David Schwartz has spent nearly four decades as one of New York City’s most dedicated and reliable repertory film programmers. His tenure at the Museum of the Moving Image cemented his legacy, earning him a Career Achievement Award from the New York Film Critics Circle in 2019. His writing has appeared in Screen Slate, Reverse Shot, Filmmaker Magazine, Notebook, and Film Comment. He also edited David Cronenberg: Interviews, and has taught film history at Purchase College and New York University. Plus, he’s one of the nicest guys you’ll ever meet.

“A Theater Near You,” Schwartz’s Carte Blanche series at MoMA, is a tribute to 17 venues—seven historical and 10 in current operation—organized to showcase the breadth and diversity of New York City film programming from the 1930s to the present. The program spotlights the visionary curators whose passions, originality, and tenacity built iconic institutions that have transformed New York City into the Mecca of cinephilia.

I spoke with David about “A Theater Near You,” which opens today and runs through July 11. An edited version of our conversation follows.

Joseph A. Berger: I’d love to hear about your early experiences in filmgoing.

David Schwartz: I grew up in Huntington, New York, seeing movies at the Cinema Arts Centre. One day, I went into the city with a friend to see a double feature of Persona [1966] and 3 Women [1977] at the Art Theatre [now NYU’s Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Film Center]. The experience of watching those movies was transformative. Seeing Persona—largely about the medium of film—I was just blown away.

JB: And you moved to the city and went to Columbia University for a year?

DS: Yes, when Andrew Sarris was teaching there. His “Intro to Film History” course basically went from Birth of a Nation [1915] to Breathless [1960]. But the main thing that really got me on the track and led to my career was spending my entire freshman year attending repertory theaters. I had caught the bug for film; I worked out my schedule so that every day I could run from the Thalia to the Carnegie Hall Cinema to MoMA, then down to the Bleecker Street Cinema and The Public Theater. That one year really cemented my love of film. I was obsessed.

JB: That’s the case for so many of us who come to New York at a young age specifically to watch movies. There’s no other city in the world like it, where we have dozens of different options every single day. Where did life take you after your year of running around town haunting movie houses?

DS: I transferred to Purchase and eventually got a filmmaking degree. I was in the same senior class as Hal Hartley. But I was mostly interested in programming. A friend of mine and I hosted a screening of The Graduate [1967]. We commandeered the school auditorium, rented a 16mm print, got a keg of beer, and charged people $1. They would get a movie ticket and a beer. We made $400 for that single screening.

JB: That’s good by today’s standards!

DS: [Laughs] Yeah, it was a high per-screen average. You know, these were the halcyon days of the college film program because it was before VHS. Purchase, a relatively small art school, had three different film programs going on. There was a popular series, an auteurist series, and the program I curated, called the “International Cinema Series,” with a wide range of art-house films from around the world, like [Rainer Werner] Fassbinder and [Ousmane] Sembène. And I would throw in the occasional American film, like a Jerry Lewis or Blake Edwards or Howard Hawks title.

I was fortunate to have Tom Gunning as my teacher at Purchase. I took an avant-garde class with him that was very formative. My early interest in programming was really focused on experimental film. I knew that I wasn’t going to wind up making films, but I would somehow become a programmer.

JB: Let’s talk about your start at the Museum of the Moving Image.

DS: I made a student film, actually a pretty good documentary called Deadhead [1985], about a teenage suicide pact. It was in the Student Academy Award Competition and finished second in the region. Being in that competition got me on a mailing list of internships; one opened up at what was then called the American Museum of the Moving Image. I got an internship in film programming, a 10-month, full-time position that paid $10,000, funded by the National Endowment for the Arts. The great film historian Richard Koszarski was the main programmer at the time, and the woman who hired me, JoAnn Hanley, specialized in video art and new media, a focus of mine then.

That internship ultimately led to a full-time job. When the building opened in 1988, I was a Program Assistant. My debut series was of first-person documentaries. I booked the first public screening of Ross McElwee’s Sherman’s March [1985]. At any rate, that led to a full-time job and I was at MoMI for 33 years.

JB: And what was your final role there exactly?

