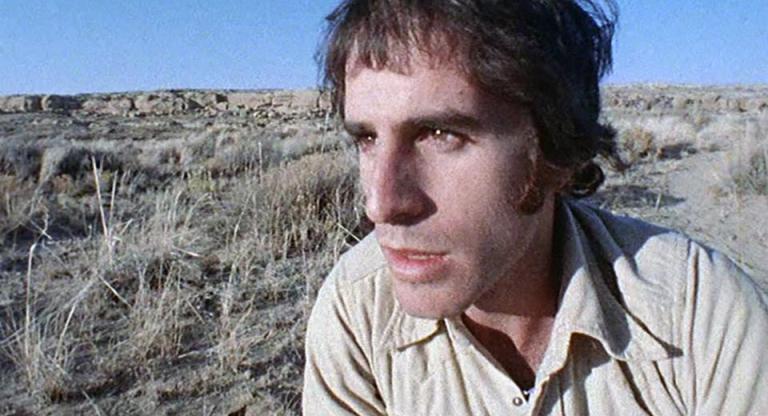

Feeling nostalgic for earlier forms of nostalgia sounds like some meta-Proustian hell, and perhaps it is, but that’s not the fault of Doc’s Kingdom (1987) so much as the changing world around it. When Robert Kramer shot it in Portugal, it had the heavy, somber air of a funeral dirge for the failed promises of the Long Sixties: New Lefts, anticolonial revolutions, and liberation movements whose clarion call of a luta continua—“the struggle continues”—could not contend with the forces of capital that had constricted around the throat of the global left by the 1980s. This leaves Doc, the exiled American physician played by Paul McIsaac, washed up “somewhere on the frontier of Europe, it doesn’t really matter,” after burning himself out with drink and disease in 1970s Africa. When his abandoned son Jimmy, played by a young Vincent Gallo, suddenly shows up, it sparks a long dark night of the soul.

To watch Doc’s Kingdom today is to revisit a time when the broader left may have collapsed but the postwar liberal order, for all its imperialism and extraction, had at least not yet regressed to our Fortress Tech-Bro fascist hellscapes, when Donald J. Trump was just a “short-fingered vulgarian” mocked in Spy magazine, not the mad king of bad-math tariffs. In 2025, we can but long for the left-melancholia of 1987.

Doc’s Kingdom is certainly auteur cinema from the premier radical filmmaker of the U.S. New Left, a worthy but overlooked successor to Kramer’s earlier autopsy of the white left in Milestones (1975). But Paul McIsaac crucially animated a key Kramer trilogy: as Jim, lead armed insurrectionist in Kramer’s incendiary Ice (1970); then again, as Doc in Route One/USA (1989), the four-hour docu-fiction survey of the late Reagan years. We spoke about Doc’s Kingdom, politics, and McIsaac’s eclectic screen career, mostly a side gig to his many years as a radio journalist at WBAI and NPR, but with some notable turns.

Whitney Strub: For readers not already steeped in your collaborations with Kramer, can you clarify: is Doc the same character you played in Ice and then Route One/USA?

Paul McIsaac: Well, it turns out to be that neither of us had any notion of that in the beginning. The revolutionary who is standing in the phone booth at the end of Ice—there was no plan that that character would still be alive. We didn’t stay in touch after that. It was only all those years later that we met up again after he'd been in Portugal, and was then in France and making completely different films. I had spent my time as a journalist on the road, meeting people. I did a radio piece on the Free Vermont commune movement that Robert had participated in. That reconnected us.

What he was carrying at that time was his relationship to his father, who was a doctor [Milton Lurie Kramer, who passed away in 1965]. I don't know if you know his history at all, but he was one of the first doctors who went to Hiroshima. Robert had felt alienated from him, but also respect, so he wanted to explore the doctor. He was reading John Berger’s A Fortunate Man: The Story of a Country Doctor [1967], and as we began working together we also drew on Alan Berkman, who was in many ways Doc. He was a doctor, he went underground. He took the direction of Ice that neither Robert nor I took. He became a pistolero; he was actually underground, sticking up supermarkets for money. With great regret, later he realized he was part of a cult and so forth, and went on to do extraordinary work in AIDS public health work while incarcerated.

I brought Alan to Robert, and said that maybe there's some connection here. And that's how the character in Ice enters Doc’s Kingdom, through that interaction, that dialectic of our working together. It was never a plan from the beginning, it was a trilogy created in retrospect.

WS: Doc is this fascinating synthesis of Kramer’s different eras. First, there’s you, Newsreel member Roz Payne, and cameraman Robert Machover, who shot Kramer’s first three features, from the old U.S. New Left days; then, there’s Richard Copans, who shot most of his French films after he moved there in 1979; and, there’s also the legendary Portuguese arthouse producer Paulo Branco, as well as filmmaker João César Monteiro, among others, representing his European turn.

