For nearly four decades now, the Cote d’Azur’s foremost festival of experimentation has occupied a cherished niche in the international avant garde filmmaking community. Just down the road a spell from Cannes, France’s second-largest city boasts a renowned showcase of arthouse B-sides. Founded in 1989 as the “Marseille Festival of Documentary Film,” FIDMarseille has since re-branded and expanded to include hybrid/non-fiction and the errant underground narrative film. A cursory glance at their program archives boasts a rogue’s gallery of cinematic artistry: where else would you see Roger Corman, Chantal Akerman, Lav Diaz, or Albert Serra under the same banner?

This summer, the adventurous programming staff at FID added another legend to their stable: your own humble Screen Slate correspondent. Earlier this month I had the pleasure of premiering my sophomore effort, Revelations of Divine Love, as the only American film in the International Features Competition. The invitation arrived this spring, the day Mercury went out of retrograde, and nearly a year to the day after our final pick-up shoot during the 2024 solar eclipse (astrology: real!). If you had told me last year, as I shlepped a giant foam cross to Plumb Beach off the Belt Parkway, that this mishegoss would send me to the South of France, I’d have laughed in your face. Every film could be construed as an experiment, surely, but I did not consider my second feature to be anything of the kind. Still, who am I to argue with divine provenance—and the staff of a celebrated international festival? After eight long years of starts and stops and re-starts and re-shoots, it felt good to finally have an answer when someone asked at parties, “What’s happening with your movie?”

The last time I premiered a feature film was in the summer of 2017, when Donald Trump had recently been elected and Gracie Mansion was on the precipice of a “socialist” takeover. Whether these local political changes and national tragedies are the Butterfly Effect-esque result of my filmmaking career, I’d rather not speculate, but every premiere comes with its own unique set of anxieties. In placing my flawed-but-loveable first film, A Feast of Man, among the hospitable staff and eager audiences at Birmingham, Alabama’s Sidewalk Film Festival, I preemptively anticipated a chilly response to my especially coastal and elitist brand of filmcraft. Nevermind that A Feast of Man was filmed well inland at an Air BnB in Hudson, New York, for a shoestring budget of less than $50,000: I had, I’m ashamed to admit, a rather narrow view of city life below the Mason-Dixon. Suffice to say the audience response was quite the opposite, and I’m pleased to report that humble pie tasted just fine.

Still, when staring down the prospect of screening my life’s work before an international audience, these aforementioned fears kicked into an even higher register. Despite my Los Angeles upbringing and half-life spent in New York City, I consider myself to be rather provincial. I’m not well-traveled, my French is a disgrace, and I’ve never covered an international film festival—let alone attended one for the world premiere of my new film. While other people might delight in globe-trotting, I’ve spent the better part of the last decade stateside trying to get a low-budget 14th-century period piece in the can. That this commitment to the seventh art netted me the trip is, of course, the best kind of “me reaping, me sewing” moment.

Fortunately, I had secret weapons at my disposal: enthusiastic members of our cast and crew in attendance—star Tessa Strain, AD Sydney Buchan, producer Kate Stahl, DP Gabe Elder, and art director Grant Stoops—and the privilege of representing the Five Boroughs. If there’s one thing I learned in my years of high-end retail, it’s that the French love New York City—and more than a few folks I met were especially intrigued by Gracie Mansion’s latest socialist interloper. Left to fend for myself at a “no plus ones” opening night reception, I knocked back two glasses of remarkable rosé and waxed rhapsodic about “notre prochain maire, un socialiste Muslim,” much to the novel delight of anyone who’d listen.

