Beginning in the 1950s, Akira Kurosawa turned to the great works of European literature, first adapting Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot in 1951 and subsequently William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Macbeth six years later. Kurosawa later tackled two further works by the Bard—Hamlet in The Bad Sleep Well (1960) and King Lear in Ran (1985). Retitled Throne of Blood, Kurosawa’s version of Macbeth transplants the story from 11th century Scotland to Japan’s war-ravaged Sengoku era. Medieval stone castles are replaced by wooden fortresses, and flowing tunics give way to riveted armor. Though inspired by musha-e scrolls, the film’s most striking features are its meticulously detailed costumes and the grand choreography of massed hordes. Otherwise, Throne of Blood’s compositions possess a starkness unique to Kurosawa in which the screen’s empty spaces heighten the crisp, planar character of the director’s epic mise-en-scène

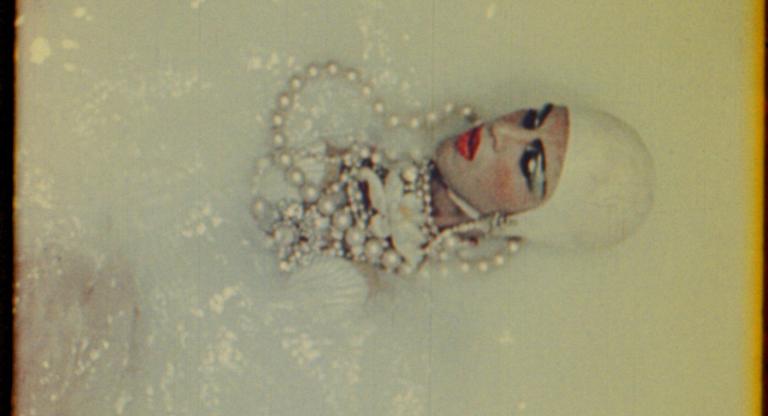

In place of craggy Inverness stand the fog-shrouded, ashen foothills of Mount Fuji, whose forbidding expanse lends the film a mythic austerity. Toshiro Mifune plays the proud warrior Washizu, whose fateful encounter with a forest spirit—Kurosawa replaces the play’s three witches with a single, androgynous wraith—sets him on a path toward madness and murder. Mifune’s performance is a masterclass in controlled ferocity, his explosive physicality contrasting sharply with the eerie stillness of Isuzu Yamada as Lady Asaji. Asaji moves with a spectral glide, her placid, almost affectless presence exerting a hypnotic hold over Washizu. Kurosawa seems less concerned with the poetry of Shakespeare’s dialogue than with illustrating the ruinous descent of his protagonist.

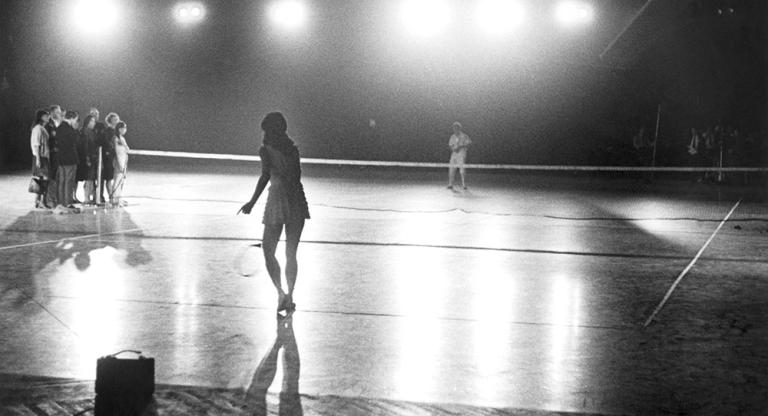

The film’s interior scenes reveal the strong influence of Noh theater. Characters move with ritualistic precision, and Mifune contorts his face into mask-like expressions of terror and rage. Faithful to its source, Throne of Blood leaves most of its violence offscreen, a restraint that makes moments of explicit brutality—whether a sudden spearing or the film’s climactic storm of arrows—all the more devastating.

It is no wonder that Kurosawa regarded The Tragedy of Macbeth as his favorite Shakespearean play. The narrative of a lone figure whose unchecked ambition inevitably leads to self-destruction, unfolding within a world dense with symbolic meaning and structured around ceremonial pageantry, mirrors some of the thematic and visual preoccupations found in much of Kurosawa’s cinema. So steeped in paranoia that omens and hallucinations weave into the fabric of reality, Throne of Blood opens and closes on a barren vista marked by a solitary headstone, ultimately underscoring the grim axiom spoken by the forest spirit, a line that could serve as a précis for many of the auteur’s greatest works: “Men are vain and death is long.”

Throne of Blood screens this Saturday, February 15, at New People Cinema, presented by the Roxie, as part of the series “Nippon Vibes: Japanese Cinema Weekend at New People.”