The highest compliment one can pay to a festival like Il Cinema Ritrovato, the world’s largest dedicated to restorations and repertory screenings, is that one often leaves it with more things on their “to watch” list than they had coming in. The “Restored and Rediscovered” series alone made up for roughly a third of the more than 350 titles programmed in the festival’s 39th edition. And this is before one considers the 14 other series, from retrospectives of individual filmmakers and actors, to thematic topics and anniversary screenings. Included this year were career retrospectives of the Italian jack-of-all-trades Luigi Comencini, the French feminist provocatrice Coline Serreau, the actress Katherine Hepburn, and the American director Lewis Milestone; tributes to Scandinavian noir and the prewar films of Mikio Naruse; and a series of musicals shot on small-gauge formats. And then there are the outdoor screenings every evening at the Piazza Maggiore, where a mix of locals and specialists alike gather to watch films ranging from actor-director Aldo Fabrizi’s Bologna-set comedy They Stole a Tram (1954), to Ramesh Sippy’s box-office hit Sholay (1975), to a live-orchestra presentation of Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925), newly restored this year for its 100th anniversary with some seven minutes of additional footage discovered since its last reconstruction in 2012.

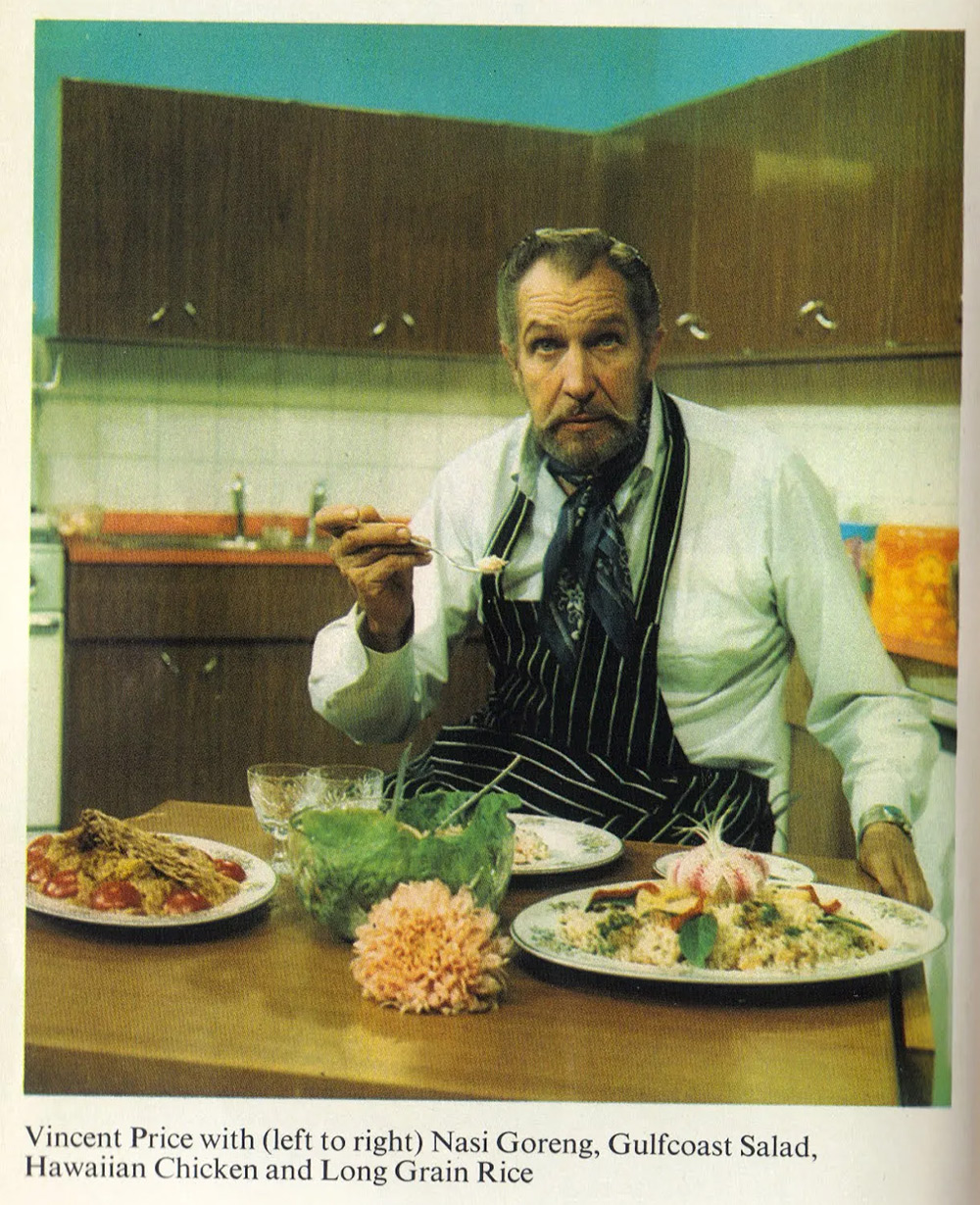

Facing a festival of this size, the most one can say is that they “sampled” it. On any given day, one can find themselves ping-ponging between eight different theaters to catch any number of delights: an early John Ford silent, recently rediscovered in Chile; a 1939 ethnographic short once described by Michelangelo Antonioni as the first work of neorealism; a documentary about the closing of the German concentration camps by the photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson; two episodes from a cooking show hosted by Vincent Price; first features by Jean Renoir, Alfred Hitchcock, and Ciro Durán; an anti-Nazi propaganda short by Polish experimental filmmakers Franciszka and Stefan Themerson, made while exiled in Britain; a Ukraine-set American WWII propaganda film starring a singing Dana Andrews; and the 4K restoration of Edward Yang’s Yi Yi (2000). Even after studying the program closely in the week