DS: My title kept changing, but within a few years, JoAnn left the museum. By 1991 or so, I had become the Coordinator of Film Programs. Then it became Head of Film and Video. This was before it was fashionable for everybody to be called a “curator.” Eventually, my title was Chief Curator for many years. But it’s a misused title. I think of myself as a programmer—and that's really the right word for it.

I left MoMI in 2018 and worked on various freelance programming projects at venues like Metrograph and the Kennedy Center’s new building, The REACH. After about a year of that, the opportunity came up to work with Netflix when it was reopening the Paris Theater. I started that job about three weeks before the pandemic. I was there until April 2023, essentially setting up the theater: we renovated the building, built the website, and launched the programs.

It was interesting to work for a huge company. I learned a lot. I’m glad I did it, but now I can do a variety of things, right? A lot of writing and freelance work. I’m programming the Barrymore Film Center, a new theater in Fort Lee. I also have a film club in Westchester and programmed three different Jewish film festivals this year. This MoMA program is very exciting for me. I’ve never programmed there before.

JB: How did this come about? Did Raj [Rajendra Roy, The Celeste Bartos Chief Curator of Film at MoMA] come to you? Or did you go to him with this pitch?

DS: Raj floated the idea of me doing a Carte Blanche program—extremely generous. I’m thrilled. MoMA’s Carte Blanche series has been programmed by people like Amy Taubin and Stephen Sondheim. It’s very meaningful to be among these guest programmers. But the question was, “What would it be?” And Raj gave me free rein to come up with an idea.

