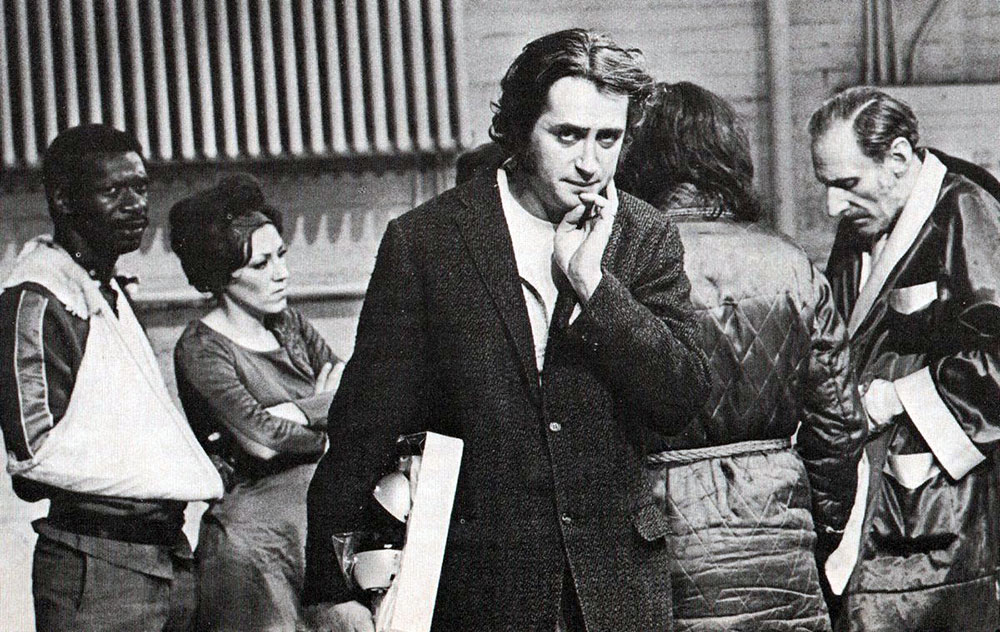

Robert Downey Sr.’s early films typically sprawl from one-line, high-concept premises that a more disciplined artist might have polished into coherent works full of grand statements. Instead, Downey’s promiscuous imagination could seldom remain faithful to his own promising conceits, such as Christ resurrected in the American West (Greaser’s Palace, 1972), the token Black executive taking over an ad agency (Putney Swope, 1969), and human actors playing dogs (Pound, 1970). He forswore craftsmanship in order to follow loose threads to dead ends, unleashing an ecstatic fart on the American self-image of respectability. This week, Anthology Film Archives’s own 35mm preservations of Downey’s first three features (discounting the work-for-hire softcore parody The Sweet Smell of Sex, 1965) are back onscreen alongside a new digital restoration of the better known Putney Swope, his sole commercial hit.

Warhol superstar Taylor Mead plays Sandy Studsbury, the President of the “United Status” in Downey’s debut, Babo 73 (1964). A graduate of Millard Fillmore University’s Hotel Management Program, President Studsbury stumbles googly-eyed around Washington and New York like a dandy drunk on champagne while fending off entreaties from his three-man cabinet to “kick the red Siamese out of the United Stagnations.” Most scenes feature Mead and one or two other actors performing Downey’s absurdist dialogue in secluded public places (cemeteries, beaches, parks), surely the result of the production’s low budget and aversion to permits. The jokes range from avuncular puns to multilayered satire of the military-industrial complex. When a cabinet member fires a gun toward an unseen target, Downey puts a baby’s anguished cry on the soundtrack before another man pops into the frame and asks, “Was that a Black Muslim?” Downey also makes hay out of the incredibly simple, yet hilarious, idea of the duly elected leader of the free world in the undignified act of running. Today, the film’s whirlwind of high and low gags would be at home on Adult Swim, while its shrugging attitude toward verisimilitude can be found all over Tiktok.

