The animated feature When the Wind Blows began as Raymond Briggs’s 1982 graphic novel about Jim and Hilda Bloggs, pensioners in the quiet, leafy Sussex countryside, preparing for the bomb—and for what may come after. Briggs was a contemporary of Ralph Steadman and Gerald Scarfe; yet, compared to his peers’ menacing caricatures, his style was softer and simpler. Still, his work was no less biting, as proved by this adaptation from seasoned animation filmmaker Jimmy T. Murakami.

Murakami was no stranger to state-sponsored trauma. At just nine years old, he and his family were forcibly relocated to California’s Tule Lake War Relocation Center under Executive Order 9066. His sister, Sumiko, died there. His subsequent career in animation took him to UPA in Burbank, Toei in Japan, and eventually to the inauguration of his own studio, Murakami-Wolf, in Dublin.

With grainy color footage of a military convoy thundering down the wet streets of an English hamlet at night, When the Wind Blows opens in the real world. And thanks to David Bowie’s largely forgotten but effectively wistful sophisto‑pop title track, we are firmly planted in the soggy Cold War Eighties. (His “Fantastic Voyage” might have been a better fit, as he croons, “It’s a moving world / But that’s no reason / To shoot some of those missiles.”)

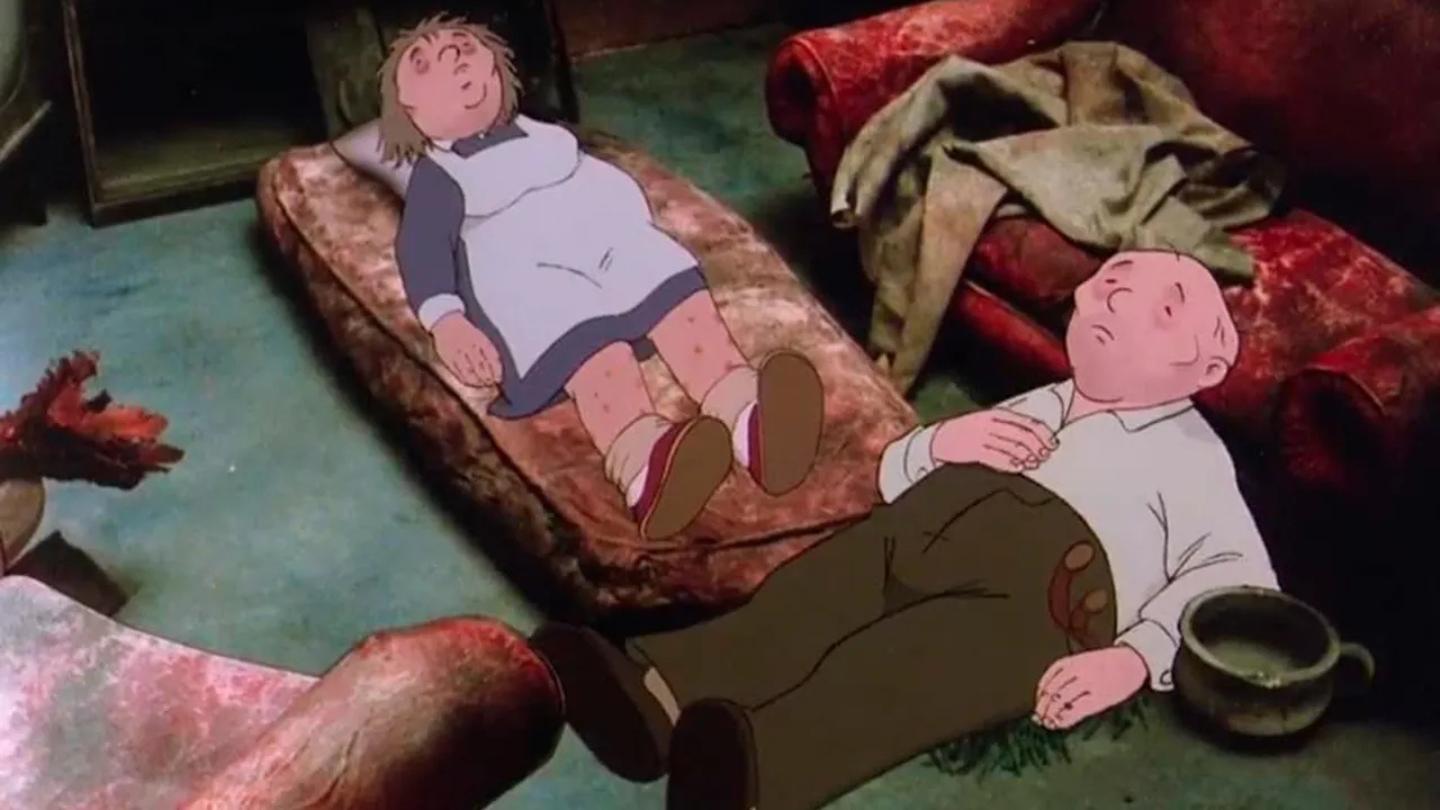

Briggs’s gentle, colored-pencil aesthetic is set against a three-dimensional scale model of the Bloggs’ cottage in the film. This choice by Murakami, though a practical one, gives the Bloggs a nearly spectral presence in their own home. Jim obsessively pores over preparations for a possible nuclear war, reading aloud in his whistling tone from a government-issued booklet that emphasizes constructing an “inner core or refuge” from household items. Hilda, by contrast, worries only about whether he wants his potatoes mashed or as chips for dinner. As the days pass, they reminisce about World War II and “ol’ Joe Stalin,” sharing a nostalgic longing for a seemingly simpler time—one marked by solidarity and clear-cut villains—compared with the uncertainty of their present reality. The film focuses solely on the Blogg’s daily life, leaving the fate of the rest of England—let alone the rest of the world—lingering ominously in the viewer’s mind.

When it finally arrives, Murakami’s vision of the blast differs from Briggs’s original version. In the book, the explosion is represented by a bright white two-page spread, followed by another in which rows of panels slowly emerge from that incandescent blowout. In Murakami’s film, a solarized flash of the Bloggs’ cottage gives way to a sequence that renders the bomb’s destruction and desolation on both a human scale and a mythic, abstract one: a billowing cloud of death, scored by Roger Waters with a grim chug and surges of discordant guitar.

The Bloggs’ watercolor world becomes a burnt-gray, birdless wasteland, yet Jim and Hilda keep calm and carry on. Murakami never condescends their steadfast commitment to normalcy amid the impossible. And, as they search for guidance and cling to the fragile assurances of civilization, we are starkly reminded that there is no guidebook for the apocalypse.

When the Wind Blows screens tonight, January 26, and on February 1, at the Roxie as part of the series “Page to Frame: Animated Adaptations Abound.”