Rainer Werner Fassbinder produced no grand masterwork. While several of his fellow travelers in the New German Cinema movement—namely Volker Schlöndorff, Alexander Kluge, and Werner Herzog—were sustaining an impressive output of one or two films per year throughout the 1970s, none could match the truly frenetic pace of Fassbinder, who was writing, directing, and sometimes acting in as many as four movies per year. This steady stream of stylistically varied, “minor” works makes his oeuvre particularly difficult to decipher, though some have tried (monographic studies such as Ronald Hayman’s Fassbinder: Film Maker and Robert Katz’s Love is Colder than Death are notable efforts to condense and canonize). His eschewal of pretension carried over into his media persona: the image of the overweight, loose-lipped, drug-deranged auteur was a staple of the German tabloids throughout his short, tragically circumscribed career.

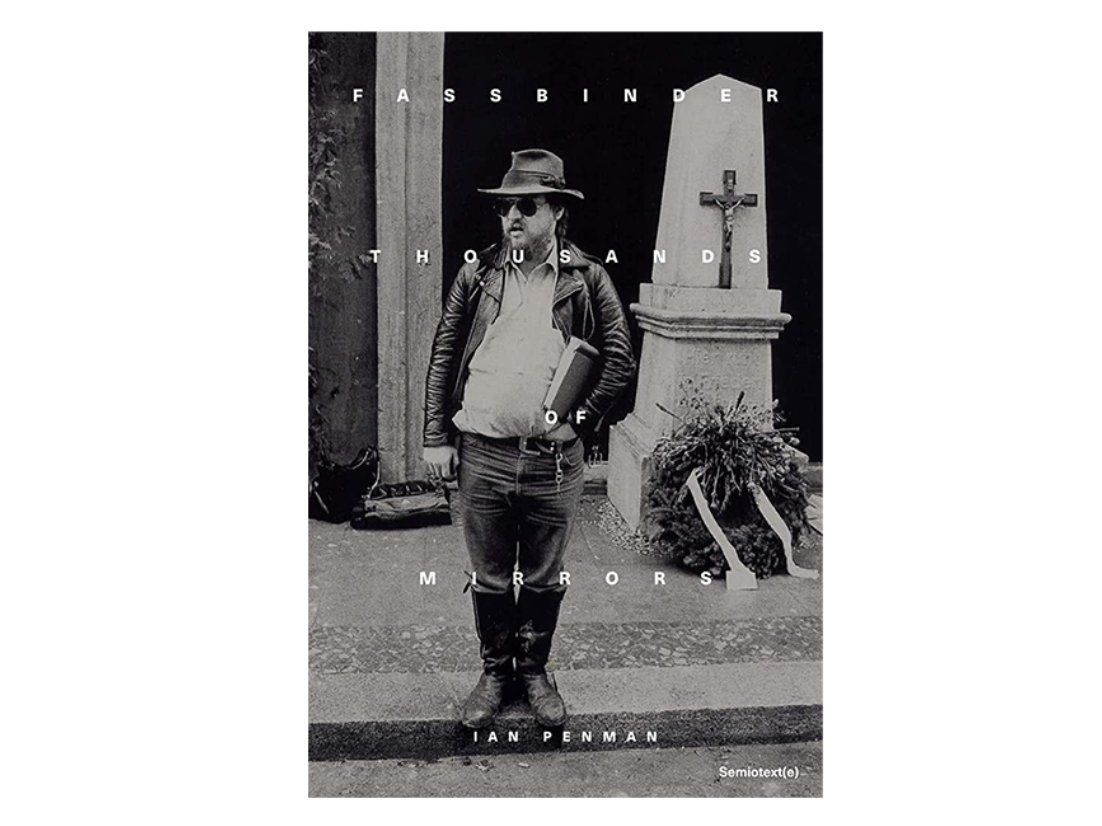

The much-anticipated new book by veteran music critic Ian Penman is an attempt to capture something of the spirit of Fassbinder’s working method. Rather than a linear, A–Z scholarly tome, Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors is composed of digressive, modular units of text arranged in numbered fragments. In them, the director becomes the locus around which Penman’s cultural and intellectual canon orbits, from British post-punk to French theory to German cinema. Extending from the critic’s first encounters with the films during the proverbial “end of the ’60s,” to his recent re-evaluations of his most and least favorites among them, Penman departs from film analysis in the strict sense, taking the unclarity of the titular director and making it his subject.

