“You had reached the point where one drink was too many and a hundred not enough.” Charles Jackson’s best-selling 1944 novel The Lost Weekend portrayed the inner life of dipsomaniac and would-be novelist Don Birnam. Screenwriter Charles Brackett, whose wife was a severe alcoholic, as was his close friend Dashiell Hammett, said Jackson’s study of a failed writer “had more sense of horror than any horror story I ever read.” The New York Times called the “stream-of-unconsciousness” psychodrama “the most compelling gift to the literature of addiction since De Quincey [author of Confessions of an Opium Eater].”

Following the sexually charged and chillingly satirical Double Indemnity (1944), Billy Wilder teamed up with Brackett to create the first major studio film to treat the topic of alcoholism in serious terms. Until then, drunks in movies were rarely more than comic relief. Ahead of Wilder’s production, the Allied Liquor Industries, a national trade organization, wrote to Paramount with concern that the film could hurt alcohol sales. As the critic James Agee joked in his review for The Nation, “I undershtand that liquor interesh: innerish intereshtsh are rather worried about thish film. Thash tough.”

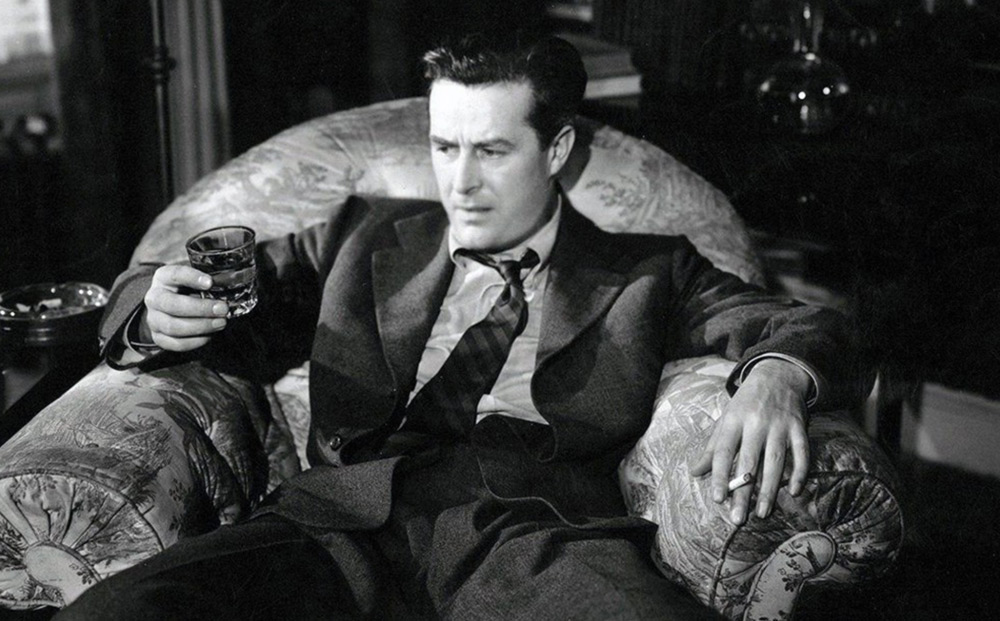

Wilder and Brackett were drawn to the self-referential thrill of writing a film about a tormented scribe whose drinking problem is, ironically, fueled by his failure to complete his autofiction about his drinking problem. As with his use of the likeable Fred MacMurray as a killer in Double Indemnity, Wilder smartly cast the charming Ray Milland as Birnam. According to Eric Monder in his excellent new Milland biography Dashing to the End, the actor almost demurred after reading the novel. “Beautifully written, but depressing and unrelieved. Damned interesting though, only it’s going to call for some pretty serious acting and I don’t know whether I’m equipped for it,” he told his wife, before she convinced him to take the part. Inhabiting Birman, Milland gave the performance of his career as a silver-tongued genius whose sharpest words are the ones he uses to excoriate himself and who feels unable to conquer his addiction. As Birnam says, “Once you’re on the merry-go-round, you got to ride it all the way.” Milland’s performance earned him both an Academy Award and a Cannes Best Actor Award.

With its minimal but essential use of New York location photography, The Lost Weekend has a neorealist flavor. But, the film’s true power does not come from any kind of documentary realism; instead, it arises from the almost dreamlike, subjective quality that permeates the movie, which is complete with hallucinations and shock images (including an unforgettable extreme close-up of Milland’s eyeball after a drunken blackout) that evoke contemporaneous avant-gardists such as Maya Deren and Kenneth Anger. At its first preview, audiences laughed, perhaps uncomfortable with its rawness. Double Indemnity composer Miklós Rósza was brought on to salvage the film, and he created an effectively moody new score, using eerie theremin music to express Birnam’s interior state.

The Lost Weekend swept the Oscars, winning five top awards (Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Actor). Even the liquor industry got behind it and Seagrams ran an ad praising what it considered to be its message. It read: “Paramount has succeeded in burning into the hearts and minds of all who see this vivid screen story our own long-held and oft-published belief that… some men should not drink!, which might well have been the name of this great picture instead of The Lost Weekend.” Thankfully though, the movie does not play as a social problem drama with a message, but as a gripping portrait of an artist’s struggle to conquer self-loathing.

The Lost Weekend screens this evening, December 26, through Thursday, January 1, at Film Forum on 35mm. Monder will be in conversation with Molly Haskell following tonight’s screening.