Chafed Elbows (1966), captures Oedipal neuroses in still photos and musical numbers, beginning with its main character relaying the story of the time he gave birth to 189 one-dollar bills after being diagnosed with a “devious septum.” While his father is at work, Walter (George Morgan) sleeps with his mother underneath a framed photo of LBJ throwing a Nazi salute. Like a twitchy Ken Burns avant la lettre, Downey zooms, spins, and crops his stills to match the febrile intensity of the script. When not confessing his anxieties about impregnating his mother to a shrink, Walter dies and ascends to heaven, fronts a pop band, is bought and sold as a piece of conceptual art, and kills a cop for talking too much. Tightening the production’s Oedipal knot, everyone one of the film’s female roles, from Walter’s mother to the topless “sock sniffer” who solicits him in a church, are played by Downey’s wife, Elsie, an arrangement as resourceful as it is surreal.

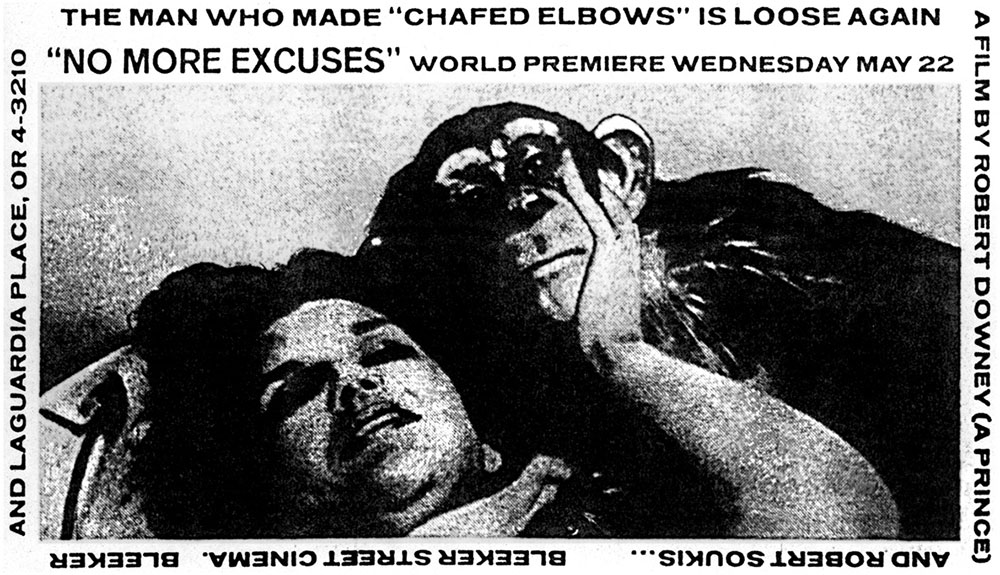

Downey recut five short films into No More Excuses (1968), which—despite the varied provenance of its material—somehow offers the best synthesis of his preoccupations, mainly sex and politics. (What else is there?) The strands include a Union Army soldier (played by Downey himself) transported to present-day Manhattan, a reenactment of the assassination of President Andrew Garfield, real interviews with men and women at uptown singles bars, and a deadpan diatribe by a man opposed to animal nudity. It’s hard to describe Downey’s work without resorting to lists because for long stretches the films resemble an anarchic parade of “and then . . . and then . . . ” Taken together, the film’s five constituents present an instantly recognizable portrait of a mid-’60s US obsessed with Presidential assassination, curious about fringe social movements, and unnerved by an expanding sexual permissiveness.

Formally, Downey matched the hallowed optimism of his era while the content of his work sneered at a country freefalling into endless war and corruption. “I don’t like any of them. To me they’re not funny,” he would later say of these early films. But they are deeply funny, as well as prescient about the hollowing out of American democracy.

“Robert Downey: A Prince (1936–2021)” runs through May 1 at Anthology Film Archives.