Michael Eby: Throughout the book, you write that Fassbinder—both his filmography and his status as a quasi-mythological cultural figure—presents a certain degree of interpretive difficulty, even impenetrability; you describe his body of work and legacy as “untidy,” “messy,” “paradoxical,” and “contradictory.” How would you characterize your approach to this problem in terms of your book's construction?

Ian Penman: The obvious answer is: the book doesn't really join up. It's in pieces. It's a mirror smashed into thousands of tiny fragments. There's no central thesis, or through line. I didn't decide on a core “Fassbinder position” and stick to it. I wasn't really up for writing a proper systematic overview or biography—partly because so many of the key Fassbinder people are dead, and thus unavailable for interview, and partly because I don't speak or read German, so I'd be nobody's choice for that role anyway. I did initially attempt something like a conventional study: at the beginning of the first Covid lockdown I sat down, notepad in hand, with the aim of trying to re-view as much of his catalogue as I could find, and see how the films stood up to my long-ago memories of them. But it just felt wrong, on so many levels. It felt like I was playing a role in some Netflix Euro thriller—the damaged ex-cop who returns to an unsolved mystery, ready to dig up the body and find an explanation which contradicts the official verdict.

So I thought: Well, what would Fassbinder do? (Aside from immediately having more drink, drugs and cigarettes, all of which I now personally abjure.) The idea of following a self-imposed “in the spirit of Fassbinder” deadline turned out to be extremely liberating. It's what might be called an anti-iconic approach. You want him to be honored, but not to become safe and congealed. The image I had in mind for the book was . . . a disco ball. Kitsch but illuminating. Thousands of tiny mirrors. Slivers and ghosts and corner-of-the-eye glints. Reflections of all kinds, from hidden sources. A light in the darkness, like cinema.

ME: The book is not only about Fassbinder and his milieu but about you and yours; in many ways, it sketches your introduction to U.K. underground culture in the 1970s. These were presumably formative years for you—when you first moved to London and began work as a critic for the NME. I like your analogy that Fassbinder is, for you, “what Baudelaire was for Walter Benjamin.” In what way is Fassbinder a “prophet” in that sense? What compels you to examine this period and to illustrate and present it for us now?

IP: I guess it's to do with a cusp moment in the ’70s, untidy and bristling with wild energies and brazen experiments and odd contradictions. Stuck between the more obvious banner headlines of the ’60s and ’80s: idealism vs. pragmatism, revolutionary fervor vs. entry-ism, soft drugs vs. hard, let's blow things up vs. let's make lots of money. In reality, the differences between epochs are never really that clear cut, but the ’70s definitely retain a dark, complex, largely unexplored fascination. (This is especially true of Italy and Germany.) Fassbinder explored some of the more poisonously alluring undercurrents; what's perhaps more surprising, given his work rate, is just how prescient many of the films now feel. Just look at World on a Wire [1973] and In a Year with 13 Moons [1978] and The Third Generation [1979].

Taking a wider view of that late ’70s moment, I think a lot of us imagined all kinds of things might still be possible. Revolution was still a dream—in both senses of that ambiguous word—but to turn it into reality involved hard, dull, repetitive, patient, laborious work. A lot of us bailed for art, drugs, and various redoubts of “the personal is political”; I'm still not sure what I think of this. There are people in the book who exemplify a different approach to Fassbinder (and his whole “live fast, die young” ethos), having to do with survival against the odds, productive longevity, keeping your ethics or politics or ideals intact. People like Genet, Alexander Kluge, Straub/Huillet.

ME: You argue that many of his films deal with specifically German themes—the obvious examples being those of the so-called BDR Trilogy, each of which deals with the anomie of post-war reconstruction—but you also stress that his admiration for Douglas Sirk and Hollywood is well known, and that his films seem to exude a fascination with the surface appearance of a new kind of uniquely American consumer culture. In what way might those American sensibilities conflict with his German ones?

IP: Do they necessarily conflict? A lot of U.S. attitudes were after all conceived and fashioned in the first place by European refugees. What would Hollywood have been without them? Think of the flair and innovation of Billy Wilder and Fritz Lang alone, not to mention Robert Siodmak and Douglas Sirk and many others. They wrote the handbook for so much U.S. culture to come. A lot of what we take to be specific American attitudes (wisecracking and sexy, cynical and fatalistic) are their legacy. Where would post-war America be without its influx of European rocket scientists, designers, psychoanalysts, and filmmakers?