leading up to the festival, I still found myself surprised to find certain films had flown under my radar. It was only while attending a screening of Jomí García Ascot’s On the Empty Balcony (1961), a striking film about a Spanish family exiled to Mexico during the Spanish Civil War, that I learned of at least two other Mexican films in the lineup restored by Filmoteca UNAM, including Leobardo López Arretche’s El grito (1968), a cine-tract of the student protests that took place in Mexico City in ‘68.

Both the size of the festival and the diversity of offerings within it makes each person’s experience fairly unique, and the variety of screenings allows for unexpected connections. Watching two films from 1933—Dorothy Arzner’s Christopher Strong and Milestone’s Hallelujah, I’m a Bum—within four hours of each other really visualized how diverse and experimental early sound cinema can be, both offering positive proof that the period was anything but stilted. It was fun to recognize many of the locations in Odessa made famous by Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925) in Aleksej Granovskij’s contemporaneous Jewish Luck (1925), also shot, albeit less creatively, by Eduard Tissé. And I was surprised in similar ways by Sumitra Peries’s Gehenu Lamai (1978) and Tang Shu Shuen’s The Arch (1968), both multi-generational portraits of women and both extremely dexterous in their use of a zoom lens.

One of my priorities each year is Cinemalibero, the annual series of the festival dedicated to Third World cinema programmed by Cecilia Cenciarelli. One can count on at least one of the festival’s real standout features to turn up there. (Previous years have included the premieres of new restorations of Heiny Srour’s Leila and the Wolves, Bahran Beyzaie’s The Stranger and the Fog, and Sarah Maldoror’s Sambizanga.) Some highlights this year included Dariush Mehrjui’s The Postman (1974), a retelling of Alban Berg’s Wozzeck adapted to the class politics in pre-revolutionary Iran; Bahram Beyzaie’s amazing The Journey (1972), an existentialist short film produced for the children’s cultural institute Kanoon; Al Ôrs (1971), a drama performed by the experimental theatre troupe Collectif Nouveau Théâtre de Tunis; and The Razor’s Edge (1985), also known as A Suspended Life, the first fiction film directed by the great Lebanese documentarian Jocelyne Saab.

