Though depictions of murder were commonplace in cinema through the first half century of its existence, it was seldom handled in a comedic fashion. Comedy could be dangerous, even violent, but the act of homicide was typically relegated to genres that operated in a more serious space: westerns, swashbucklers, gangster pictures, espionage sagas, and police procedurals. Assassinations were often represented in a political or historical light, as in the films that depicted the life and, ultimately, murder of Abraham Lincoln; these include D.W. Grifith’s biopic Abraham Lincoln (1930) and Anthony Mann’s amusingly titled The Tall Target (1951). The first comedic film to prominently feature a hitman might be Robert Day’s The Green Man (1956), which takes its title from a hotel in which an assassination is to take place until the hit is interrupted by a vacuum cleaner salesman.

With its dry humor and Alastair Sim (at the time, best known for portraying Scrooge in 1951’s A Christmas Carol) as its lead, the sardonic bent of The Green Man signaled a change in how murderers would be portrayed moving forward. But hitman comedies found footing overseas before landing in Hollywood with films like Italy’s Mafioso (Alberto Lattuada, 1962), Japan’s Murder Unincorporated (Hiroshi Noguchi, 1965) and Branded to Kill (Seijun Suzuki, 1967), and the United Kingdom's The Assassination Bureau (Basil Dearden, 1969). These films offered distinct territorial renderings of hit men, with much of the humor behind their characters and narratives coming from their respective locales.

In the United States, the 1970s ushered in a new era of films that were freer than ever before, thanks in no small part to the dreaded production code falling at the tail-end of 1968. One of the more harmonious results of this was a potent mixing of violence and comedy that wouldn’t have pushed past the censors in decades prior. Major movie stars seized the opportunity to star in such films, and two of the first studio-produced hit men narratives to come out of Hollywood were Michael Winner’s The Mechanic (1972), with Charles Bronson in the lead role, and the British director Douglas Hickox’s Brannigan (1975), which starred John Wayne.

The Mechanic is the more serious of the two films and feels indebted to Italian Poliziotteschi films while featuring more ludicrous action than said genre fare. Bronson stars as a hitman with a penchant for making his murders appear to be accidents. It’s a bravura turn from Bronson, who was most well known for his work in westerns and organized crime narratives at that point. In The Mechanic, he embraces the simultaneous goofiness and cool that became his trademark in the following decade, particularly in the Death Wish sequels. Brannigan, a fish-out-of-water comedy that transplants the all-around American John Wayne to the streets of London, is largely an excuse for Wayne to appear clueless in a foreign land, but it occasionally mirrors the comedy in The Green Man in which murders—both attempted and realized—are delivered with a gallows humor.

All of the films mentioned thus far were critically and/or commercially successful to varying degrees, but none as much as John Huston’s Best Picture nominated wise guy rom-com Prizzi’s Honor (1985), which earned Anjelica Huston a Best Supporting Actress Oscar and much of its cast and crew, including her co-star Jack Nicholson and Huston himself, nominations. Huston’s film, based on the novel by The Manchurian Candidate (1962) writer Richard Condon, ups the hitman ante by featuring two assassins as its leads. This is made all the more complicated by the fact that they fall in love with each other. Prizzi’s Honor was not only critically revered and a box office hit, but its meshing of romance conventions and crime comedy predicted other assassin love stories such as Coldblooded (1995), The Whole Nine Yards (2000), Mr. & Mrs. Smith (2005) and Grosse Pointe Blank (1997). The latter of which is one of the great and largely unheralded crime comedies of its, or any, era.