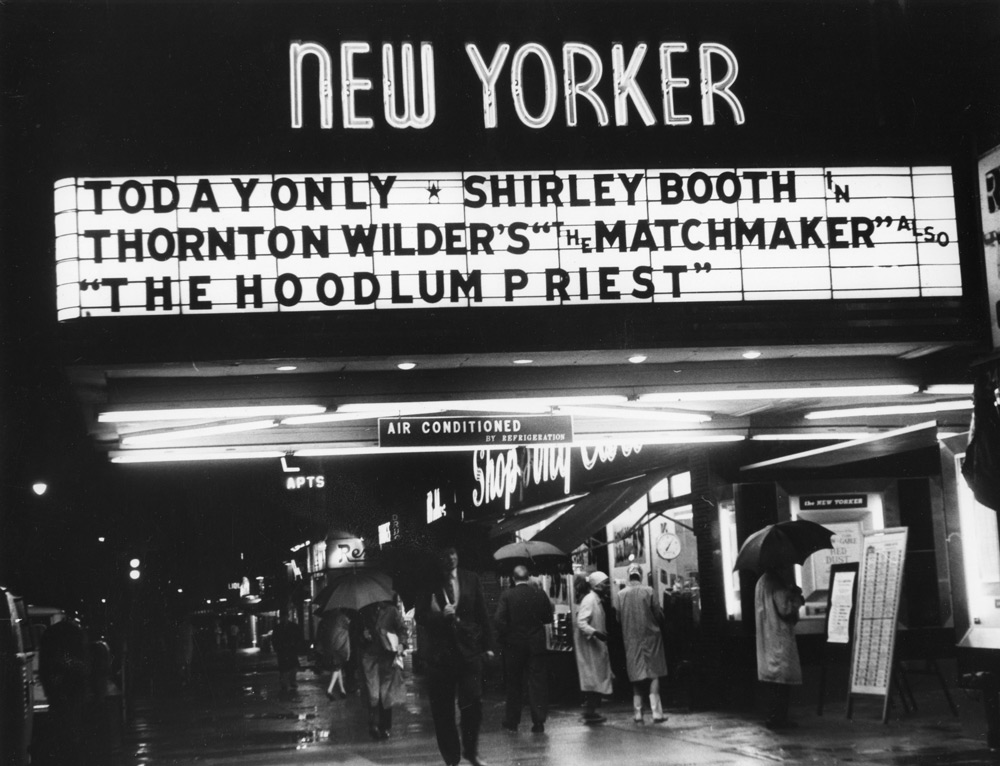

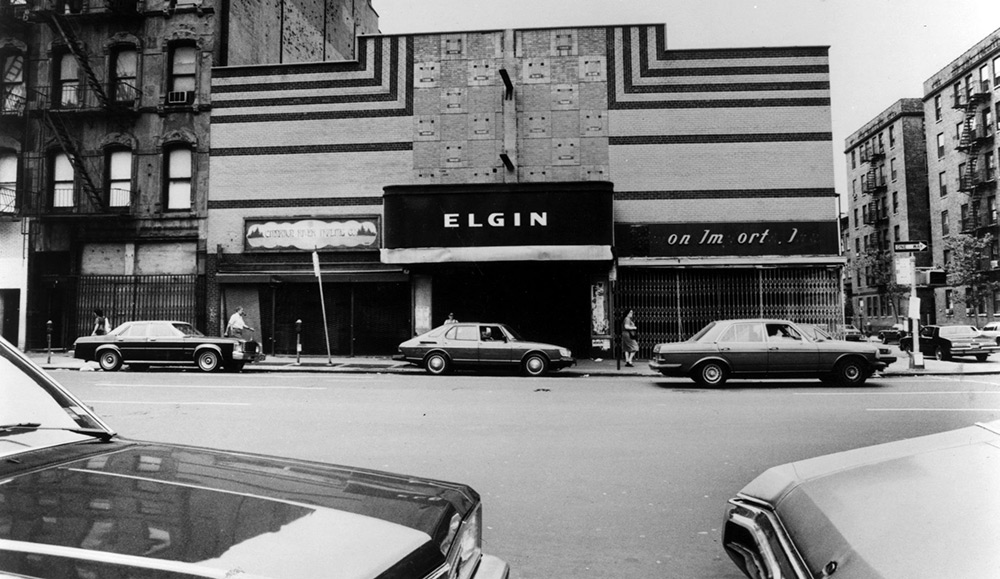

My main thought was that I wanted to create a series that was about programming in some way. And “Carte Blanche” implies that it’s going to be a very personal series. So, I thought I’d do a series about the theaters that influenced me as a New York filmgoer. I made a list of the venues that I went to all the time. But that felt a little narrow, as my heyday of repertory filmgoing was from around 1979 to 1990. We landed on the idea of looking at the entire New York scene, not only going back to early cinemas like the Thalia, the New Yorker, and the Elgin, but right up to the present day, including Maysles Documentary Center and Light Industry. And then we finally added Spectacle and the Charles.

