When Bruce Lee arrived on the set of his breakthrough film, The Big Boss (1971), he clashed immediately with his director over the action. A one-time child star who spent his adult life in Hollywood, Lee had none of the acrobatic Chinese opera training of the Hong Kong stuntmen, and had no interest in it, either. He saw film as a medium through which to express his philosophy of the martial arts, which involved liberating oneself from “rehearsed routines” and dispatching enemies with as few moves as possible. If you’re fighting a henchman too long, you’re clearly not a master. Does that make the fight scene too short? Send more henchmen.

After a week, the director was fired, and the rest was history. Of course, one reason Lee won that battle is because he was as great a showman as he was a fighter. We remember his pained mugging and cat-like battle cries; his swaggering body and restless eyes; his ability to toggle between stillness and fury, and to always hold traces of each within the other. Were he not a once-in-a-lifetime screen presence, his minimalist fighting style might have been a little boring. Both the breadth and limitations of the Little Dragon’s legacy can be felt in Spectacle Theater’s series “Milking the Dragon: The Golden Age of Bruceploitation,” which collects three highlights from the decade’s worth of rip-off movies that followed Lee’s death in 1973. It’s safe to say that none of them do justice to his philosophy or fighting style, but Lee’s impact is vast and multifaceted, and these tacky, wonderful movies tell us plenty about what he meant and means.

Several of the earliest Bruceploitation movies focused less on Lee’s life than his untimely death, which was both shocking (how could this happen to a guy in such good shape?) and sordid (he passed in the apartment of his mistress, with cannabis in his system). A Taiwanese stuntman named Ho Chung-tao, rechristened “Bruce Li,” starred in no less than five Lee biopics produced between 1974 and 1976, two of which focused heavily on Lee’s affair with actress Betty Ting Pei. He also appeared in a couple of conspiratorial films about Lee’s death, including Exit the Dragon, Enter the Tiger (1976), a sleazy treat screening this month at Spectacle. Exit the Dragon torques the plot of Fist of Fury (1972), with Bruce Lee as the dead master and Ho as a disciple who questions the official story. Soon he discovers that Lee’s mistress “Susie Young” has proof that Bruce died in a mob hit, and begins a one-man war against the Hong Kong underworld. Capably directed by veteran journeyman Lee Tso-nam, the action comes at a steady clip, and amateur historians will enjoy how the street-level production captures the Hong Kong of the day in all its bell-bottomed glory.

In interviews, Ho has recalled his shame at wearing the “Bruce Li” name, and his resentment toward the producers and distributors who wouldn’t let him shake it. Though he struggled to create a screen persona distinct from Lee’s, Ho did manage to shift away from being a strict copycat, eventually building a filmography whose high points (notably Dynamo, 1978; The Chinese Stuntman, 1982; and The Iron Dragon Strikes Back, 1979) compare favorably with Lee’s. None of this can be said of “Bruce Le” (real name: Wong Kin-lung), a former Shaw Brothers bit-player who became the most shameless of the clones. The posturing, the nose-thumbing, the squeals—if he failed to capture Lee’s charisma, he certainly chewed more scenery.

Produced cheaply and for undiscriminating international audiences, the “Bruce Le” movies play like a dim adolescent’s Bruce Lee fan fiction. This can often be a lot of fun, particularly in the case of The Clones of Bruce Lee (1980). The plot: shortly after his death, Bruce’s DNA is used to create three doppelgangers, all of whom look a bit like Bruce Lee, but not much like each other (Bruce Le is joined by prolific South Korean clone “Dragon Lee” and the lesser-known “Bruce Lai”). From there, one of the clones enters the movie industry with an unscrupulous producer who plans to kill him on camera, while the other clones encounter both an army of iron bronzemen and a beachful of topless women. By the end, the inciting gimmick is all but forgotten; like a lot of “Bruce Le” movies, this one feels like it may have been pieced together out of several unfinished, unrelated movies.

