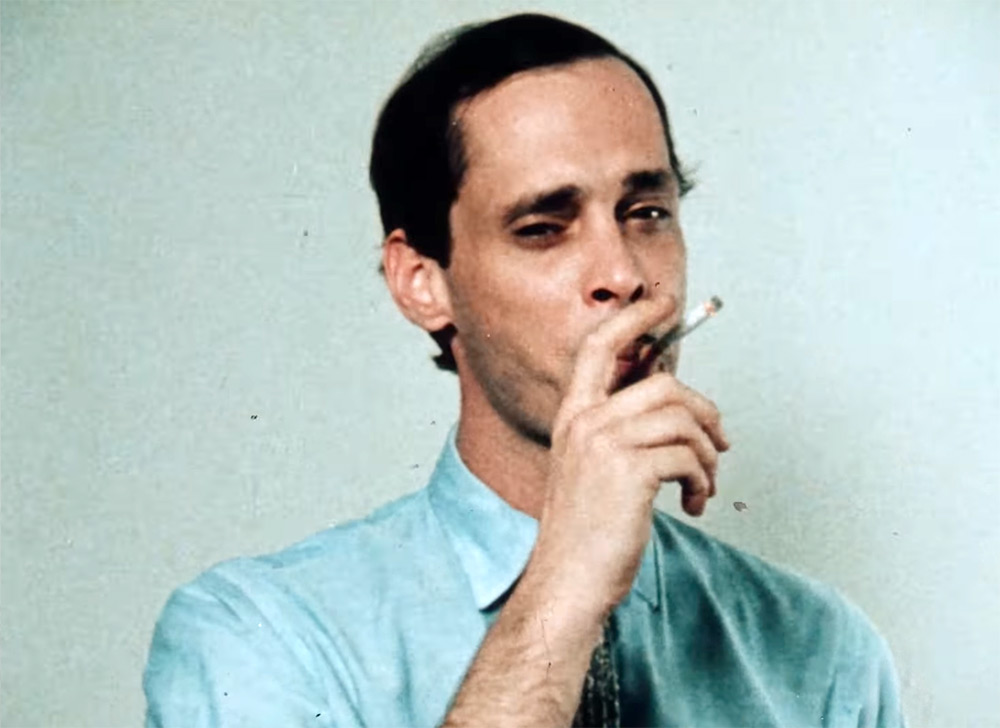

Spanning a much denser period of media, the mammoth program "Advertisements (1950s-90s)" includes 39 works by filmmakers known for experimental shorts (Jordan Belson, Peter Kubelka, Pat O'Neill, Dara Birnbaum, among others) and directors recognized for arthouse films (Ingmar Bergman, Paul Bartel, David Cronenberg, and more). In 1982, Landmark's Nuart Theatre in Los Angeles commissioned a "No Smoking" spot from John Waters and Douglas Brian Martin. It features Waters complaining about being told not to smoke and taunting the audience. Although he's endorsing the legal ban on smoking inside a cinema, Waters doesn't let the commission stop him from sharing how he really feels: "I'm supposed to announce there's no smoking in this theatre, which I think is one of the most ridiculous things I've ever heard of in my life. How can anyone sit through a length of a film, and especially a European film, and not have a cigarette?" After a teasingly delectable drag on his cigarette, he adds, "Smoke anyway. It gives ushers jobs, and if people didn't smoke, there'd be no employment for the youth of today." Waters was commissioned because he's John Waters, the "People's Pervert," and if he wasn't himself in this ad, then what would be the point of having him do it? (More recently, Waters, who is now in his late 70s, admitted he regrets becoming a smoker.) This 40-second bit will be screening on 35mm, as intended.

The late David Lynch is well remembered with seven different ads from 1991 to 2011 (plus one in another program), each tapping into the same surreal unknowns that permeate his longer works, with nods to Eraserhead (1977) and Twin Peaks (1990-1991), especially in his campaign for Georgia Coffee. For the Japanese canned coffee product, Lynch directed a micro-arc of short, faux Twin Peaks episodes exclusively aired in Japan that starred several of the show's cast members and always end with Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) cracking open a can of Georgia brew with Ken (Taka Haguchi, in one of his earliest roles), a man searching for his Laura Palmer–style missing wife. Lynch's 4-minute commercial for David Lynch Coffee (2011) has him voicing both sides of a conversation with Barbie, who eventually asks him if the coffee is good ("Yeah, it's really good," Lynch answers), organic ("Yeah, it's organic!"), and fair trade ("Yeah!"). Barbie throws in that she thinks he's "kinda cute," and it's hard to disagree. Mattel supposedly did not approve of the video.