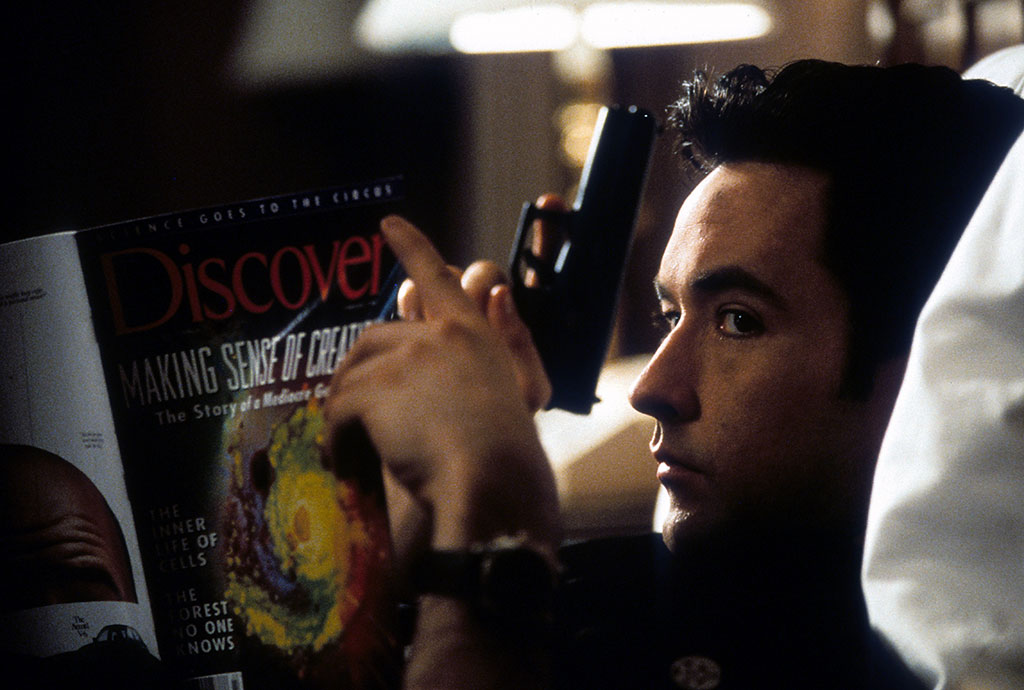

George Armitage’s Grosse Pointe Blank is an uneasy marriage of romantic comedy conventions, nostalgia for ‘80s high school movies, and stylized violence. It was also a passion project for star John Cusack who produced and co-wrote the screenplay. Like many of the more eccentric genre amalgamations that hit American multiplexes in the 1990s, Armitage’s film is defiantly difficult to taxonomize. It’s an empathetic and often very funny comedy about a hitman attending his high school reunion in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, which, as fate would have it, doesn’t go according to plan. It mixes some of the fish-out-of-water elements of Brannigan, the dark humor of The Green Man, and the romantic flourishes of Prizzi’s Honor into a concoction that really hasn’t been mirrored since, even if films like the aforementioned The Whole Nine Yards have made a sincere attempt.

The 2000s were rife with crime comedies, with the assassin archetype not hard to find in just about any year. Films like Nurse Betty (2000), Love and a Bullet (2002), Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2002), The Matador (2005), You Kill Me (2007), War Inc. (2008), and In Bruges (2008) all pushed what was once a niche sub-genre of a sub-genre into the mainstream alongside more serious films like Robert Rodriguez’s legacy sequel Once Upon a Time In Mexico (2003), the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men (2007) and Michael Mann’s Collateral (2005). As with decades prior, many of these found their laughs at the darker end of the spectrum, particularly the decidedly gorier entries like Nurse Betty or In Bruges, which pushed for a post-Tarantino emphasis on bloody humor which lent itself well to the subject matter at hand. But if anyone truly pushed the limits of the content, and its audience, it was the noted provocateur William Friedkin in the early years of the following decade.

Killer Joe (2011) originated as a play by Tracy Letts before making its way onto (only a few) American movie theaters, thrust before moviegoers eager to see the new Matthew McConaughey picture. Wearing its excesses with pride, Friedkin’s film features McConaughey as the titular Joe, a police officer dabbling as a hitman who takes a job to kill the mother of a young man who is looking to cash in on her insurance policy. To say that it gets darker from there would be an understatement. Friedkin’s penchant for explicit sex and violence, oftentimes mingling together in the same scene, earned the film an NC-17 rating, something no other film mentioned thus far had garnered from the MPAA. Yet, underneath all of the brutal beatings, sexual humiliation, and uncomfortably graphic nudity, there exists a sharp satire of American violence.

There exist a plethora of other hitman-comedies alongside Friedkin’s film, such as the UK flick Wild Target (2010), the Razzie-winner Killers (2010), the star-studded RED (2010), the indie-teen comedies Violet & Daisy (2011) and Barely Lethal (2015), the hitman rom-com Mr. Right (2015), the Hungarian-wheelchair-assassin-exploitation-film Kills on Wheels (2016), the rambunctious crowd-pleaser The Hitman’s Bodyguard (2017), and Liam Neeson’s chilly, darkly funny, remake of Cold Pursuit (2019) in which he eliminates assassins with the aid of his trusty snow plow. We’ve come a long way from 1956’s The Green Man over the past six decades, but if Day’s film is the urtext for what is considered the hitman comedy, everything since then has reinforced the notion that these characters can actually be funny. The jokes may have gotten dirtier, the sex more lurid, and the violence more realized, but ultimately the punchline remains the same: being an assassin is a job and just like any other profession, it’s riddled with drama. Or, as John Cusack’s character states in Grosse Pointe Blank after the woman he loves calls him a psychopath: “Psychopaths kill for no reason. I kill for money. It's a job. That didn't come out right.”

Trigger Happy: Hit Men with a Punchline runs May 10-May 23 at the Paris Theater. Grosse Point Blank screens tonight, May 19, on 35mm.