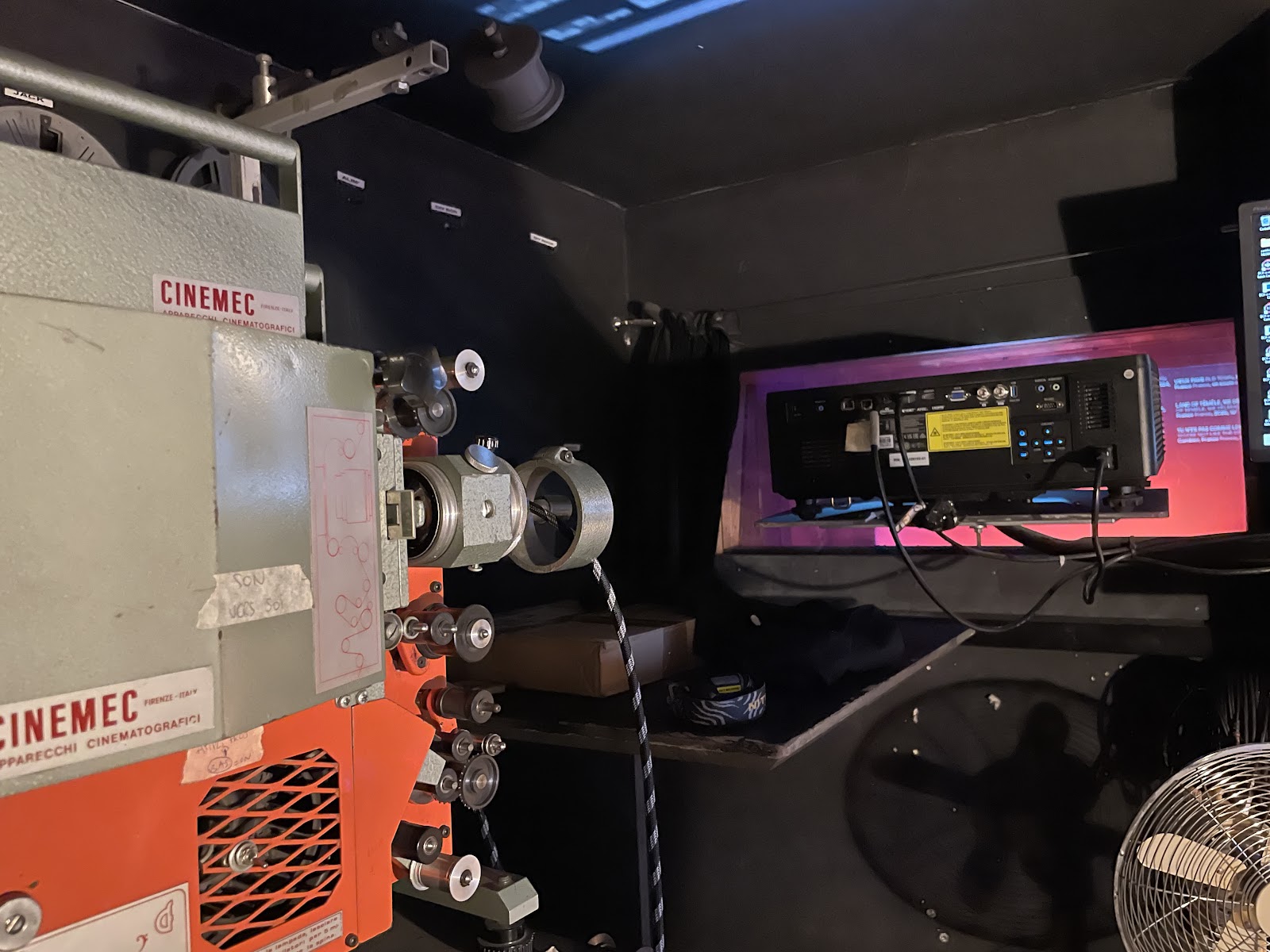

True to my filmmaking practice of inciting global crises, the first full day of FID was marked by misfortune: wildfires had broken out in the forests outside the city, covering Marseille in a thick blanket of familiar, SoCal-style smoke. Undeterred by natural disasters—I am a Californian, after all—I spent the better part of the afternoon dropping off poster-postcards at record stores, coffee shops, and the other festival venues. And it was one such drop-off, at microcinema Videodrome 2, where I encountered a few fellow travelers. Spotting a coterie of likeminded anarchists out front, I introduced myself to the venue’s projectionist and, in so doing, discovered we had many mutual acquaintances back in New York City. When I mentioned my involvement with Brooklyn’s Spectacle theater, my new pal turned to his colleagues and exclaimed “Videodrome 2 est le Spectacle du Marseille!”

From that moment, until the end of the festival, every day was a tourbillon of frantic activity. Blessed by jetlag, I’d wake at dawn and hoof it to a café and try to order iced coffee (one barista, upon receiving my order for “un cold brew avec espresso,” shook her head and replied “c’est fou!”). Mornings were reserved for religious sightseeing expeditions—to the Old Major Cathedral, or the crypt at the Abbeye Saint Victoir—before an outfit change, a lunch, and a screening or two.

Our first of three screenings was on day two, at Les Varietés, a lovely mini-plex just off the main drag. Buoyed by the publication of my interview with fellow cineaste Sofia Bohdanowicz in Filmmaker Magazine, the whole escapade finally began to feel like something big. Despite my protests leading up to the festival, I ultimately decided to sit and watch my film for the last time, and delighted in hearing laughter from the audience during the appropriate scenes. In the weeks leading up to our first screening, I wound myself in knots with worry about the post-screening Q&As. Sweating bullets in the lobby, festival programmer Claire Lasolle, who’d invited us to screen at FID, introduced me to our interpreter, Katherine. Fortunately, we hit it off like gangbusters: she and Claire were effusive in their praise of the film, and Katherine was able to keep up with my frantic babbling. By the time we met again for the second talkback, a few days later, we’d found our groove—and, if my public school French comprehension is any indicator, she relayed my special brand of bullshit with finesse.