The acting styles seem different too. I see you as Doc having a foot in experimental theater, frequently breaking the fourth wall; Monteiro seems to be on a dry run for the João de Deus that he’d play in his own subsequent films, melancholy and a bit impish; and Gallo feels like classic method acting, not far from what young Sean Penn was like at the time. Were you already familiar with them?

PM: No, I didn't know them. Monteiro was gaunt in all respects [Laughs]. It was just a fabulous character that he found. With Gallo, Robert saw his artwork; the fact that he'd only done some acting wouldn't have turned Robert off at all. It was a perfect choice, because he viewed us with such suspicion. I mean, he was really, I think, really glad to have that part, and to move forward as an actor. But he had such suspicion of us, and he took everything very, very seriously. Even though we were striving for a kind of acting style and storytelling that was rooted in our own selves, in some way, he didn't understand that, at the end of the day, it was storytelling and it was acting. When I threw him up against the wall in the film, because before Doc knew he was my son I thought he was an intruder, he was incredibly offended. I tried to say, “It’s just what Doc would have done.” I don't know what that reveals, except that I had the sense back then that he's a very, very sensitive person. I felt it worked really well, as two people who had no idea who each other were, and that they might be father and son.

I communicated with him a week or two ago, for the first time since the film ended, because of these conversations that we're having. I decided to reach out to him. I went to his website and I sent him an email. He responded immediately. He was so thankful. And the tone of the email was so different from the character that he carries on in his website, his whole persona as a Trumper and all this stuff—not at all. It was very warm. You know, he never saw Doc's Kingdom. So I sent him a Vimeo link, and I said, “Now, I think you might find this interesting because your work reveals a self-consciousness about filmmaking. You might be very critical of our leftwing thing, you might not.” I haven't heard back. I sense that the whole right wing, libertarian, Trump thing is as much a kind of bad boy provocateur thing as some kind of serious stance. But I have no idea.

WS: You guys made Doc’s Kingdom in 1986. It screened at festivals to positive response in 1987 and then it effectively disappeared for several years when Paulo Branco lost the rights. It didn’t reach Paris, where Kramer lived, until 1991, and has never appeared on home video in the U.S.

PM: Yeah. Well, he's quite the gambler, not only in the casino. I don't think anybody was surprised.

WS: It briefly played New York in 1988, and when it did, Amy Taubin gave it a pretty brutal review in The Village Voice. She praised it as “jagged, ominous, and undeniably brilliant on the visual level,” but tore into its gender politics as “creepily clichéd patriarchal pap.” Now, I love many things about Doc, but she had a point. It’s a man’s movie where the only significant woman is mostly there to die in the background. You must have read that review at the time. How’d it land, then or now?

PM: Well, I think differently about it now than I did then. I recall being a little bit put off by her review. I've had conversations with Amy about it afterwards, and she even, I think, smiled. The feminist critique of it was very much of that moment, not that it's not true. In other words, that whack needed to be taken, those guys needed a good slap upside the face. I knew it was true then. But I also carried a feeling that it transcended, in a certain sense, and that it wasn't mired in some kind of macho thing. There was a kind of male intimacy that's not recognized in her review. I have conversations with women today about the difference between male and female intimacy. It's a very different thing. Regardless of the critique of patriarchy, which again is true, these are different. My wife's favorite thing to say is that guys need to go fishing, instead of sitting down and talking. But, on the other hand, Robert and I made movies together. It was much more intimate than fishing.

WS: I haven’t seen much discussion elsewhere of your other film credits, but you’ve had an interesting trajectory and I’d love to hear more about it. You show up as a voice in Monster in the Closet, the 1986 horror comedy that I remember watching as a kid. What was that about? Why were you there?

PM: I've never heard of it. I think it's a mistake.

WS: That’s too bad. IMDB credits you with voice, and I loved the idea of you connecting Robert Kramer and Troma, the schlock studio that made The Toxic Avenger [1985]. On the other hand, IMDB doesn’t list Machine Gun McCain [1969], but I know you appear in it.

PM: Well, that was before Newsreel. I was directing theater in the States and then in Europe, working with Living Theatre in Rome. I have this very off-again, on-again relationship to auditions, or trying to be in films. I'm a snob, or I'm lazy, or some version of that. I got a call from someone saying that Pier Paolo Pasolini wanted to interview me for a movie. I love his work, and so I went out to the EUR district in Rome—it was so ironic that the gay Communist/anarchist lived in the fascist EUR.

