All of director Raoul Peck’s films—from the late 1980s onwards—have been about different forms of colonialism around the world, but he remains rooted in his native Haiti. His two first narrative features, Haitian Corner (1988) and Man on the Shore (1993), take place there, and he has said that his Third World consciousness would prevent him from ever making a film that he would be ashamed to show in Haiti. “[We] are not free. We are bound,” he once told an interviewer, declaring that our own families and peoples must be the ground from which we set out to explore the struggles of others.

This is what James Baldwin, the principal subject of Peck’s ambitious new documentary I Am Not Your Negro (2016), did in No Name in the Street (1972), in which reflections on his youth in Harlem and his experiences in the Civil Rights movement provide the backdrop for an investigation of the status of Algerians in France (among other things). From Haiti, Peck turned his attention to the Congo with the biopic Lumumba (2000) about the rise and assassination of the charismatic decolonization leader. Comparisons (perhaps superficial) to Spike Lee’s Malcolm X (1992) indicate another affinity between Peck and Baldwin, who was hired in 1968 to write a treatment of Malcolm’s Autobiography (it was supposed to star Billy Dee Williams, who once played Martin Luther King Jr. on stage), which, heavily edited by Arnold Perl and sold to Warner Brothers, languished for decades until Lee unearthed it. In Sometimes in April (2005) Peck depicted the Rwandan civil war of 1994, then in Moloch Tropical (2009) and Murder in Pacot (2014)—his most recent fiction features if you don’t count the yet-to-be-released The Young Marx (2016)—he returned to the theme of Haiti.

I Am Not Your Negro director Raoul Peck

Several reviews of I Am Not Your Negro have drawn the conclusion that history repeats itself. A thorough scrutiny of this phrase deserves an essay of its own (it appears to have been coined by George Eliot in 1858, possibly as a paraphrase of Marx), but suffice it here to observe that it indicates a lazy view of history, whose trends and long waves are too complex to be shrugged off with such a truism. It is said that we (who is this ‘we’—humanity in general?) allow this repetition to happen by being so thoroughly ignorant of our past mistakes. The apparent humility of this notion masks its smugness, because what is usually meant by ‘we’ is ‘the uneducated among us’—in other words, that old scapegoat, the idle poor. When Baldwin allows himself to echo this notion, he has a different group in mind: “[T]hough no one appears to learn very much from history, the rulers of empires assuredly learn the least. This unhappy failing will prove to be especially aggravated in the case of the American rulers, who have never heard of history and who have never read it”. Instead of being blinded by their lack of educational opportunities, they’re blinded by their power, by the half-conscious suppression of part of their humanity that protecting their positions necessitates.

The film’s contemporary relevance is its most consistently cited attribute, from “as crucial and relevant as ever” to “so relevant, it’s terrifying.” Variety’s Owen Gleiberman goes as far as to claim Baldwin as a prophetic thinker who speaks from a past that has finally caught up with us, like the “untimely” Nietzsche, whose diagnosis of Western civilization’s terminal nihilism is becoming more and more undeniably accurate. Baldwin’s tone can reach apocalyptic heights too, as it does in the epilogue of No Name in the Street, where he proclaims that “the Western party is over and the white man’s sun has set. Period.” Having been an Evangelical preacher in his teenage years, it’s perhaps not surprising that he would have this gift of fire-and-brimstone oratory.