Two separate programs focus on social messaging. "Culture + Education" will show 5 prints on 16mm, including Jonas Mekas's "Film Magazine of the Arts" (1963), commissioned by Show magazine. When they told Mekas they wanted something unusual, after he had protested that his own work was surely too unusual for them, he turned in a film that travels around New York happenings, museums, theater rehearsals, costume ateliers, and more. Show rejected it because the magazine was never part of the 20 minutes of footage. In Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler's "Library" (1970), a charmingly clever marketing campaign for the Sussex County library system of New Jersey, townspeople and the various books they consult to help them with their work and hobbies are featured with a score by Tony Conrad, and narrated (in a monotonous drawl that does a disservice to the otherwise informative and endearing film) by Conrad's then-wife, Beverly, known primarily now only as Beverly Grant. Before narrating "Library" (one of her last film appearances), Grant had been in films by Mekas, Gregory Markopoulos, Andy Warhol, Ron Rice, Jack Smith, and Stephen Dwoskin.

"Culture + Tourism" includes several works by Len Lye and two longer-form pieces, the collaboratively made "Pittsburgh" (1959) and Hans Richter's "The New Apartment" (1930). The latter, a commission for the design group Schweizerischer Werkbund, sees Richter use various stylistic devices to emphasize the uselessness of ornate furnishings in old buildings; in turn, producing an argument in favor of the efficient and utilitarian buildings of the future his commissioning body wishes to build. It's a silent piece of design propaganda made up of surprisingly beautiful shots, even if its proposed future ends up looking like a grim cell block of cookie-cutter cubes called housing.