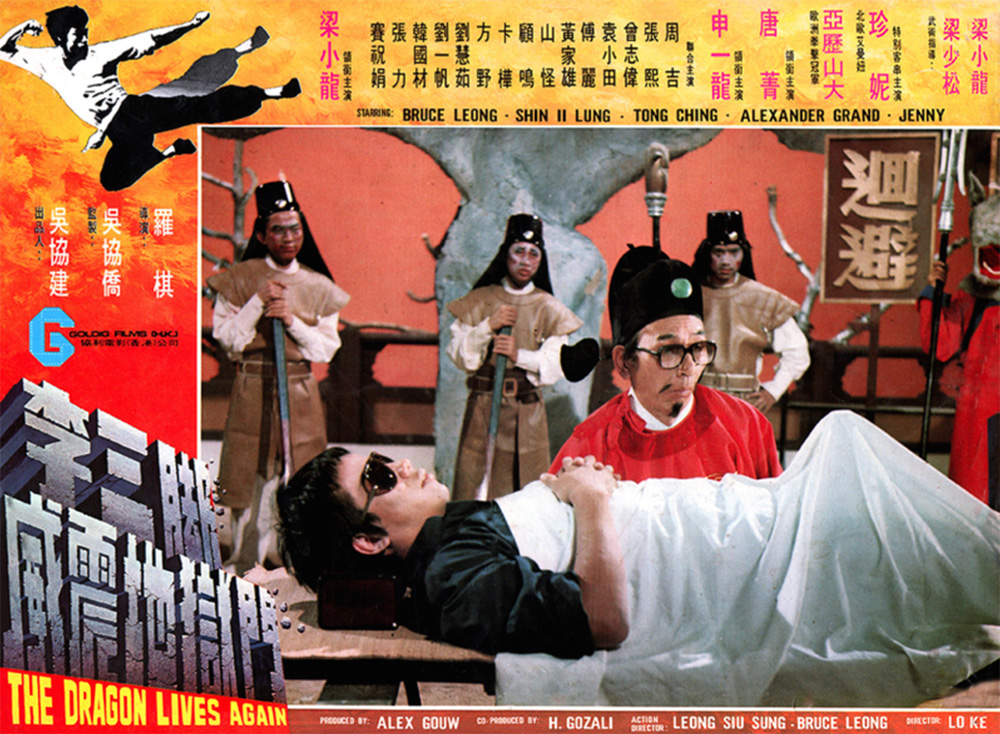

Bruce Le’s fight scenes tend to be sloppy and drawn-out—very different from the real Lee’s precision. As the Bruceploitation cycle went on, Lee became an increasingly disembodied signifier, and no film captures this more knowingly than The Dragon Lives Again (1977). Opening with the grammatically-challenged note, “Dedicated to millions who love Bruce Lee,” the film begins with Bruce Lee’s body on a slab, seemingly with an erection (a reference to a popular tabloid rumor that Lee died mid-coitus). The engorgement turns out to be a concealed nunchaku, and the movie is off and running. The story unfolds in the Underworld, a purgatorial state where Bruce has been banished. He quickly runs afoul of the vain Emperor and is made to battle a bevy of pop-culture icons: Dracula, James Bond, the Godfather, Zatoichi, Emmanuelle, the Exorcist, and “Clint Eastwood.” In Bruce’s corner are Kwai Chang Caine (from TV’s Kung Fu) and Popeye the Sailor (played by the future star Eric Tsang in a moving performance). This plot description fails to fully convey the movie’s vibe, which is goofy and relaxed, with a fine, tone-setting performance from “Bruce Leung” (actually Leung Siu-lung, who makes admirably little effort to look or act like the real thing). A readymade “Can you believe this exists?” item that is funny on purpose, The Dragon Lives Again is the crown jewel of Spectacle’s lineup.

Enter the Dragon preserved Bruce Lee in amber at the moment his artistry flowered. He wouldn’t live to see fashions change, but his clones would. The year after The Dragon Lives Again, Jackie Chan and Yuen Woo-ping’s Drunken Master perfected a style of acrobatic kung-fu comedy that was the polar opposite of Lee’s approach. In the 1980s, Lee’s protégé Chuck Norris would help whitewash the martial arts genre for English-speaking audiences. Meanwhile, over time, Lee transformed from star to legend, and when several rounds of discourse greeted Quentin Tarantino’s portrait of the martial artist as an arrogant young man in Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood (2019), it became clear that he now resides amongst the gods. His clones remain mere mortals, and for that reason, I kinda like them better.

“Milking the Dragon: The Golden Age of Bruceploitation” runs through the end of May at Spectacle Theater. Bruce Lee’s imitators are also the subject of a new documentary, Enter the Clones of Bruce, premiering June 10 at the Tribeca Film Festival.