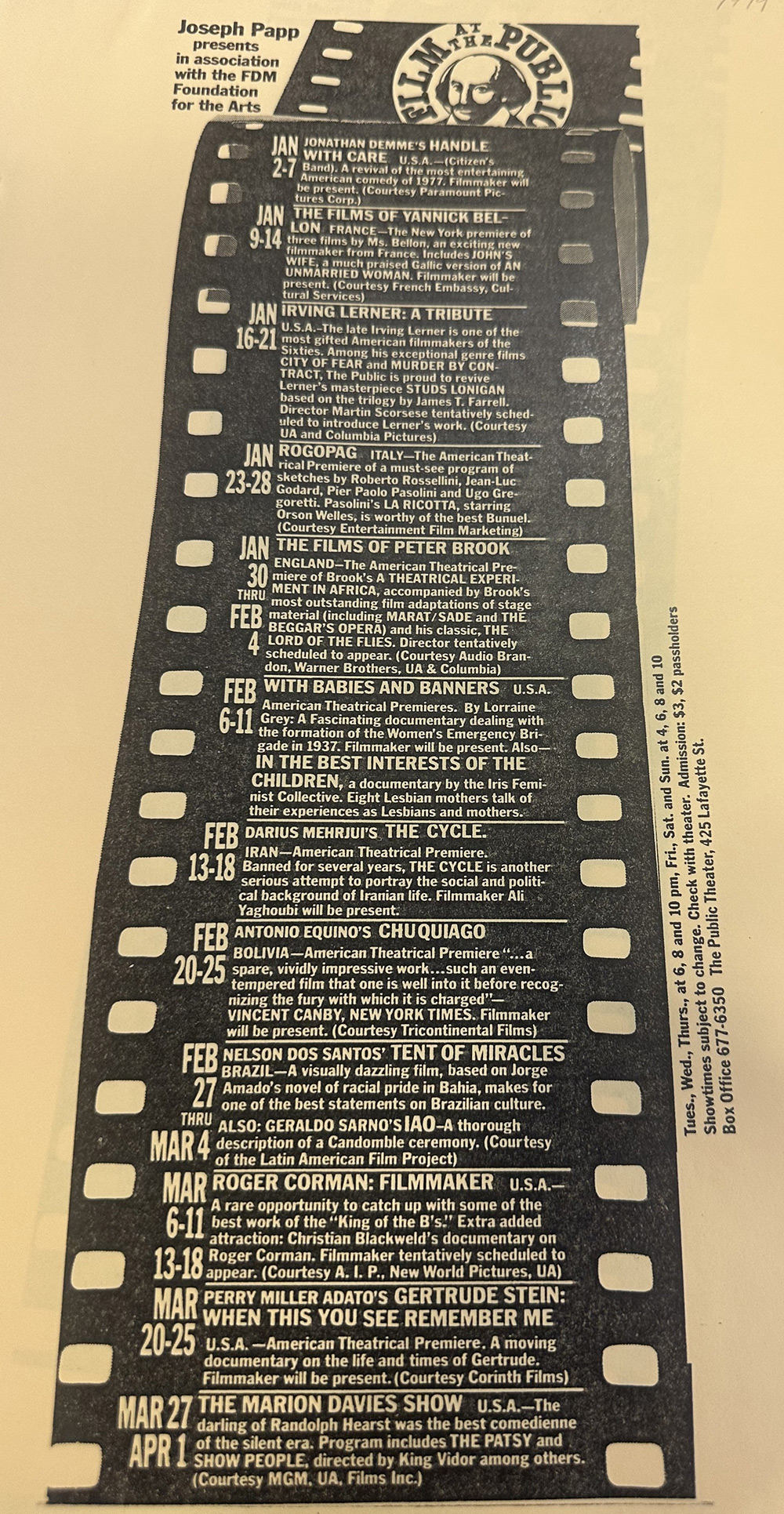

One of the things underlying this whole program is how important certain programmers can be. Richard Schwarz of the Thalia and Dan Talbot of the New Yorker are well-known examples, but Fabiano Canosa, who programmed the Public Theater—I loved his programming. When there’s a great programmer, you trust them and know that their choices will always be interesting. I knew whatever was playing at the Public Theater would be worth seeing.

And there are theaters I’m including in the series that I never went to… I never went to the Charles; the New Yorker was a little before my time, and, of course, I never went to Cinema 16. Cinema 16 is a bit of a cheat because it wasn’t one specific theater but rather a roving program playing in many different venues.

JB: That’s a great segue. I’d love to discuss a few of the surprises on your list here, programs and venues that I know very little about. I think, except for MoMA, Cinema 16 is the earliest venue on your list?

DS: Correct, the Museum of Modern Art began its film program in 1935, founded by the British-American critic and collector Iris Barry. She was quite radical. One of her favorite films that she programmed early on was I’m No Angel [1933], starring Mae West. Iris loved it, and it was a surprising thing for MoMA to screen. She was really making a statement that these early American films were worth saving and looking at.

Cinema 16 was founded in 1947 by Amos Vogel. I knew Amos mainly through his book, Film as a Subversive Art, which is one of the greatest film books ever. It’s a thematic book about films that break taboos and are revolutionary in specific ways, whether through subject or form. They’re sexually explicit, they’re violent, they’re transgressive—and it became a guidebook for me. I would check off films in the index when I saw them. So, of course, I read about Cinema 16.