I got there and knocked on the door, and his mother came out. He's a good Italian boy, he lived with his mother. We met and didn't hit it off at all. But, he said something to somebody and then I got a call for this film. I heard that it had Cassavetes in it [in the title role as a gangster], and that he was actually making the film to get money to make Husbands [1970], I think. It was a fabulous few weeks to hang out with those two guys, Peter Falk and Cassavetes, and play the stupid movie.

WS: Where are you in the film?

PM: One of the two young thugs.

WS: What about Elia Suleiman's Homage by Assassination [1992], a really good, short political film about the first Gulf War, as experienced by a Palestinian exile in New York City? I rewatched that recently and your voice does appear on the radio in it. Was that something you did specifically for the film? Or was he just using an actual broadcast?

PM: Oh, yes, I remember Elia. We met in Rotterdam, when we took Doc’s Kingdom there, or maybe Route One. The festival director hired me for the next couple of years to come over and interview directors, you know, “In Conversation with Directors.” So, I was a regular in Rotterdam for a few years. That’s where I got to know Suleiman.

WS: Let me ask one more of these: how did you wind up in Goodfellas [1990]?

PM: So after Route One, I sort of felt like [my acting career] was over, but I did make a half-assed attempt. I've never been very good as a professional actor, looking for work and doing auditions. I hate that process, but I did go out to the coast and read for a few things. I did a small part in a couple of TV shows and was up for the final to play Nixon in something. I was playing in that world a bit, and in the process of that an agent sent me to Woody Allen's casting director, Juliet Taylor. You have a conversation with her, and if she thinks you might be right, she sends you to meet him. I went to his townhouse on, as I recall, Park Avenue, on the East Side. And, he cast me in his film. I shot a scene. I was a Wall Street character and I had a rendezvous in the park. But then, he cut me out of the movie, so I was never in the film. It's the one where there’s a murder.

WS: Crimes and Misdemeanors [1989]?

PM: Crimes and Misdemeanors, thank you. I got cut from that and somehow, in the process, I got introduced to the Goodfellas team, and did that small part [corrupt judge who lets young Henry slide]. That was an area where I was kind of doing stuff, and I was not very happy doing it—my brief foray into the regular acting world.

WS: Part of Doc presumably died alongside Kramer, who departed tragically young in 1999. But part of him lives on with you, and I wonder about both yourself and Doc in this current moment. I know you’ve remained politically active—just today, before our interview, you were at an anti-MAGA rally dressed as Uncle Sam, a nice twist given that you were the face of armed leftist insurrection in 1970. How do you and Doc navigate 2025?

PM: Well, there are two different thoughts. One is what it feels like now; the other one is, how is that different from that earlier moment? I will say that being 85, and having been active since I was in my late teens, is a journey, and there are pauses. There are sidebars. You get lost. You also look back and realize that you went down rabbit holes and took wrong turns. So these moments—like Doc arriving in Portugal after somehow vaguely escaping from America and then working in Africa, at a dead end—what I appreciate about that is that I knew a number of people like that. I wasn't feeling that so much myself, nor was Robert. We were making a movie. We were not lost, but we were exploring that about ourselves.

That exploring, it felt the same as what Ice was exploring: what would it mean to have an armed insurrection? Then, what does it mean to be lost, at the end of a revolutionary period, and trying to make some sense of this? He’s in the middle of this barren shack on the edge of the river, and he's yelling out, “This is my home.” But what's important for me about that is that we were willing to stop there, and to be honest about dead ends and then find a way to move on.

At this moment, there are dead ends I can't believe, or I can believe. But, I'm struck by the fact that the Democratic party—and I'm not a Democrat, certainly to the left of that—is so inept and so absolutely immobilized in the face of Trump. It is astonishing.

In terms of what's at the heart of your question, after Route One/USA, Kramer and I considered further ideas about Doc: maybe he goes back to Africa, works on AIDS, et cetera. It never came to pass, but I just came back from Grenada. My wife Ricki and I were married there, and I was also there as a reporter during the [1979] Revolution. Then, I was there days after the [Reagan-sponsored 1983] invasion, covering it for NPR. I have a real connection to Grenada, and I started thinking, what if Doc actually lives in Grenada now. Maybe he has a couple days a week when he does some barefoot doctoring, or maybe he runs some classes for nurses or something like that. So then, the Doc story goes on in a way. It begins with this young guy in Ice, then Doc’s Kingdom, then Route One, and then all this time passes, and, my goodness! Here he is.

Doc’s Kingdom screens tonight, April 17, and on April 21, at Metrograph as part of the series “Weird Medicine.” Paul McIsaac will be in conversation with film scholar Mtume Gant after tonight’s screening.