On a recent Sunday afternoon I met with Jonas Mekas — poet, filmmaker, and artistic director of Anthology Film Archives—at the apartment where he lives and works, on a quiet street in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn. Though he was busy with his work and with preparations for a benefit and auction to raise funds for the construction of a new cafe and library at Anthology, he generously made time for us to talk around a small wooden table in the presence of his cats. Just before I turned off the recorder, Mekas began to tell me about a Chinese poet from the 8th or 9th-century who, he said, "wrote most of his poetry not on paper but on walls, on anything, anywhere, on trees, on stones." I would like to use that image as a preface for the conversation that follows:

On March 2nd Anthology Film Archives is holding a benefit and auction for it’s Heaven and Earth library and cafe at CAPITALE (at 130 Bowery), including a performance by Patti Smith. Tickets are available here.

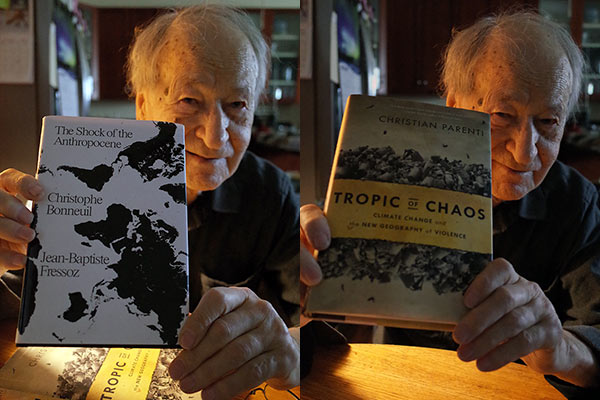

Instead of a new photo of himself, Mr. Mekas asked if he could recommend these books to everyone.

I thought a good place to start would be with some history.

I hate that.

You hate history!

Yeah, because everybody always wants to talk, “Oh, so how was Warhol? How was John Lennon?” They just want to talk about personalities, and they are not interested in what I'm doing now and about Anthology Film Archives—what’s important now. Then they finish the history and they give one paragraph, one sentence on what I am doing now. I would reverse it. I would give one sentence on the past. Because that has been covered and written about, and I am not interested in it. My whole work, what I’m doing, you know, the form of the diaristic cinema is based on here and now, so that my interest is always in the moment, the present moment. And they always want to talk about the past. I’m only interested in the present moment, in what needs to be done now, and what I am doing now. That’s my life.

Then can we start with what’s happening in five days with the new president?

I’m totally disinterested in politics.

In politics...

Yes. I live outside of the political world. Because I have no control. Because all my interest is in cinema, and not even all of cinema. I’m not that much interested in narrative cinema. I’m more interested in non-narrative forms, because they are the most neglected, and they must be more brought into focus. The poetic cinema needs more visibility. You see, that’s what I am interested in. The politics—there are many people who know something more about it than me, and they will do whatever has to be done, whatever can be done.

Can I ask you then about what is happening now with poetic cinema—not so much the past? You were saying that we need to have more visibility for the poetic cinema.

The poetic cinema, yes.

Is there anything that you feel is lacking right now? Is it places for it to be seen?

It's still, I think, with the education system. The way it is now in America, with arts practically pushed out by sports and everything else, there is no education in the arts. So, only the public media—all the public media deal only with the commercial cinema, commercial forms and content—the television. The independents that are working in the smaller forms of cinema, more poetic forms of cinema, non narrative forms of cinema— they rely mostly on museums, on some galleries here and there, and it's a constant effort to persuade them to keep film programs part of their activities.

But do you feel like they need to be organizing outside of those places? Do you think it can be a healthy relationship, or do you think it’s a bad—

No, I think the lack of general education that cinema is not only the public cinema, the melodramas produced in Hollywood, let's say, or in other countries. But, the same as literature— literature is not just novelistic writing or even short stories, but there is also poetry. So, there is a lack of, I think, of demand in a way that the people don't realize that that kind of cinema exists. And we should see it because there is a content which, I think, humanity needs in order to become more subtle. We are surrounded with banality! And much of the public cinema and what we see on television, it's part of that banality, and we need more subtle kinds of feelings to support that area of art. There are some places where some of these films are available. And, of course, Anthology Film Archives is dedicated primarily to that, to the film avant-garde, to the independents. Though we are very open to all of the special classics of cinema, to all of the narrative forms. To us cinema is one big tree with many branches. And we represent, we want to show, and we show examples from all of those branches

With your work at Anthology does it feel more difficult now to find new work to show that you really think is expressing that poetic cinema?