The opening film of this year’s Cinemalibero, Peries’s Gehenu Lamai, was one of the first films I saw at the festival and remained my favorite to the end. Peries, who died in early 2023 at the age of 87, held the distinction of being the first woman filmmaker in Sri Lanka. Like another film in Cinemalibero, Flora Gomes’s Those Whom Death Refused (1988), Peries’s film depicts the struggles of women in post-revolutionary society who face both colonial and gender oppression. But Peries’s shooting style is a far cry from the social realist approach more typical of the period. Nicknamed “the Poetess of Sinhala cinema,” she composes scenes in extremely unorthodox ways, sometimes shooting through mirrors and other times reframing the image by zooming in and out. Like Josef von Sternberg, Max Ophuls, or Yoshishige Yoshida—to name three other decadent visual stylists—she will often place the camera in front of objects blocking characters in the frame, prioritizing a visual suppleness over narrative clarity. At times, the experimental approach to the film reminded me of Satyajit Ray’s new-wave period, and catching the new restoration of his Days and Nights in the Forest (1969) reinforced this comparison. But Gehenu Lamai is even more daring, and one hopes that the restoration of this film will allow her following nine films to receive similar treatment.

On the other side of town, I had a chance to see three of the four films directed by Willi Forst in the series, “Masks and Music,” curated by the critic Lukas Foerster. Foerster’s previous programs of ‘30s German-language comedies have been some of the best discoveries for me in recent editions of Il Cinema Ritrovato. I’m not alone in this opinion. No less an authority than the French film critic and historian Bernard Eisenschitz recently commented, in a conversation reproduced in the film magazine Outskirts, that these series “completely changed” his opinion of early German sound comedy. One of the major stars to emerge from these earlier programs was Forst, a charismatic singer and romantic lead who might be likened within German-language cinema to what Maurice Chevalier was to American cinema and Vittorio De Sica to Italian cinema. And like De Sica, Forst was quick to translate this popularity into a career behind the camera. He quickly became one of the more popular filmmakers in Europe, enough that scenes from his debut feature, Gently My Heart Entreats (1933)—a biopic about the Austrian composer Franz Schubert—were reused in Yasujiro Ozu’s The Only Son (1936).

Together with Ophuls, whose debut feature The Company in Love (1932) also played in the lineup, Forst’s films helped define Viennese cinema, distinguished both by a sophisticated tone and technical deftness. His finest film, the operetta Maskerade (1934), helped build his reputation for light, refined comedy with which he would be associated for the rest of his career. Allotria (1936), a riotous screwball following the template of Ernst Lubitsch’s One Hour With You (1932), plays like an anthology of American comedy—not just in the more suggestive Lubitschian moments, but also in others which borrow from Astaire-Rogers musicals like Flying Down to Rio (1933). Both films also benefit enormously from performances by the effortlessly suave Anton Walbrook, prefiguring his late-career roles for the Archers in The Red Shoes (1948) and Ophuls in La ronde (1950).

Writing about Forst in English is scant, but by happy coincidence, two articles on Forst by Stefan Grissemann were published late last year in the two-issue dossier on Austrian cinema by the London-based magazine YES&NO. These articles are a helpful English-language primer on Forst’s career, though they also put pressure on the claim that Forst’s films—among the most successful German films made under Nazi rule—are merely “hiding places” from the horrors of Nazism. It may be true that Forst was generally disliked by Goebbels, but whether this absolves him of accusations of collaboration is certainly debatable. Among other things, he worked with known Nazi supporters: the cameraman on Allotria, Werner Bohne, also worked for Leni Riefenstahl on Triumph of the Will (1935). The case of Willi Forst is a complex one, and the four films included in this year’s series, all made before the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938, only offer a partial presentation of his career. Hopefully, a second part to this series in a future edition featuring his later films may help shed more light.