Harold Lloyd might forever remain the slightly maligned third peg in the golden triangle of silent slapstick cinema, overshadowed by pantheonized clowns Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton even if he was arguably more popular in his day. For devotees of the genre he remains the quintessential figure. Lloyd’s films never had Chaplin’s rich character work and deep sense of pathos nor Keaton’s admirable technical ingenuity and sardonic cool, but he could work a gag like no other and excelled through sheer craftsmanship. “Each new floor is like a new stanza in a poem,” wrote James Agee about the iconic clock-scaling climax to Lloyd’s Safety Last (1923), speaking to the actor’s ability to string together lengthy sequences of loosely related funny business without ever missing a beat or failing to impress with sheer resourcefulness.

In few films in the Lloyd oeuvre is this more apparent than in Ted Wilde’s Speedy (1928). If the regular rhythm and static structure of Lloyd’s 12-floor climb in Safety Last is akin to a sonnet, Speedy is pure free verse, a robust portrait of 1920s New York in a series of wildly discursive gags and adventures. Filmed largely on location across a variety of iconic New York locales, Speedy is simultaneously a breathtaking city symphony and a slapstick masterpiece. The plot might concern Lloyd’s character, Harold “Speedy” Swift, helping his flame’s antiquated horse-drawn trolley business from getting screwed over by greedy rail tycoons; but this is little more than an excuse to follow Lloyd across the city. From a fight for a seat on the subway to a mad-cap taxi ride from the Old Hebrew Orphan Asylum to Yankee Stadium with none other than Babe Ruth in tow, Speedy is an exquisite merger of Lloyd’s comedy with New York’s rich urban character.

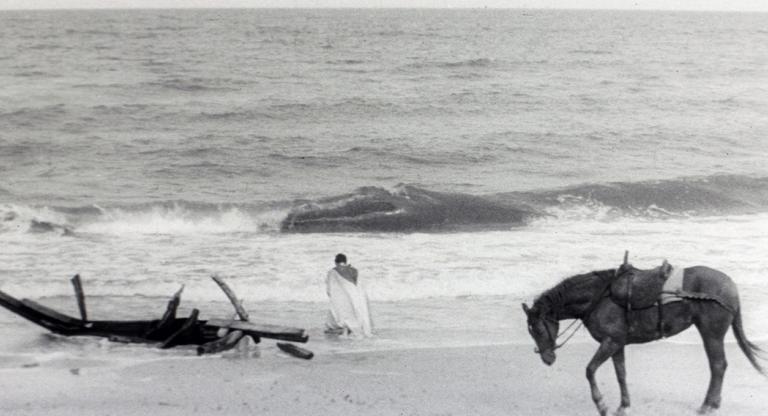

This reaches its apex in the film’s lengthy, show-stopping Coney Island sequence. Fired from his job and nearly broke, Lloyd takes his girlfriend to the beach and the result is a set piece that mixes documentary views of working-class leisure with a never-ending stream of comic non-sequiturs to pure delight. One string of gags finds Lloyd accidentally dropping a crab into his back pocket. As he walks around inadvertently popping balloons and pinching bottoms, the focus is as much on the environment as it is on Lloyd’s comedy, with each joke pushing him into new, colorful settings.

Chaplin may thrive in close-up and Keaton in long-shot, but this sequence proves Lloyd as the comic master of the middle distance, seamlessly merging into and out of the crowd as he sees fit in a true embodiment of the everyman. Such is suitable for Lloyd’s archetype as the relentless social striver, in a perpetual mad dash to beat the crowd and become an American success story through sheer ingenuity. This character would find its dark side in King Vidor’s The Crowd (also 1928), which shows the inevitable downsides of relentless personal ambition. Released the same year and both featuring a knockout Coney Island sequence, the two films are complements to each other, with Speedy providing the upbeat, Horatio Alger–esque ying to The Crowd’s downwardly mobile, melancholic yang. The two films would make a hell of a double bill, dispelling the myth of the American dream on one hand, while, on the other, reminding one of the spiritual uplift that makes it so intoxicating in the first place.

Speedy screens Saturday at the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum, with live piano accompaniment by Frederick Hodges, preceded by three shorts.

Previously:

Speedy screens this afternoon, May 27, on 35mm at Film Forum with a live piano accompaniment by Steve Sterner. It is part of the series “The City: Real and Imagined.”