How should history be performed? Perhaps not at all in narrative cinema, where historical figures and their deeds are shoehorned into satisfying dramatic packets that flatter contemporary sensibilities before worming their way into American high school curricula. The potency of images obscures the work of both consuming and fashioning the historical record. Controversies are ironed into a piety that unsurprisingly finds a happy home in conservative thought, which loves nothing more than a lost innocence. History is a series of arguments, but films have little room for caveats and certainly none for works cited pages beyond press junket interviews. Historical films, their grandeur unmatched, tend toward the authoritative incuriousness of American textbooks. Yet performance and historical navel-gazing are among the most human compulsions.

The question of properly staging history was central to the work of filmmaker Miklós Jancsó, who enjoyed significant international renown during the arthouse bonanza of the 1960s and 1970s before entering prolific obscurity in his native Hungary until his death in 2014. Considered by Béla Tarr to be the greatest of all Hungarian filmmakers, Jancsó never wavered in his antifascist critique of power dynamics, even after the international film community had largely ceased paying attention. His final work was a short contribution to the Tarr-produced anthology Magyarország 2011 (2012), which was conceived as a rebuke to Viktor Orbán’s suffocation of artistic expression in Hungarian media. Like most of the master’s 80-some credits, his swan song is nearly impossible for American audiences to see.