ME: The book is not without criticism of Fassbinder's films; in fact, you write at one point that revisiting certain of them was a “painful experience,” and that there were a few where you didn't make it to the end. What makes a Fassbinder “misfire” versus a masterpiece?

IP: I'm not sure I trust the word “masterpiece.” It has this odor of sanctity and airless veneration, aspic and old lace. I do find some of Fassbinder's misfires more enduringly fascinating than his own or other peoples' masterpieces. There's a faint dialectic in the book of the young me and what it may have been I originally saw in Fassbinder, versus the older, more sober me, thinking about him now. In certain respects, my admiration for him has just grown exponentially. The younger me probably had something of a child's naïve conception of how cinema actually got made, of how things were conceived, written, produced. A marvelous fairy tale dream! Decades on, I know how difficult it is to get anything made, in any medium, especially if it involves any kind of personal vision (and other people's money). What Fassbinder achieved was miraculous.

ME: You frequently discuss the role played by technology in certain Fassbinder films, most overtly but not exclusively in The Third Generation and World on a Wire. This is a relatively underexplored theme of his work, especially compared to those of sexual mores, class relations, and racial tensions, not to mention the identification of various autobiographical elements. Does Fassbinder have a “view” on technology? His obsession with the cinema and television suggests that his position is not straightforwardly pessimistic. Further, might his preoccupation with the new media environment of his time also be reflected in the “artificial” feel of his movies?

IP: It made me very happy to find out Fassbinder was a huge TV addict—a set in every room, broadcasting 24/7. As I say in the book, among all the very many unrealized Fassbinder projects the one that really makes me pine was his proposed TV special on Freud. When he made World on A Wire (even the title is great) and The Third Generation (ditto) he definitely tapped into something. The mood is like Philip K. Dick: flashes of future shock here now today. Tech anxiety; fractured identity; group hysteria. I think it's quite telling that he's so on the money with this jagged, downbeat sci-fi; whereas, when he tried to do proper old-fashioned drama with Berlin Alexanderplatz [1980] it has to be counted something of a failure: too monolithic, too in thrall to the past and an old-fashioned idea of ”quality TV.” Maybe if he had lived (and sobered up), he would have really taken to digital culture—lighter cameras, quicker editing and post production, so on. Maybe his work rate would even have increased!

In terms of my own life: I was part of the first generation of TV babies, and one of the last generations who grew up in tatty repertory cinemas. When I first moved to London in 1978 it still had a vast hinterland of unofficial cinemas: cartoon cinemas, soft porn cinemas (there was one in Soho that seemed to screen nothing but Swedish “educational” films and a series of badly re-edited Russ Meyers), and a whole range of what we used to call “fleapits”. I remember going to see an afternoon showing of Fritz Lang's Die Nibelungen [1924] at The Electric in Portobello Road, where the only other attendees were a scattered circle of snoozing tramps & winos; this was not uncommon. Higher rents, Thatcherite policies, and the rise of the whiz-kid property developer all put paid to this prelapsarian world. The idea of repertory programming is now largely the domain of digital streaming—I've no idea what this presages. All that is solid melts into . . . where?

ME: During his life, he occupied an ambivalent, or at least ambiguous, relationship to German leftism—especially the Red Army Faction and Baader-Meinhof—which is carried over into the films: there is a wide gulf between the ridiculous revolutionary caricatures of The Third Generation and his more forthrightly partisan contribution to Germany in Autumn [1978]. Do you see any consistent political content or ethos in Fassbinder's work?

IP: While he was alive, it was his perceived inconsistency that alienated many sectors of the audience—left and right, gay and straight. His politics were considered way too much by some people, not nearly enough by others. This seems characteristic.

I spent quite a bit of time looking at images of Fassbinder, and couldn't help but notice something: in all the photos of late-period, fucked-up Fassbinder, more often than not he is beaming, wearing the widest and sweetest little-boy smile. In earlier photos of the more radical, intense, take-no-prisoners Fassbinder, he always seems to be scowling. I draw no conclusion from this.

On the one hand, he contained multitudes; on the other, I emerged from writing the book with a sneaking suspicion that, essentially, the 37-year-old Fassbinder who slouched into death may not have been much different from the young, bushy-tailed Fassbinder starting out. I'm not sure he “grew” or “matured” or “developed” at all. Which I have no real problem with, I have to say. I can see this same quality in many other artists I revere. (And also maybe in myself.)

Ian Penman will appear tomorrow, May 9, at Light Industry to read from Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors and screen film clips.