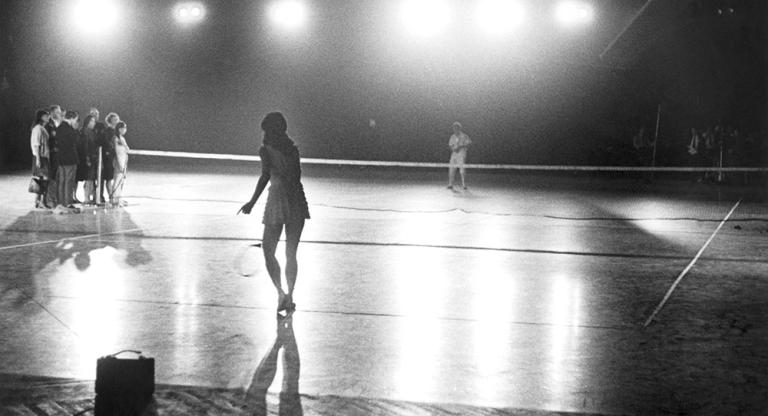

There weren’t other theaters like that at the time. Cinema 16’s first venue was the 1,600-seat Fashion Industries Auditorium [then called the Central Needle Trades Auditorium]. He put together weekly shows that would constantly sell out and were extremely interesting: a mix of experimental features, international titles that hadn’t premiered in the U.S., documentaries, industrials, cartoons. So eclectic! It was membership-based, one of the most successful ever, with over 7,000 members.

I had a sense of how important Amos Vogel was as a programmer. One of my favorite programs in this series is where he combines Fireworks [1947], Vampyr [1932], and Blood of the Beasts [1949]. Fireworks was a discovery of Vogel’s, an avant-garde short made by a 20-year-old Kenneth Anger, a very bold film at the time. Vogel programmed it with Carl Dreyer’s film from the early ‘30s and Blood of the Beasts, Franju’s poetic documentary short, much of which was shot in a slaughterhouse. These three films—who would think of putting these together? Beautiful.

JB: I love that you’re re-creating exact programs by these mythical master curators. It’s precisely the kind of thing that gets the nerdy historian in me so excited.

DS: I’ll give you another great example. Dan Talbot loved to come up with weird combinations of movies, so when he opened the New Yorker Theater in 1960, the debut program was the one that I’m featuring: Pull My Daisy [1959] and The Magnificent Ambersons [1942]—a loosey-goosey, avant-beatnik film with improvised narration by Jack Kerouac, paired with a Welles… That’s a wild idea. It’s like what Martin Scorsese said about double features: you don’t want to pair two films that are the same, you want two very different films. So, that program is a Dan Talbot classic. He loved doing that. Once, he programmed Luis Buñuel’s Él [1953] with Fritz Lang’s M [1931] because he thought that was funny.

BERGER: So, is it fair to say then that this series is more of an homage to specific programmers than actual venues? When I saw the Film Forum double feature, I thought, “Oh, okay”—Sullivan’s Travels [1941], a great Bruce Goldstein classic with Sans Soleil [1983], which Karen Cooper premiered.

DS: Yes, that’s exactly it. Bruce picked Sullivan’s Travels immediately. It was one of the titles in the double feature he screened on the opening day of Film Forum’s Houston Street location [the other: The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, 1944]. And the joke here: Bruce’s pick is an entertaining, playful comedy paired with the Marker film chosen by Karen, who’s famous for screening documentaries and more serious films. Karen is proud that she premiered Sans Soleil. It received a very negative review from Vincent Canby, who was likely having a bad day, in a grumpy mood, and panned the film. I’m looking forward to hearing what she has to say in her introduction. I mean—and you, Joe, know Film Forum more than just about anybody—here you have these two larger-than-life personalities…

JB: Who, I’ll say, are so different. The wonderful gentleman’s agreement between the two of them was that they worked totally independently of one another, but trusted each other completely. I think that made for a very unique cinema.

DS: But to get back to what you’re asking, it’s a great question: is it about the venue or the programmer? The real answer for me is that the great venues are the ones where you can feel the personality of the programmer. For me, one of the most important programmers on this list is Fabiano Canosa, who programmed at The Public Theater.

JB: Let’s talk about The Public’s cinema history, because I know almost nothing about it.

DS: When Anthology Film Archives first opened in 1970, it spent four years in the Little Theater space at Joseph Papp’s The Public Theater. That was where Jonas Mekas set up his famous Invisible Cinema, with a wall built around each seat. The viewer was completely isolated—a wild, purist approach. In 1978, Papp reopened the screening room to show films that couldn’t find a proper outlet to the general public, and he hired Fabiano Canosa.

JB: Tell me more about Fabiano.

DS: Fabiano was from Brazil and had lived in Paris for a long time, studying and working at the Cinemathèque Française with Henri Langlois, who’s really the godfather of all of this. Fabiano had a very eclectic taste. He loved Portuguese films and Manoel de Oliveira, so one week you’d see Doomed Love [1978], then the next week he’d run a Larry Cohen retrospective. He premiered Bertolucci’s first film, La commare secca [1962], so that’s what I’m showing at MoMA.