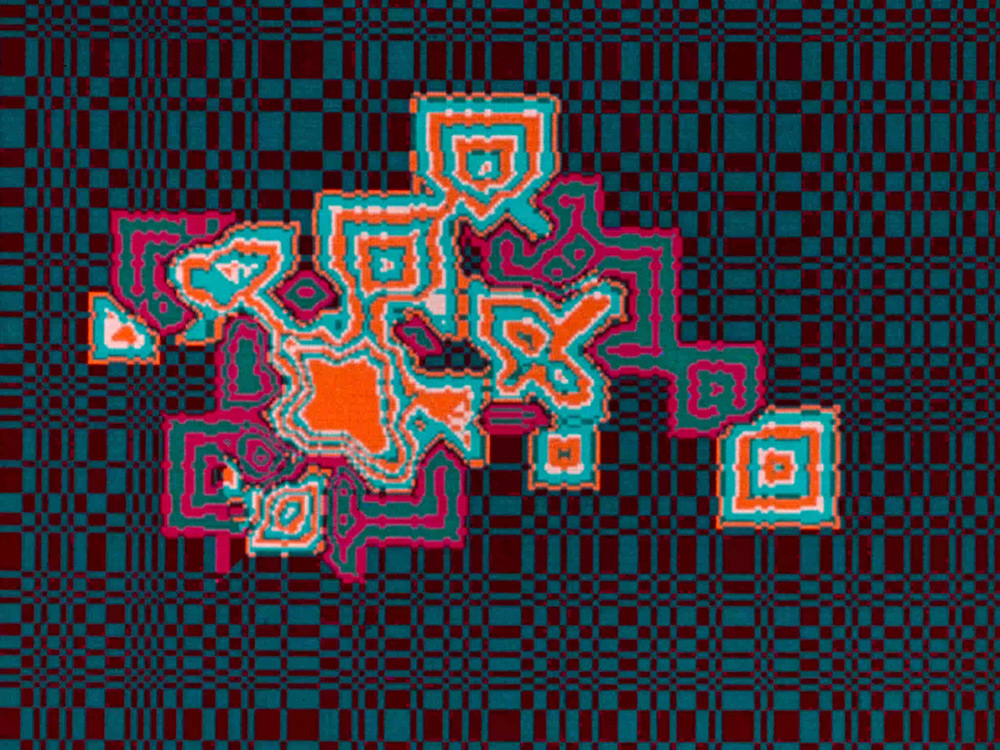

The category "Industrials/Communications" is split as well, with one program focusing on "Radio" and the other on "Technology + Mathematics." The former includes six works from different directors for Philips Radio and two for Telefunken, all made between 1931 and 1962. The latter largely deals with computation, and includes works like John Whitney, Sr.'s technical "Experiments in Motion Graphics" (1968), which screens on 16mm. Three of the strobing computer pieces Lillian Schwartz created at Bell Labs between 1970 and 1972 will also receive a theatrical screening. "Pixillation" (1970) was Schwartz's first moving image work, created in collaboration with Ken Knowlton, who is debatably credited with having invented the pixel. Since Schwartz was not adept at computers, Knowlton built her the EXPLOR language: Explicit Patterns, Local Operations, and Randomness, which becomes self-explanatory in her pieces. Schwartz, who did not have a solo show until age 89 in 2016, had been involved with the artist-engineer collective Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) before working at Bell Labs from 1968-2002. Only in 1984 did she begin to receive a salary and contract from Bell—she had been a "Resident Visitor" who simply continued to show up at the New Jersey campus for 16 unpaid years. MoMA commissioned her to make a 30-second digital ad for their 1984 renovation, which won Schwartz an Emmy. Unfortunately, that ad is not screening in this program.

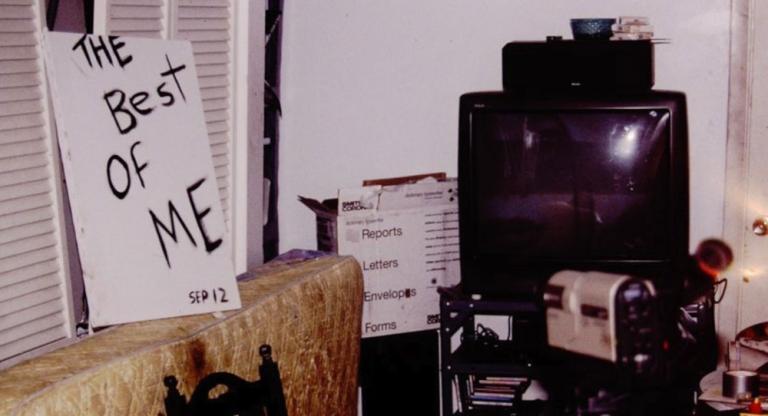

"Artist Ads" showcases 14 works generally recognized as video artworks. For example, Richard Serra and Carlota Schoolman's "Television Delivers People" (1973), which is a staple critique of media power and consumer submission. In contrast, Tony Cokes modifies the typographic forms of letters in the text for well-known taglines in "Ad Vice" (1999). Placing themselves into the role of subject is another way artists can deliver their own critiques: Lynn Hershman Leeson, Chris Burden, Michael Smith, and Ilana Harris-Babou are a few of the self-referencing directors here, while Joan Logue collaborated with various "New York Artists" to shoot their 30-second portraits. "Ads as Found Footage, Pgm 1" continues to look at the artist's view of advertising with Andrew Lampert's "Benetton" (2004), an ongoing remix of discarded 16mm fashion campaign footage, and Harun Farocki's 44-minute "A Day in the Life of a Consumer" (1993), which cuts together decades of German television ads to form a monoculture day, from wake-up to work to bedtime. Farocki's documentary argument that commercial studio photography is rooted in 17th century Flemish painting, "Still Life" (1997), screens with two other titles in his own program, "Harun Farocki on Advertising."

Anthology Film Archives was opened in 1970 by a group of artists that included Jonas Mekas, Peter Kubelka, and Stan Brakhage, all of whom are featured across this series (see the Brakhage-only program). While many of the other programmed filmmakers circled in and around each other in New York's avant-garde art and cinephile scenes, fresh Anthology blood is also in the mix. Projectionist Rachael Guma's "Extra Ultra Super Gal" (2024) is a short, crafty stop-motion short that advocates for better menstrual products and advice for women with heavy periods. Screening in "PSAs: Economy/War/Health," Anthology staff and related filmmakers voice the anthropomorphic tampon, menstrual cup, and other feminine hygiene products.

Avant-Garde Ads: Part 1 runs until December 16 at Anthology Film Archives.