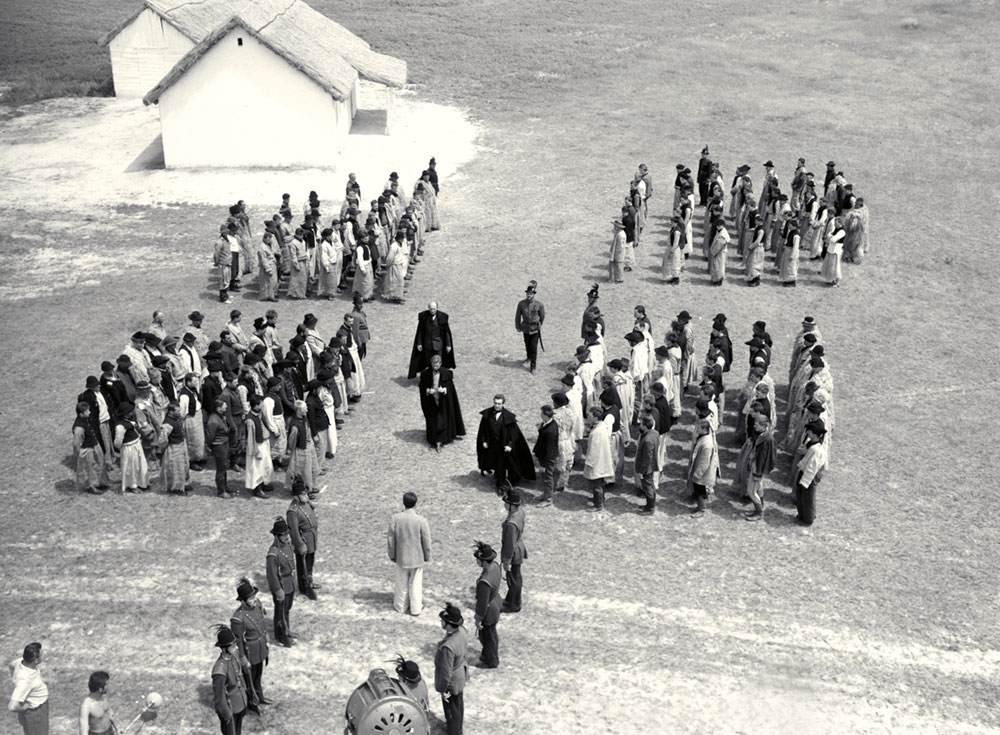

But this weekend Metrograph is offering a six-part reintroduction to Jancsó covering the period, 1965-1974, during which his name enjoyed the same breathless esteem as Godard, Antonioni and their fellow European modernists who still haunt rep houses like clockwork. Digitally restored by Hungary’s National Film Archive (no word yet on the Orban regime’s reaction), each of the six films—The Round-Up (1965), The Red and the White (1967), The Confrontation (1969), Winter Wind (1969), Red Psalm (1971), Electra, My Love (1974)—showcase Jancsó’s mastery of epic tracking shots wading through layers of intricate group choreography. Nearly a century of Hungarian history is represented and interrogated by this selection of films, from The Round-Up’s 1860s detention camp to the October Revolution in The Red and the White and then on to post-WWII student debates of The Confrontation. The series omits several works from the period, but the crash course should ignite enough interest to put the Monica Vitti-starring The Pacifist (1970) or the war drama My Way Home (1965), among others, on American screens.

His fourth feature, The Round-Up was Jancsó’s international breakthrough, screening at Cannes and introducing a large audience outside of Hungary to the sweeping tracking shots and insistent critique of power dynamics that he would refine for the next decade. The film takes place on the vast puszta, a grassland in Eastern Hungary that’s been farmed by various ethnic groups for millennia. A narrator informs us at the outset that after the industrial revolution reached Hungary in the mid-19th century, “The welfare of the bourgeoisie is all that matters.” Mounted representatives of this new class cast wide nets in their search for bandits/revolutionaries who survived a failed uprising against the Habsburgs in 1848. Entire villages worth of men have been interned in a camp where their captors subject them to sadistic interrogation games and absurd punishments.

Within single shots, the camera pans or tracks between individuals isolated by the guards for persecution and the larger collective huddled in the makeshift prison yard. Similarly, narrow wooden corridors open suddenly on to the endless puszta. The long takes accumulate familiarity with small cutouts of geography, only to disrupt our sense of space when a slight pan reveals new figures and landscapes that had been just beyond the frame for minutes. There are no wide shots of the camp, which grows amorphous in the imagination. The spatial fog is contrasted by repeated emphasis on the material textures of the structures: wood grain, dirt, fresh masonry.

The dance between the powerful and the oppressed never steadies. Circularity runs through all six films in the series. Circles, mostly made of bodies, collide, surround, break and absorb one another as power shifts between the masses and agents of control. The Round-Up’s guards escort prisoners through the camp’s mazes and back again, revisiting threats and deals for cooperation as they go. In one of the film’s most arresting images, the men are forced to wear hoods and follow a donkey wheel in a short circle for no discernable purpose other than degradation.

Jancsó’s encircled masses and long takes reached their apex with Red Psalm (1972) and Electra, My Love (1974, pictured at top). Featuring only a few dozen shots each, the films offer a nearly impenetrable array of historical symbols and folklore in which groups of singing, dancing and naked peasants lock arms in solidarity against tyrannical forces. The former concerns an 1890s farm strike while the later adapts ancient Greek mythology, but both provide blunt screeds against coercive power while bathing the eyes in unforgettable images. In Red Psalm there is again the dance of circles, as soldiers continuously surround collectivized farmers, who form their own rings of celebratory dance that outflank their oppressors. They read from Engels, disarm the soldiers, burn crucifixes and rewrite the Lord’s prayer to reflect their commitment to socialism, but they never stop dancing alongside Jancsó’s camera. In both films the obscurity of Hungarian folk symbols sits comfortably alongside clear-eyed polemics such as: “The leaders of the present social system will never relieve the distress of the working classes by their own will. We must organize ourselves so one day the organized workers can set their own power against the present autocratic system. Then it will be possible to make laws protecting the interests of the workers and ensuring the welfare of the people.” Amid Jancsó’s sumptuous pageants, history is reclaimed and engaged against the powerful.

Jonathan Rosenbaum called Jancsó a “lost continent” of cinema upon the filmmaker’s death in 2014. These restorations are hopefully a preliminary expedition on this terra incognita.

Miklós Jancsó x 6 runs today through Monday, January 17 at Metrograph. The films tour nationally before a spring disc/VOD release from Kino Lorber.