“Robert Redford, you are a god to me,” Gregg Araki announced at the premiere of I Want Your Sex. But what happens when god is dead? The question hovering over this year’s Sundance was not whether Redford still mattered—which he clearly does, according to the many anecdotes proffered in every introduction—but where, exactly, does Sundance go from here? In one sense, we already know the answer. Beginning next year, the festival will decamp to Boulder, Colorado, a move that has been framed as pragmatic, future-oriented, even revitalizing, despite the fact that an increasing number of filmmakers and regular industry folk I spoke to plan to skip the first few years while things sort themselves out. (Apparently, I am told, Boulder has even fewer acceptable lodgings and infrastructure than Park City.)

If the future is unsettled, Park City reflects it. To a first-time visitor, the town appears wholly unreal—curiously staged and bereft of magic. Newly constructed plazas sit at the foot of the mountains, which, this year, were conspicuously bare of snow, heightening the sense of artifice. (The festival’s wonkiness was only reinforced by what passes for “theaters” here, including a conference room inside a DoubleTree.) Within hours of arriving and as I was on my way to pick up my badge with a group of women of color—we were all part of, or formerly a part of, Sundance’s Press Inclusion Initiative, a diversity endeavor—a man in a pickup truck stopped in the middle of the road to yell, with expletive-laced clarity, for us to get the fuck off the street. It was an abrupt, bubble-bursting welcome to Park City, made grimly legible later when news broke two days later that Florida congressman Maxwell Frost had been punched in the face by a local racist who favored deportation.

The assault unfolded at a party on Main Street, where brand activations, industry talks, and general churn, including an anti-ICE protest, took place. Meanwhile, press screenings take place a 35-minute walk northwest, and many of the bigger premieres are staged at a high school several miles in the opposite direction, as if daring you to declare your priorities. On a day-to-day basis, I was forced to choose between the obligations of cinema and everything else. One writer candidly told me that she planned to spend an entire day “heckling people on Main.” To come to Park City to watch and discover movies seemed beside the point. The divide between cinemagoing and socializing on the ground mirrored a more fundamental split in the festival slate: between story and art. To lament this risks sounding pious, even ungenerous, and yet it is difficult to ignore.

Films that managed to thread the needle between narrative clarity and formal ambition were few and far between in my viewing. Among them was Closure, a largely wordless documentary by the Polish filmmaker Michał Marczak about a father’s search for his missing son, who may have disappeared into the river. Rather than indulging in the often sensationalized details of true crime, the film redirects attention to the unbearable weight of grief inherent in the search itself. Meanwhile, Adam and Zack Khalil’s documentary feature Aanikoobijigan adopts a more instructive mode than is typical of the brothers, alongside more experimental tactics like kaleidoscopic visuals and metaphoric evocations of time, or the pulsing electronica that nearly drove one viewer out of the theater, in order to foreground the idea of tribal sovereignty concerning the repatriation of human remains.

Unlike past years, there was no clear consensus breakout—no A Different Man (2024), no Get Out (2017). Beth de Araújo’s Josephine came the closest. Its bracing premise centers on the psychic aftermath of an eight-year-old girl (Mason Reeves, compared to Meryl Streep by the moderator) who witnesses a rape in Golden Gate Park and is left to fend with parents who exhibit a bewildering indifference to therapy. About two-thirds of the way through, the power cut out in the theater just as a character gripped a knife and moved down a hallway with grim resolve. The imagined violent consequences wouldn’t have been an implausible ending given de Araújo’s previous film Soft & Lovely (2016) and her reliance on aggressive gambits designed to unsettle. Some in Josephine, like the lingering specter of the rapist, are productive, while others, like the aforementioned knife-brandisher, are not. Overall, de Ararujo successfully lands a narrative resolution, solving the trauma plot as best as one can hope for with such thorny material. Still, the genre borrowings cheapen the effect, overcranking the drama into something loud rather than something affecting.