The excitement and wonder of a new city was a powerful lure, and I continuously had to remind myself that I was here for a festival, not a vacation. Aware of my own inability to be in two places at once, I fed my nagging need to wander on cinematic trips across water and land. Earning the “Prix du Centre national des art plastiques,” French director Philippe Rouy’s Thousands of Years of Absence uses the fictional “Ukushima collective” as a contextual container for an island-hopping tour of Japan’s vast outer archipelagos. Per the film’s invented mythology, a group of activists were compelled by the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster to document every Japanese island for posterity in a post-human future. Mining the history of Japanese anti-nuclear activism as a framing device isn’t exactly my idea of tasteful filmmaking, but Rouy’s vérité portraits of plaintive island life charmed me nonetheless. Shot and starring 7 Walks with Mark Brown cinematographer Sophie Roger, Love on the Bramble Path follows the filmmaker as she “walks the bounds” in and around her idyllic farm. “Provincial” in the true, geographic sense, this rusticated self-portrait of the artist among the changing seasons recalled—to me, at least—the familiar rhythm of monastic hours. Deeper into the hinterlands, Russian director Artem Terent’ev’s A Knife in the Heart of Europe played like a post-Soviet Gummo in miniature, shadowing a trio of nihilistic youths in wartime.

But even far from home, I couldn’t avoid glimpses of NYC’s little movie colony. It was a pleasant surprise spotting For the Plasma director Bingham Bryant among the central trio in Portuguese filmmaker Rita Azevedo Gomes’s Fuck the Polis. Using her epistolary account and 30-year-old footage of a Greek vacation as a point of departure, Gomes stitches together a meditative journey through the annals of memory. Polis ultimately nabbed the festival’s Prix Georges de Beauregard International—irrefutable proof of the jury’s penchant for cinematic travelogues.

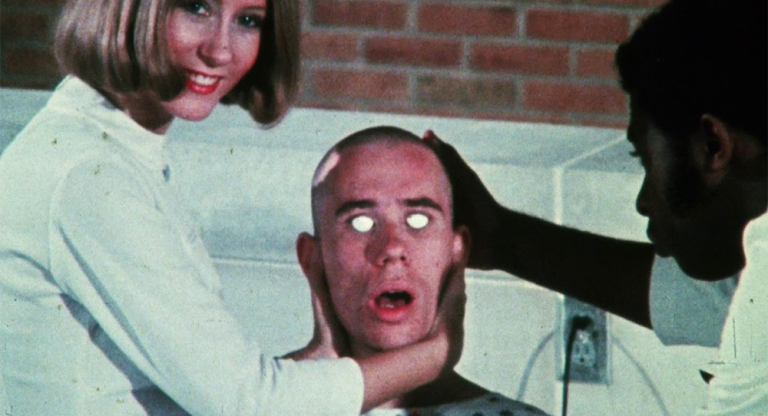

FID is a premiere festival, and the staff’s commitment to avoiding big tent releases affords them considerable curatorial leeway. I was especially struck by the inventive style on display in Natasha Tontey’s Primate Visions: Macaque Macabre, an allegorical fantasia about a rogue primatologist and her macaque collaborators. Believe me, you have not experienced true cinema until you’ve seen two actors in remarkable monkey suits emerge from a giant, red ass. As a fine testament to the festival’s emphasis on hybrid docu-fiction, Clemente Castor’s Cold Metal wove rich, vibrating visuals of Mexico’s rural cave networks with a missing person ghost story, following protagonist brothers Oscar and Mario as they search for each other through their respective subconsciousnesses. Hewing closer to the straight-ahead documentary mode, but told with a keen and clever eye for composition, was Lucas Kane’s Jacob’s House, a short 16mm portrait of Brooklyn artist Jacob Eye fighting tooth-and-nail against his landlord’s eviction proceedings. The film, which opened with a title card decrying the violence of private property, nabbed a well-earned accolade from the student jury during the festival’s awards ceremony.

Having spent more than a week living my dream come true—a film premiere in the South of France!—while the world around us burned, the closing night awards ceremony felt like the perfect place to exercise my cognitive dissonance. Evidently I was not alone: every filmmaker reserved some, if not all, of their remarks to voice their full-throated support for the Palestinian people in their struggle against Zionist slaughter. Filmmakers from Argentina cited their government’s destructive austerity policies, filmmakers from Germany castigated their leadership for abetting genocidaires. The polycrises of capitalism are unavoidable, whether at a sidewalk bistro or in the plush seats of a local multiplex, and any artist who pretends they aren’t is a sucker and a fool. Hearing other filmmakers’ struggles to make work in a perennial garbage fire, to resist state oppression, and to find cause to celebrate in the face of despair dispelled my lingering sense of hick naïveté. Recounting my own journey with this film—and the aforementioned crises that dogged my last premiere—offered a release from American exceptionalism, a reminder that there are no borders in the fight. How this bonhomie will play out back home—wherever home is for us lucky chosen—I can’t pretend to predict. What I can be certain of, based on the 10 days I spent with the filmmakers and workers at FIDMarseille, is that when the going gets tough, the tough make movies.