Not that much good work, but there is a lot of good work. Much of it these days is produced, really, on internet. It's not necessarily that you find it in cinemas, in the movie houses. Some of it is on internet. The dissemination systems are changing—dissemination of the moving images.

Do you think that dissemination can be a problem, when it becomes so democratized?

No. No problem. The easier it is to distribute, to make it available, the better. It used to be you had to make a film—even if you make it on 16mm—you still have to make a print to send it. Then they screen it two or three times and they destroy it or they scratch it. And you send a print, it takes one week to get there, one week to come back. Within five minutes your friends can see what you just made five minutes ago. So it's very good that the new dissemination channels are available. It's terrific.

But are people talking about it together?

Some are talking. There is exchange between friends. But, of course there is—even if it's just on film or on video and shown in theaters it's the same. You cannot see everything that is being made. If you go to 1960 I could say that I had seen every avant-garde, every experimental, independent film made in America or anywhere else. I could say that because it was true. By 1970 that was already impossible. The change that took place between 1955 and '65 is so immense, because by 1970 or '75 there was already the American Native Indian Cinema, the movement to create a Black Cinema, there was a Gay Cinema, there was Lesbian Cinema, American Asian Cinema—all kinds of cinemas. And you have to be part of it to really know what was happening in that area. For one person it was already impossible to see. And I'm talking, let's say, about just United States. But what was happening in France or in London or in other countries? Today, with the digital and internet, it's totally impossible. So, it would not be realistic even to think that “Oh, we should somehow try to find out what is the best of what is made today.” No, you cannot do that anymore. Only time will show, same as in all the other arts. Much of it that is second rate, that does not have intensity, people don't care about it and it disappears. So, only what has some intensity or something special that people want to share among themselves is preserved for posterity. And that weeds out all the secondary materials, so that even if you don't see what is today produced, let's say, in India or Peru, I think in twenty, thirty, fifty years we will know what survived from that period, what remains.

I’m curious, how often do you go back and look through the footage that you have?

Occasionally I put on my website like a—actually, yesterday I put a piece on my website.

I saw it.

No, actually I taped it just now, but the subject is nearly from the Sixties. But, I pick up some pieces of material from earlier years and I put it on my website for various reasons.

That was the picture of Lenny Bruce. [On January 14, Mekas posted a video on his website in which he talks about a moment involving Barbara Rubin, Lenny Bruce, a headshot of Bruce, and a tube of pink lipstick that took place during the summer of 1964 when both Bruce and Mekas (along with Ken and Flo Jacobs) were defendants in their own, separate obscenity trials.]

And why I put it there, because somebody is making a film now on Barbara Rubin, and I asked him if he knows about that moment, that incident—what happened between Barbara and Lenny Bruce—and he said he did not know. So that gave me occasion to record that moment, that event. And I put it on because it brought my memories back. But I have so much material, and then I keep making more now, so it's not often that I go back. But, sometimes I collect, I go back. Someday I will have to go back because—I'm still finishing editing my unfinished film materials. I still have a lot of film, unedited film materials, which comes from before I went into digital. I have to finish that because film is fading and I have to do something with it right now. Then, after that, I will go to look at some of my earlier video footage.

When you made that change to video—obviously on the surface you can see there’s a change in the way that you were shooting.

Yes. Different content. Different tools make accessible new content, and then there is a new style and a new way of recording it. Because video permits you to go without any carrying. You don't have to carry any lights. You can go into any situation without disturbing people. And taping—it's not like with film where the cameras make noise. So that new areas of life, of content are opened to you.

But you're still using the same video camera, correct? You've been using the same camera for a long time.

No. No. I used a Sony until—

[Mekas stands up, walks over to his kitchen counter which is cluttered with papers, and picks up his gray Sony video camera.]

I am still using this Sony most of the time. But I'm now, also, I have in my pocket... I also use this is more recently.

[Mekas puts down his Sony, walks back, and reaches into the pocket of his jacket, which is hanging from a nearby chair. He pulls out a small Nikon “KeyMission” camera about the size of a Zippo lighter.]

And it shoots video?

Yeah. Good quality, good sound. So, that’s very far from 16mm technology.

From the Bolex.

Or Bolex, or even Sony. And why not? It’s like, you know...

[Mekas picks up a pen from the table and holds it up.]

Like the pen... Before I came I was reading some notes and short pieces that you had written, that were published recently [as Scrapbook of the Sixties: Writings 1954- 2010 ], and there was something—I think it was from 1983. It was on a conference called “The Media Arts in Transition” at the Walker Arts Center. You had written a dialogue between three people—A, B, C. But, when you take all three together, there was some sort of ambivalent feelings about technology and about the good that technology does. I think there was even one line where you said something like, “In times of technological advancement or progress, art takes a vacation”.

