To watch psychoanalysis watching. Perwana Nazif and Hannah Zeavin make this possible within The Parapraxis Film Festival.

Cinema and psychoanalysis arrived together at the turn of the 20th century. 1895 witnessed both the Lumière brothers’ first public film screening and the publication of Freud’s Studies on Hysteria. Film theory has long looked to psychoanalysis for conceptual tools, but Parapraxis redirects attention to psychoanalysis’ own cinematic archive.

The selection of films demonstrates what it might mean to take that archive seriously as a record of cinema and psychoanalysis, co-implicated practices of seeing, recording, and meaning-making. Organized around clinical sites and pioneering figures, the program features films from the 1930s to the present, with a global perspective that emphasizes French institutional psychotherapy and postcolonial psychiatric practices. Parapraxis reveals how these two techniques and technologies are linked beyond their common origin, positioning them as mutually constitutive forms of projection and interpretation.

Nazif and Zeavin sidestep the familiar thematic overlaps between cinema and psychoanalysis, as in their shared operations (dreams, fantasy) and analogical affinities (filmmaker as analyst, montage as free association). Instead, the curators organize the program according to historical and methodological groupings. Almost every film approaches psychoanalysis vis-à-vis its subjects: analysts such as Freud and Fanon, and analysands from anonymous children to filmmakers themselves. This foregrounds a fundamentally humanistic portrait of cinema and psychoanalysis that, despite a mutual concern with interiority, have long been put in dialogue through more abstract frameworks.

Freud and Fanon bookend the festival and haunt it throughout. Fanon’s presence in the program’s final two days (Fanon’s Clinic; Remember to Play: Children, Psychiatry, and War) signals the mutual reinforcement between psychiatric and colonial othering: the colonized subject is pathologized, and the pathologized subject is colonized. Yet the program is united by a will to resist the othering impulse inherent to cinematic capture and psychoanalytic dynamics alike. Throughout Parapraxis, the estrangement of the other becomes the estrangement of the self. Psychoanalytic theory presupposes that we are fundamentally unknowable to ourselves, and these films contend for a shared encounter with our own opacity, and an individual encounter with that of the collective.

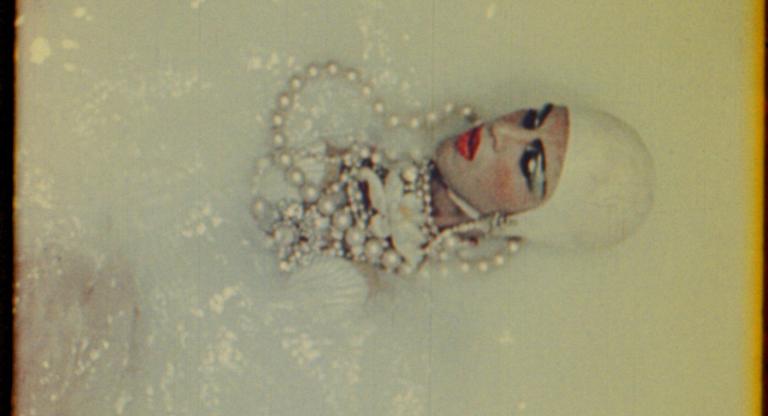

The Trieste films, presented within the Italian Democratic Psychiatry section of the festival, might best illuminate the potential extimacy produced by the dialogue. The series was created collaboratively between patients at Franco Basaglia’s revolutionary Psychiatric Hospital of Trieste and filmmaker Andrea Piccardo in the early 1970s. Basaglia, a key figure in deinstitutionalization efforts, transformed the hospital into a space of radical therapeutic experimentation. By connecting a camera to a television, Piccardo and his collective created a “potential visual circuit,” allowing patients to see themselves on screen in real time. The cybernetic structure disrupted the unidirectional logic of psychiatric observation, eliciting from patients a new “media-inflected language” and works of “pure cinema.”

Central to the arc of Parapraxis is the reimagining of institutional psychotherapy. The program’s second segment, Experiments in Film and the Clinic, centers Francesc Tosquelles’ wartime innovations at Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole. Tosquelles, a Catalan psychiatrist who fled Francoist Spain, reconceived Saint-Alban Hospital from a traditional asylum into a site of political and therapeutic refuge. Deligny, influenced by Tosquelles’ work and briefly connected to La Borde Clinic, eventually pursued an even more radical path, establishing non-hierarchical care networks for autistic children.

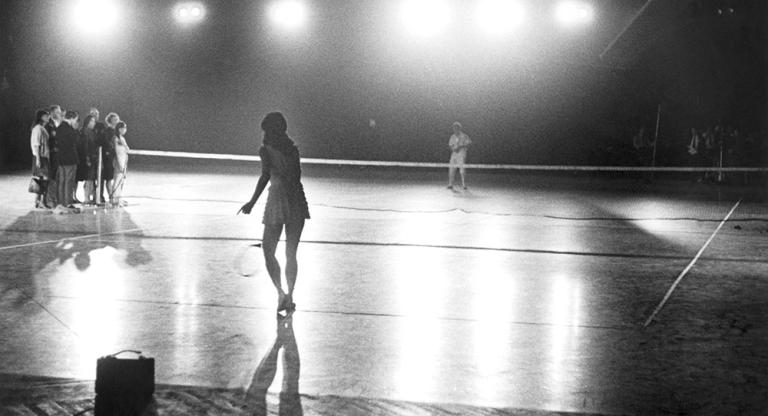

This philosophy of care informed Deligny and Renaud Victor’s 1975 Ce gamin, là (That Kid, There), featured in the festival’s Fernand Deligny: For Asylum segment. The film exemplifies what Deligny termed “camera-ing”: a film practice that aims to “say nothing,” “write nothing,” and “emit nothing.” The technique echoes the psychoanalytic fantasy of clinical neutrality (Freud’s ideal of the analyst’s “evenly hovering attention”). The work resists the cinematic-psychiatric impulse to position subjects as objects of analysis, instead privileging gestural sequences and poetic abstractions characteristic of slow cinema (as Deligny put it: “language disappeared as one may say of the sun”).

The impossibility of communicating “nothing” only underscores that the analyst, like the filmmaker, is fundamentally creative. They listen and frame, interpret and compose. Inverting Deligny’s principle of silence with an imperative to invent, Tosquelles’ psychiatric practice of déconniatrie, or “mess around-iatry,” embraces a form of therapeutic play where both patient and analyst mess around before arriving at “a little interpretation.” Deligny intuited that “saying nothing” is itself a form of invention, positing restraint and creation as complementary rather than competitive forces. Psychoanalysis is not a hard science, and that’s precisely what makes it both real and poetic—or, in a word, cinematic.

The Parapraxis Film Festival runs from September 19–25 at Light Industry.