Baldwin’s composure, erudition, and passion as a public speaker are prominent in I Am Not Your Negro , with clips from a 1968 episode of The Dick Cavett Show , a 1963 episode of Florida Forum , a 1965 debate at Cambridge, and more. A voiceover narration—composed of texts ranging from The Devil Finds Work and No Name in the Street to the unfinished 30-page manuscript Remember This House —is delivered by Samuel L. Jackson with what The Village Voice ’s Odie Henderson described as “an almost feminine quality,” in extreme counterpoint to what Cinema Scope ’s Steve Macfarlane called “the Snakes on a Plane voice he uses to pay his kids’ college tuition.” Baldwin himself spoke with a sophisticated, cosmopolitan accent, which he called “Northern” and often had to keep to himself in hostile surroundings in the Deep South. His insecurities as an outsider (a foreigner in Paris, an East Coaster in Hollywood, a Northerner in Montgomery) are articulated in his account of a 1967 meeting with Eldridge Cleaver, who Baldwin assumed considered him “a dangerously odd, badly twisted, and fragile reed, of too much use to the Establishment to be trusted by blacks.”

Crowd gathering at the Lincoln Memorial for the March on Washington in I Am Not Your Negro. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

Baldwin, like many of the engagé celebrities in whose circles he moved (among them Sammy Davis Jr. , Eartha Kitt , Marlon Brando , Harry Belafonte , and Lorraine Hansberry ), was torn about how to relate to “the people.” Artists, he wrote, “stand forever at an odd and rather uncomfortable angle” to the people they “hope to serve.” Raoul Peck, who shares Baldwin’s commitment to his people, was similarly detached from their struggles by his privileged background (educated partly in the United States and France and having studied at the German Film and Television Academy in Berlin under filmmakers like Alexander Kluge and Krzysztof Kieslowski). He admits that after spending a lot of time on the international festival circuit, he can sometimes “start to forget that people are dying in my country,” a problem not limited to Peck’s filmmaking practice but common to any branch of the culture industry with pretensions to social responsibility. The question is, is it possible to combine the kind of historical analysis that can actually expose the roots of our societies’ sins with mass popular appeal? With Sometimes in April , produced and distributed by HBO Films and starring Idris Elba, Peck flirted with mainstream exposure. When its run at Film Forum starts on February 3, I Am Not Your Negro will also be opening at the AMC Magic Johnson in Harlem, hopefully expanding its audiences beyond the handful of middle-class white liberals that would have seen it at festivals. With nods from Vibe and BET, a boost from Samuel L. Jackson’s fame, and its Oscar nomination, maybe its profile already exceeds that of standard arthouse fare.

The relevance of I Am Not Your Negro will not be purely on the strength of Baldwin’s discourse—prophetic as it is—that the film will move its audience, but also by the direct way that it implicates us in this country’s sordid history of slavery, police power, and racial bitterness, which no one can honestly claim we’ve gone to any significant lengths in atoning for. Atonement and forgiveness are, moreover, misleading concepts in this context, since they imply that the crimes thus related to are accomplished facts, whereas the systematized mass-murder of populations deemed superfluous by the economy and the law is an ongoing process. The riot cops beating civil rights demonstrators in 1960s archival footage look affable compared to the militarized death squads attacking the residents of Ferguson and St. Louis over the past few years. By putting footage from then and now side by side, Peck makes it very clear that police violence is only getting more brutal, that government at every level—federal, county, and city—is only tightening its grip around the people it pretends to represent.

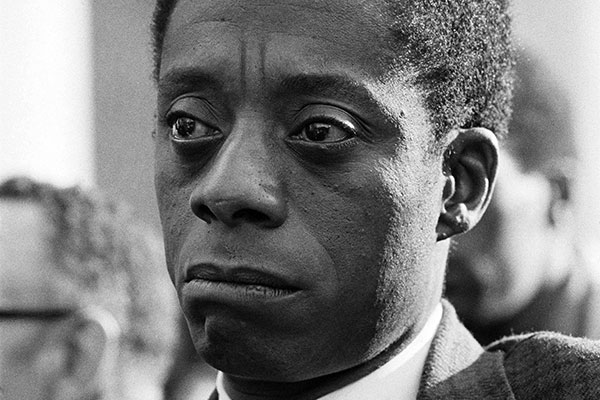

James Baldwin in I Am Not Your Negro. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures. Photo Credit: © Bob Adelman, all rights reserved