I am all for moving ahead. You cannot stop. Technology will keep moving ahead. But, I also have to say that the humanities are—those who use these new technologies are a little bit behind in their, let's say, understanding of the technology and lag behind in their sensibilities, in their moral, ethical maturity. I think that humanity is still more like a bad child, so that these new advanced technologies—a bad child can use it for very negative purposes. In short, humanity is not enough grown up yet to use these advanced technologies. Technology is a little bit ahead of humanity. So, humanity has to catch up. And that's where the danger at this point is. And that's, of course, where we talk about nuclear, you know, wars. Because humanity is not there. Technology is much more advanced than humanity. So, that's where we are. And that's where the danger is.

But I wonder what that means for cinema. In particular, the kinds of cinema that you're talking about.

Yes, cinema is the least, maybe, damaging part of that. And, actually, the communication part, the exchanging of ideas, the internet that you can have on every spot of the planet—everything can be accessed immediately—that's the good part of it. And I think that's what will bring humanity, at least the new generation, not the old… The old generation will die. In 75 years they will be all dead. Even those who are born today. So, that's good, I think, that humanity dies out and the new—those who are growing up now, growing up in a completely different kind of understanding of what can...

It’s natural.

Yes. But those, the grown up, the older generation are using it for negative purposes. And sometimes the younger generation is caught in it too. Because, I think in the United States and Russia it's the older generation. That Trump is mostly... OK, that is some young people caught also in it, but the majority is not with Trump, not with Putin, not with any of those, or ISIS, or whatever. I think it's still the old generation that perpetuates those religious—religious fanaticism. All those come from the older generation.

And education.

If all those who are older than 25 would die tomorrow I would just bless, “Oh, great. That's beautiful. Now we'll be somewhere else finally.”

So you think there is a lot of being stuck.

Yes, stuck. We are entrapped. There are so many traps. All this—the corporations. All the video. We are surrounded with traps of thinking. You know, we are changed, constantly attacked, and we cannot resist. We are caught in those nets. Yes. So, only that will save humanity.

The new generation.

Yes.

Of course one can say “Yes, yes, yes—well, look to some young people, and there in the South, you know, so many of those young people who voted for Trump. What do you want? How many young people enlist into ISIS? Huh? What are we saying?” No. But, they get caught into that. It's... Ok, like Hitler, not everybody in Germany believed really that you should kill Jews and be a Nazi and sieg heil. One can get caught into the fanaticism, into like we are weak, we can be persuaded and caught, like hypnotized—a certain variety of hypnotism that enters here. And they're caught in it. And they vote like their parents do. Unfortunately, that exists.

But do you feel like that's always the case? Or, do you think there are times when the younger people completely break away?

Yes, it always.... But, there are, we are, as of, let's say, 1945—with the creation of the United Nations—we are already, humanity is in a different thinking. Now, I think that was like—a point was made that now the world is one, humanity is one. Enough of this, you know, all of those separations and wars, and let's be one. But, we are not yet accepting that humanity has changed, that we are somewhere else now. And even, I hear now the politicians. Some say, “Oh, we don't need United Nations.” They want to go back before 1944. Back! They want to go back! But we are already somewhere else, you see. It's not the same as it was when we say, “Oh, that's how it always was.” It is that the parents always effected the younger generation. But, most of the parents of today are not thinking the same way as parents of before 1945. Humanity is somewhere else. Many of those parents who are 45 years old, let's say, they believe that the world is one, that we are one, that we don't need wars, we don't need all the—we don't want to deport Muslims, we don't. We are together, you see. But those who are older. There are still many. The majority of those are still caught before 1944, '45. But the majority of humanity, I think, is already...or, a good number... Just wait another ten or fifteen years. It will be a majority. And then the United Nations will have much more impact. We should, everybody should support the United Nations.

So we have to wait for a little while?

Well, we don't wait.

We don't wait.

We act.

Even in the face of everything being so static, and so many traps?

Yes, we have to resist the traps. By naming: “This is a trap!” By naming the devil when we already make a statement and we cross it out. And we resist... and we are somewhere else.

Yeah, so that's my political statement.

Or, we read Pythagoras. Or, we read the old 8th-century Chinese poetry that will tell us where to move. Or, we read Jacob Böhme, the shoemaker from the 16th-century. He will tell us what it's all about.

The mystic.

Poetry. We need more poetry.

More poetry.

Yeah. So, I said enough.