Familiar negotiations of art and commerce, as well as taste and ambition, presented themselves in some of the marquee titles, such The History of Concrete, the feature debut from John Wilson. The 100-minute documentary is reliably satisfying, opening with an outrageously blunt seminar on how to manufacture a Hallmark movie and concluding with a meditation on life, rhyming elegantly with the final episode of the most recent season. Such expansiveness, however, was notably absent in The Gallerist. Cathy Yan’s Art Basel Miami-set farce, in which Natalie Portman, as the titular professional, must pass off the accidental impalement of an influencer as part of a newly launched exhibition, was trailed by such dismal early reactions that the film itself benefited from the lowered bar. Watching Portman cooing around like Nicole Kidman and Jenna Ortega flail demonstrably as her assistant was less of an affront than expected in the forgiving light of the morning after the premiere. The script is astonishingly blunt, populated by characters who repeatedly ask, “Do you know what this means?” before explaining precisely what things mean. An airless, oddly hostile work, gesturing toward cultural critique while remaining wholly incurious about the art-world culture it depicts, The Gallerist is not unwatchable, just aggressively shallow.

Gregg Araki’s I Want Your Sex fares better, largely because it knows exactly what it is. Operating closer to the gleeful anarchy of Kaboom (2010) than the bruised intensity of Mysterious Skin (2004), the New Queer Cinema forebear offers a giddy diversion about a provocative artist (Olivia Wilde) and her professional and unprofessional entanglement with a naïve intern (Cooper Hoffman). Written years ago, the film unmistakably bears that dated stamp of its moment: its approach to sex is more amused than truly exploratory, more comic than erotically charged, though Wilde and Hoffman are a genuinely fun pair, sparring scene by scene, smirk by smirk, spank by spank. During the Q&A, Chase Sui Wonders, who is short-shrifted with a rather ungratifying smaller role in the film, remarked on the prudishness of her generation. Taken in that light, the film gains more social currency than it initially appears to have. Broadly speaking, sex across the Sundance lineup felt more conspicuously throwback.

The Invite, Olivia Wilde’s film, which ultimately sold to A24 for a reported eight figures, is based on a Spanish film by Cesc Gay that has already survived multiple remakes. In it, two San Francisco couples endure a long evening together, à la Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf or Carnage (2011), and the film unfolds as a polished exercise in performance and timing. The risible comparisons to the films of Woody Allen have merit, but only insofar as they too revolve around beautiful people in tastefully appointed apartments, trading lengthy monologues and the occasional piano ditty about love. Serving as screenwriters, Rashida Jones and Will McCormack turn the script into a showcase of writerly wit; Seth Rogen supplies practiced bravado, and Wilde, quite the overachiever, reminds us of her comedic timing. Yet the film never quite resolves into lived experience and its flirtation with group sex, polyamory, or any deviation from monogamy amounts to little more than a suggestion quickly withdrawn.

Taken alongside David Wain’s return to feature filmmaking, Gail Daughtry and the Celebrity Sex Pass, which is still tethered to an early-2000s mode of domesticated farce, the festival’s treatment of sex skewed cautious. Georgia Bernstein’s Night Nurse, which premiered in the NEXT section, offered a partial reprieve. The quasi-erotic thriller opens with a young woman slowly coiling a telephone cord as she solicits a grandfather's help, an image calibrated for discomfort. The film drifts toward abstraction by the end, but at least flirts with risk, a boldness absent elsewhere in the program.

Documentaries remain Sundance’s strongest suit and this year offered a small cluster preoccupied with technology. Public Access takes a generously scaled look at Manhattan Cable Television, the anarchic public-access ecosystem that once beamed freakish, amateur, and occasionally inspired programming directly into American living rooms. Joybubbles, by contrast, narrows its focus to a single, quietly extraordinary figure: Joe Engressia, a “phone phreak” whose perfect pitch allowed him to whistle into landlines and place long-distance calls for free. Crucially, the film situates Engressia within a broader cultural moment without inflating his importance or forcing grand conclusions. He is, for instance, an original hacker. The archival material, much of it animations seemingly from early telephone company commercials, is disarmingly charming, its period cuteness mirrored by the film’s gently plaintive score, which echoes the childlike sensibility of Engressia himself, who later renamed himself Joybubbles.

That same tweeness curdles in The AI Doc: Or How I Became an Apocaloptimist from Charlie Tyrell and Daniel Rohrer. The latter’s hand-drawn illustrations and collage-heavy aesthetic feel wan and faintly infantilizing, a visual strategy meant to coddle us amid the film’s stated anxieties about artificial intelligence. Framed as a familial PSA—expecting a child, Rohrer and his wife are wondering aloud about the ethics of bringing a life into an AI-shaped future—the film is not overtly apologetic toward the technology, but it is conspicuously gentle. Its gaze remains forward-facing and solution-oriented, leaning heavily on interviews from AI’s own architects (Sam Altman, Dario Amodei; no Elon Musk, though he said he would appear) while sidestepping the more uncomfortable histories and skeevy power structures underpinning Silicon Valley.