At the time he was programming, there weren’t as many venues as there are now. The commercial repertory theaters were starting to close down, and the nonprofit theaters were emerging, but Lincoln Center hadn’t started year-round programming yet, and BAM Cinématek didn’t open until 1999. So it wasn’t this crowded scene—he had freedom there to show what he wanted. It was also a small theater—90 seats—so there wasn’t a lot of pressure. He was at the height of his programming right when I was getting started, so he was very important to me. He’s a charismatic and interesting person, and he’s still around. He’ll introduce the Bertolucci on June 19th.

JB: Another surprising choice here is the Charles Theatre on Avenue B, which had a very short life.

DS: A short life, but an important one. Jim Hoberman wrote about the glory days of the Charles in an article from American Film [“The Short Happy Life of the Charles,” 1982]; he considered it a “landmark in the creation of the American counterculture.” Dan Talbot opened the Charles in 1961, envisioning it as an East Village version of the New Yorker. He hired two very young men, Walter Langsford and Edwin Stein, Jr., to manage and program the venue. In its one year in operation, they transformed the Charles into a great showcase for American avant-garde films: they programmed Shirley Clarke’s first retrospective, premiered Stan Brakhage’s first featurette [Anticipation of the Night, 1958], and screened Brian de Palma’s first two shorts [1960’s Icarus and 1961’s 660124: The Story of an IBM Card]. The Flower Thief [1960], a lesser-known early film by Ron Rice, is wonderful. It was given a three-week run at the Charles, which is unheard of for a movie of its kind.

JB: I imagine that a challenging aspect of putting this series together was having to exclude some great venues.

DS: Yeah, the danger of the series is, “What theaters am I leaving out?” And then, for each theater I chose, like, “Why did I pick these films and not those?” I’m sure people will question my choices, but to me, this mix makes sense.

I’m glad we’re including L’Alliance New York; I wanted to draw attention to its extensive history. It’s great that Jake Perlin is there now; I’m focusing on his programming, as well as that of Delphine Selles-Alvarez, his predecessor, who continues to program animation for the organization.

One of my very favorite programmers right now is Jed Rapfogel at Anthology Film Archives. He is brilliant. He puts together these amazing thematic programs. I’m not sure if he’s done this exact program at Anthology before, but he selected a collection of films without images and films just made of words. It’s called “Imageless Films and Motion(Less) Pictures,” and it’s 100% a Jed Rapfogel program. I couldn’t ever have come up with it, and that’s exactly what I wanted. So, in a way, one of the things I’m doing in this series is curating the curators. Sure—it makes my work easier, but it’s also making a statement.

JB: I love your inclusion of newer venues like Spectacle and Light Industry. I mean—Taiga [1992], the Ottinger film? Eight hours of Ottinger! I love her movies, and I’ve never seen this, so I’m very excited—what a great choice!

DS: That is totally Ed Halter and Thomas Beard. And you know, if they had their way, the “American Serial: 1914-1944” marathon they put together would have been 12 hours long. Unfortunately, it could only be five hours.

JB: Oh, wow… So they’re getting a five-hour and an eight-hour program! Ha!

DS: Well, they don’t get repeat screenings! But I went to Raj and told him they wanted to do this. He said, “Yep!” He was very cool about it.

JB: Well, David, I commend you. This is such an inspired and beautiful way to honor not only the past, but especially our present-day programmers. I’ve always felt that “rising tides lift all ships.” I’ve never seen this community, this small world that we’re a part of, as competitive by any means. It’s so collegial. Everyone's various expertise and passions inspire everyone else’s. Your series really uplifts that tradition and reminds New Yorkers that we’re all in this together.

DS: In closing, I’ll say that’s such a big part of what this series is: it’s about the audience, all of us who are cinephiles, the people who love films and go to these theaters. And you, Joe, you’ve done great work, so it’s wonderful to hear that compliment from you. I really appreciate it. You know, I was lucky enough to make some kind of career out of programming, but really… I’m just a movie lover.

Special thanks to Lulu Fleming-Benite.

“A Theater Near You” runs June 12-July 11 at the Museum of Modern Art.