For that, you’ll need to watch Ghost in the Machine by Valerie Veatch, which makes those histories the explicit subject of her intellectually dense, rigorously argued documentary. Veatch traces the obsession with optimization and the quantification of intelligence back to racist eugenic theories, positioning AI not as an inevitable tool, but as the continuation of longstanding efforts by white men in technology to rank, exclude, and declassify certain populations. The film features a wide range of interviewees—linguists, philosophers, and academics, named and cited repeatedly—who demand sustained attention. The title captions/text descriptions appended to the linguists, philosophers, and academics linger on the screen, while those in The AI Doc disappear instantaneously. One of Veatch’s most bracing assertions is also its simplest: “artificial intelligence” is, at bottom, a marketing term. Placed side by side, the contrast is stark. The AI Doc simplifies, anonymizing its experts by fading their bios almost as soon as they appear, and when it explains AI in terms of “inputs,” one wonders who, exactly, the film imagines its audience to be. Certainly not the younger viewers who could likely articulate the mechanics more fluently themselves. It ends in tidy takeaways: self-optimization and adaptation, call your congressman. At the Q&A following Ghost in the Machine, one of the film’s subjects urged tech workers to unionize in order to hold bosses accountable, emphasizing solidarity over individual action.

I gambled one last time with the deities of independent cinema and fulfilled my duty as a New Yorker, venturing out to watch John Turturro, Steve Buscemi, and Giancarlo Esposito inhabit a thief, a fence, and a detective, respectively, with rueful finality in The Only Living Pickpocket in New York. The moment James Murphy started to mourn the city in “New York, I Love You But You’re Bringing Me Down” and the rodent-grey city materialized on screen, I knew something unusually attuned was afoot—or maybe, after a week of supermarket tacos and Australian pastries, I was simply grateful to be transported back somewhere I knew through a movie whose plot points are traceable by subway stops. Once the story is set in motion, after Turturro’s character unwittingly swindles a young mobster (Will Price), the crime thriller becomes, essentially, a schlep, as he rides the four-train from the Bronx to Chinatown, doubling back, before venturing to the suburban heart of Forest Hills. Rarely does this kind of film allow its protagonist to navigate the city by public transit while racing against a ticking clock. Director Noah Segan opts for a laconic tenor, fashioning the film as a plaintive appeal to the past. This is a movie from another time, in form and scale and spirit: one of those stories for adults made with moderate budget and care, but one that also features people and places who are themselves an endangered breed. A pickpocket on one last job. A city overtaken by legal but soulless dispensaries… Perhaps, not unlike a festival nearing its own threshold.

Once I left Park City, my duties did not end. I stayed awake as long as I could, cramming in more viewings from the festival’s online press library. Like the East River’s lapping waves in the final images of Segan’s film, I carry on, screen flickering, in search of the stories and art that will last.

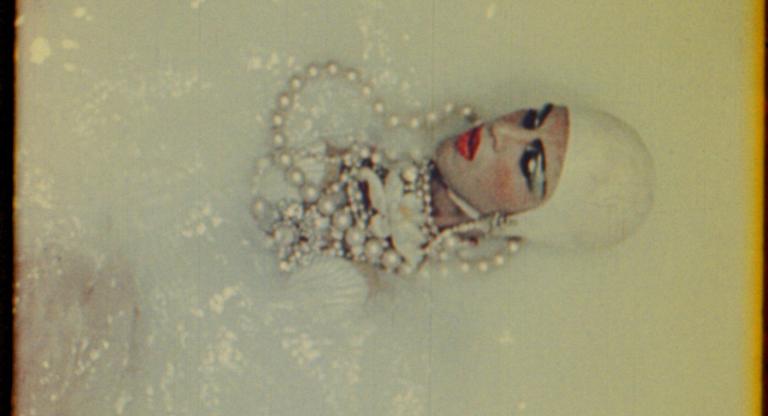

Photo at top by Lauren Hartmann courtesy of the Sundance Institute